Music is the universal language

“Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace to those on whom his favor rests.” - Luke 2:14

Premier Guitar

Learning to Write Music: One Word That Changed Everything

As a young musician, I always knew I wanted to be a recording artist. I started to notice that my mentor, Laurence Cottle, was often leading his own bands more than playing sideman gigs. He was the best example of a bass player writing original music and fronting a band that I could’ve asked for.

There was just one tiny problem: 30 years ago, I had no idea how to write music. In fact, I didn’t even know where to begin learning composition or how to turn ideas into recordings or live performances.

Luckily, around 1994 or ’95, Laurence took me to a show at London’s Jazz Cafe. He was playing with Bandzilla, an all-star big band led by American arranger and producer Richard Niles. I had no clue that a 30-second introduction to Richard would turn into a second mentorship—one that eventually helped me move to the U.S. and become a full-time musician.

There’s something about the positivity of American musicians that always fascinated me, and Richard was, and still is, one of those people who loves to say yes. He’s endlessly curious about new talent and always enthusiastic about helping you succeed.

He wanted to hear me play, and I wanted to learn everything he knew—chord voicings, arranging, producing, orchestration, composing—all the knowledge that comes from working with artists like Paul McCartney, James Brown, Pat Metheny, and Depeche Mode.

Picture me at 16 or 17, knowing the heavyweight status of this guy, being invited into the studio to hang out and make music. I had to remind myself not to let my jaw hit the floor when the wildest stories were told. And he had all the keys to the castle: everything I craved to learn about how to put pen to paper, audio to tape, and people in seats at live shows.

But the one thing that stuck with me most from that time—and what I want to share with you—is Richard’s insistence on the importance of form.

Now imagine me, a total rookie, saying something like, “I can’t write music,” and Richard jumping in with: “Just take care of the form, and the rest will follow.”

He knew I had a couple of strengths, one of them being listening. I listened to music every second I wasn’t playing it. I wore out records. I chewed up cassette tapes from overuse. I never said no to something new.

That’s when Richard explained that I probably already had a solid grasp of melodic and harmonic ideas, simply from absorbing music so deeply. What I hadn’t paid enough attention to yet was form.

He had me name a random song I liked. I picked “The Chosen” from the Yellowjackets’ album Dreamland. The album had just come out, and I was listening to it every day.

He told me to transcribe the form—not the notes or chords, just the number of bars in each section. Then I had to label them: “Intro,” “A-Section,” “B-Section,” “Bridge”—just the bare bones of the structure.

And by doing that, a roadmap came into focus almost immediately.

I already had licks and lines I loved to play. I had chords I was obsessed with. I’d been fascinated by certain classical passages and often wondered how to incorporate them into my own music.

When Richard said, “Now you have somewhere to put all your ideas. Follow the form, and the song will start to make sense,” he was absolutely right.

Of course, it was rough at first. None of those early compositions ever made it onto an album. But by identifying the forms of songs I loved, I expanded my options. I started recognizing patterns. I began writing within those frameworks. I started to better understand form as a bassist too, which helped massively when gigging.

And over time, from that one simple idea, I created my own forms, my own compositions, and eventually, my own career as an artist.

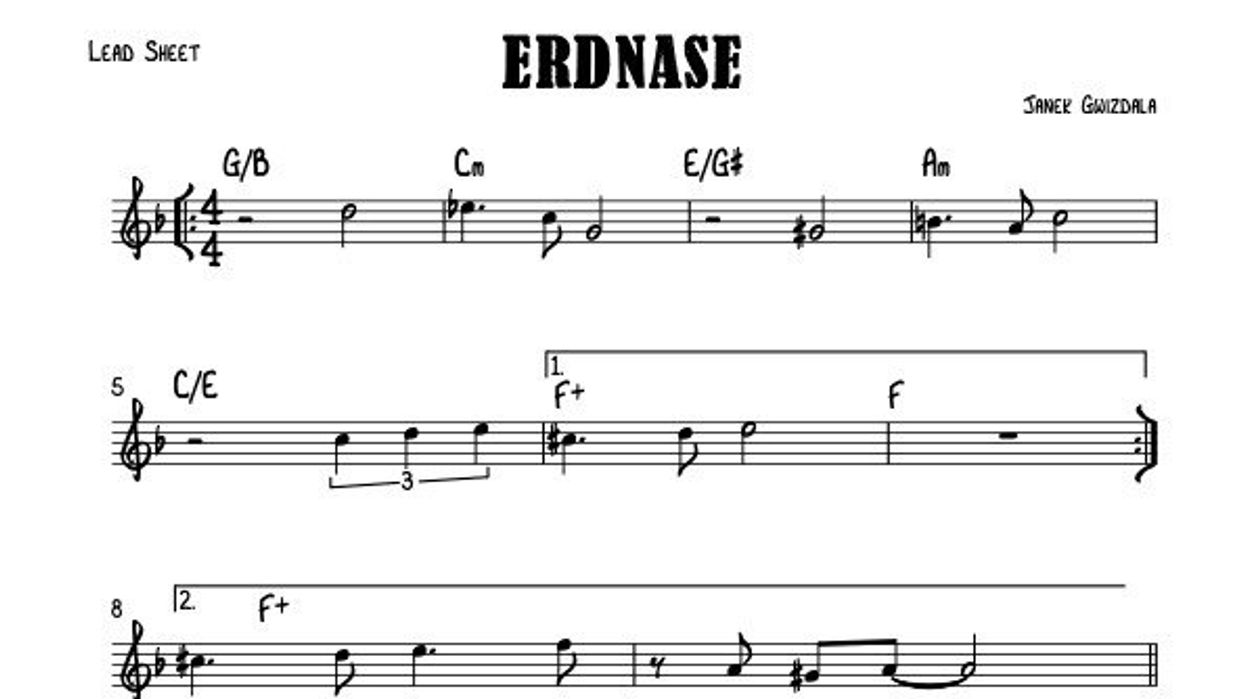

I’ve included a song of mine for this piece. It’s in AAB form—but with an unusual bar structure: 7–7–15. I encourage you to steal that form and see what you can create. It might just be the start of your own journey into writing music.

Question of the Month: The Amps We Can’t Live Without

Question: What’s your No. 1 amp and why do you play it?

Guest Picker

Luther Dickinson

A: My main amp on the road is my signature Category 5 LD100 (or LD50 in a small room). Don Ritter and Barry Dickson of Category 5 and I designed this amp similar to a 100-watt Marshall plexi, but with nice subtle spring reverb and a groovy tremolo that goes from very slow to very fast with a foot pedal controlling the speed.

- YouTube

Obsession: Live Prince concert footage does not count because that’s constant, but I’m thrilled by Tolgahan Çoğulu and his microtonal guitar YouTube page! As a slide player I’m familiar, even intimate, with some of the microtones they utilize with these amazing guitars with movable modular frets, and thus I love his music, approach, and this scene (including King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard).

READER OF THE MONTHSteve Rempis

A: Having recently embraced doom metal in a big way, I started on a quest to find the perfect amp for getting a distinctive tone and taking fuzz pedals. After trying all the usual suspects, I stumbled upon a circa 1972 (just like me) Kustom Hustler 4x10 combo. This amp gives me what I consider to be my ideal doom tone, especially when the bright switch is engaged (contrary to conventional wisdom). I pair the Kustom with a Roland JC-40, which handles all my time-based effects. My rig looks and sounds unique, and most definitely dooms!

Obsession: My current obsession is parallel fuzzes. When looking for my perfect fuzz sound, I found that I had three pedals (a Pro Co RAT 2, a Rowin Frenzy, and a Keeley Suns) that didn't get me what I wanted in isolation, but each did great things as part of my tone spectrum. The obvious solution? Run all three! A little internet research led me to the Electro-Harmonix Tri Parallel Mixer pedal, which allowed me to run all three pedals together as separate signals which were then combined at the output. No “stacking” required. I now have a “best of all worlds” fuzz sound that brings a big grin to my face every time I plug in.

Charles SaufleyGear Editor

A: My 1964 Fender Tremolux is my first amp and it’s certainly the last one I would ever sell. For my purposes, the Tremolux, with its 30 watts and tube rectifier, deftly splits the difference between a tweed Fender’s squish and growl and a black panel’s clarity and immediacy—a nice lane for a lad that counts circa-’69 Crazy Horse, early-’60s South Bay surf, and Mod-era Pete Townshend as tone ideals. With a Fender Reverb unit and an Echoplex out front, it is pure joy.

Obsession: Making space in mono mixes. It’s a great workout for the ears, a cure for option fatigue, and reinforces and encourages smart arrangement decisions. But as an individual that marvels at the potency, punch, and sometimes spooky ambience heard in mono records, it’s fun chasing the magic that lurks in those slabs of wax.

A: My Dr. Z Maz 18 Junior 2x10 combo has been my dream machine for about 11 years now. It’s a Mark I model, with reverb. A few months back, it wasn’t keeping up with my band at a show, so I started looking around for a used amp in the 50-watt range. I went through a few heads and cabinets only to end up back at my Z, which I paired with a Fryette PS-2 to raise its wattage to 50. Maybe 11 years of Z has just cemented my amp’s frequency range in my brain, but whatever the case, it just feels like home.

Obsession: Finding the perfect balance between chime, depth, and aggression. I favor single-coil tones that have a lot of pluck and definition, but striking the right harmony with top-end clarity and thick, characterful distortion is tricky. Blue Colander’s Crooked Axis, a massively expanded take on the Colorsound Power Boost, has been getting me there the past few months. But I have started to wonder: Can I depend on my ears to dial in the sound I want, or have I lost enough high frequencies in my hearing that I’m not a reliable tone sculptor? Overthinkers anonymous, unite.

The Funky Bass Continuum: Bootsy Collins and MonoNeon in Conversation

The word “parallel” is easy to use to describe bass luminaries Bootsy Collins and MonoNeon. Both are remarkably distinctive, not only in their playing style but in their fashion, and they both exist on the leading edge of musical and technological trends. And both innovators have what seems to be everything: signature model instruments and effects, adoring fans across the globe, and the biggest and most important attribute of all, humility.

The career paths of these two have been eerily similar, albeit decades apart. Collins, who is 73, electrified the club scene in Cincinnati, eventually being handpicked by James Brown to join his band. Prince caught wind of MonoNeon, who is 34, via his clips online, and soon the young bassist was standing next to Mr. Nelson at Paisley Park, bringing new energy to the Purple One.

Both have just released new records. MonoNeon’s You Had Your Chance … Bad Attitude blends funk and soul with dashes of heartbreak and humor, adding to his extensive list of releases. Bootsy has dropped his Album of the Year #1 Funkateer with a fury, collaborating with Snoop Dogg, Fantaazma, Eurythmics’ Dave Stewart, and Ice Cube to blend classic funk with modern grooves.

In our hour-long bass conversation, we talked about church, family, and finding your voice in the world, and I was genuinely surprised to hear the tech-savvy approach of the “old guard” Bootsy and the “old soul” approach of the social media influencer MonoNeon.

Bootsy Collins: What year did we meet, and you did the bass thing on my record?

MonoNeon: Two-thousand-sixteen. That was with [drummer] John Blackwell.

Collins: That’s right. That’s when we really got together in person and started hooking up. I checked out Mono on Twitter at the time, and he had such a style and he used the instrument not just as a bass; he took it and communicated with it, showing people that whatever you are saying you can speak through music. It was pretty incredible, because in my day, coming up, that was like a breath of fresh air.

Bringing musicality to everyday life was that extra step.

Collins: Then the other step was that, you know, he has his grandma on. Kids don’t do that. They want to get away from their parents, and here’s this young cat coming up, sitting with grandma, going to church. So I had to meet this cat.

You bring up church—did you guys play in church?

MonoNeon: Oh yeah. I grew up in church. Grandma used to take me to a Baptist church in Memphis. I started playing there at age 9. It was intimidating. There were a lot of great musicians there.

Collins: There’s nothing like it. Maybe if we hadn’t started there, we wouldn’t be where we are now. That’s the “one.” You start right there, then grow. You can be away for a minute, but that feeling never leaves you. If you don’t have church, though, you don’t know how far is too far. That’s one side; then there’s another side, the Holy Spirit, where you aren’t acting, you’re just being yourself and playing and letting this spirit take over. I know Mono went through that sort of vibe with Prince, too.

Walk me through when Prince brought in a new track or idea.

MonoNeon: I always just waited on Prince to tell me what to do. I would do my thing on it until he told me “don’t do that.” He always let me be myself.

You mentioned John Blackwell earlier. What a force. Let’s talk about drummers for a minute. What do we like in drummers?

MonoNeon: Well, for me, the drummer has to have a lot of personality. He has to have great sensibility and just be fearless. I really don’t care about a lot of chops.

Collins: With me, my heroes were Clyde Stubblefield and Jabo Starks. And I never could dream of getting the opportunity to play with them. When they came to record at King Records here in Cincinnati, my dream was to at least meet them. I wasn’t even thinking about getting a chance to play with them. It just happened to turn into a relationship once James Brown hired us [Bootsy and his brother, guitarist Catfish Collins], which was unreal at the time. Standing in between those two … Clyde was fire. He was just fire. And Jabo was just the watery, jazzy, swinging-type drummer. A lot of people don't know the difference in their styles. You know, they just say “James Brown drummers,” but James would use either Jabo or Clyde to record, depending on the style of the song. James knew.

Tell me more about James.

Collins: The way he treated me and my brother was, “Y’all go ahead and do your thing,” much like Prince with Mono. It was more about our energy coming into the studio rather than his. James would tell us parts in advance, and he was looking for that young energy. James would let us go into the studio before he got there, and we would be in the room grooving and James would come in, like, “Keep it going, keep it going, start the tape.” He’d start the tape up, he’d run out there to the mic and just start yapping—ha!

Where did you track with James?

Collins: We recorded in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, and Criteria down in Miami. King Records here in Cincinnati is the main one. We’re actually in the process of revitalizing the room and getting it up and cracking again. We think there is a lot we can do for the music and the historical side of the scene here.

Speaking of the scene, Mono, you are in Memphis. You grew up with the Stax Records location right down the road and Beale Street not too far away. Your dad, Duane Thomas, is a bass player with some big credits as well. What records were on the family turntable when you were little?

MonoNeon: Probably some stuff my dad played on. My dad used to play with Denise LaSalle and Mavis and Pop Staples, so I was listening to all that. My dad also played with the Bar-Kays in the late ’80s. I had music from church and the records my grandma was playing as well—blues like Jay Blackfoot and Johnnie Taylor. That’s why I’ve got an old soul now, because I was hearing all that shit.

What was the scene in Cincinnati like in the late ’60s and early ’70s?

Collins: Well, at one time it was a great, great scene because you had clubs everywhere and all the bands were working. We’d go and sit in with each other. Roger Troutman, Ohio players, Slade, all these mugs were just working in clubs. And it was an every-night situation. The scene was beaming with clubs and places to go and places to do things so you can show your talent. We didn’t have the computer thing, online and all that, so you actually had to be somewhere to show what you got. We used to walk in clubs and have our instruments out. When you walk in like that, you kind of demanding, like, “We coming to take your gig,” you know? We [Bootsy and Catfish] always brought it. So, we had the reputation going. Then everybody kind of knew, oh, them Collins, them Muppets. That’s why James was looking for us.

You both have new records. Tell me about the process of making them.

MonoNeon: It’s really just trial and error for me. I sit down at the keyboard and try to figure out harmonies that feel like me. It’s seeing what works or not. I try leaving that space open for whatever comes.

How do you map it out? Is it bass parts first then everything else? Do you chart it out as you go?

MonoNeon: I don’t chart anything out. I just open up my DAW—Logic—and get on the keyboard and figure out some shit. I make a beat first, usually, especially when I’m working by myself. The guy I work with in L.A., David Nathan, we write songs together, and he’s a great songwriter and producer. So when it comes to songwriting, it’s easier to narrow ideas when I work with him. He’s like a brother to me. So, I trust him with my vision and what we want to do. But since I’m so quirky, he knows my quirks, so he’s able to flesh it out. I am definitely learning more about songwriting being around Davey as well.

Bootsy, you have moved into more of a producer role for your new record and have some heavy guests. How do you adjust for each one?

Collins: I guess for each song the process really is different, and they come to you differently as well. Back in the day when I was coming through with George Clinton, Parliament-Funkadelic, we got a chance to just vibe a track out, because we always had the band with us. Today is totally different. I might say, “Mono, I’m gonna send you a track and check it out and see if you hear anything on it.” Then he’ll get back and say, “No, I ain’t feeling it.”

MonoNeon: C’mon!

Collins: I mean, he ain’t done that yet. Mono always comes up with it, sends it back, so I am always learning. I think with this new record, it gave me an opportunity to learn even more. For example, a few of the songs I did with Dave Stewart, he’s playing acoustic guitar, because I wanted to do some real songs—ones with less groove jams and more structure. That’s something I’ve never done. I’ve always played experimental stuff that comes off of my head. I’ll jam with this groove, or I tell a band what to play, and here’s the tempo. But on this record, each song is different. If I’m going to use a rapper on a song, I’ll write something in that rapper’s style. I probably will never be exact to the genre, and I ain’t trying to be. That’s the good part about it. For me, you know, it’s always wanting to do something different and new. I wanna keep learning different things from different cats, and I feel like we are transmitters and receivers. And if you don’t shut up, you’ll never receive.

MonoNeon: I guess we got good ears and we just hear everything. I don’t consider myself a producer; I just do stuff.

Collins: That’s the attitude that I liked about Mono even before I knew him. You can just tell certain cats got a certain vibe that you already know that you’re gonna gel with them, and that’s why we are closer than we even know. Bass players become producers. We can become anything, you know? But the main thing is we use instruments to communicate. And instruments ain’t just what I play, it’s what I wear—my fashion is an instrument, my glasses are an instrument, you know? My tone, I mean, everything that a bass player uses, is a part of him. We can’t track that stuff; it’s just us.

Since you mentioned tone and this is a guitar magazine, what are your two desert island effects pedals?

MonoNeon: Ooooh, I guess my Whammy pedal and my Fart pedal.

Collins: For me it’s my Mu-Tron and the Big Muff. That’s what I started with. If I can sneak in a third, it would be a Morley wah with the fuzz.

Mono, when did you jump into effects?

MonoNeon: Kinda early on, but I didn’t really apply it to anything. My use of the Whammy pedal came from being around Prince. I was just watching how he was stepping on it. He had so much swag. I wasn’t really listening to it, I was really watching how he was using it. I just started applying it to what I was doing and cultivating it.

Collins: That became his Mu-Tron. That became a great move.

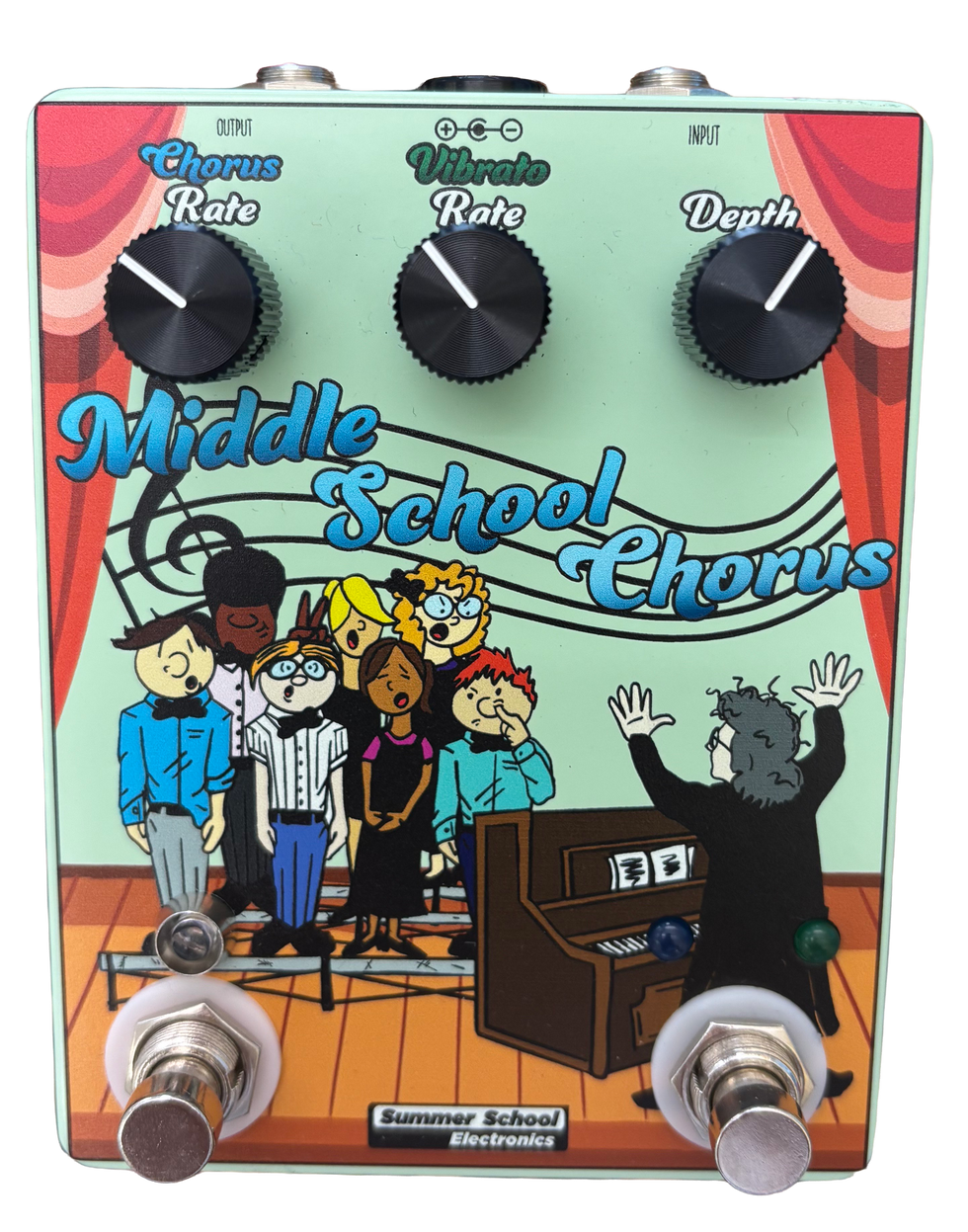

Summer School Electronics Announces Middle School Chorus

Summer School Electronics Middle School Chorus is a modern take on an 80’s classic.

The Middle School Chorus is a unique dive into modulation that saves pedalboard space and opens a world of sonic options. It combines both a chorus and vibrato effect into one stompbox, allowing the effects to be changed with the tap of a foot. This pedal has a wide range of modulation, from classic 80’s chorus-tones to wet, modern guitar sounds. When the blue light is on, the pedal is in Chorus-mode and can be adjusted by the Chorus Rate and Depth knobs. When the green light is on, the clean signal is omitted and the pedal is in Vibrato-mode and can be adjusted by the Vibrato Rate and Depth knobs.

Each pedal offers the following features:

• Separate Chorus and Vibrato Rate controls with a shared Depth control

• Footswitchable Chorus/Vibrato feature

• Hand Built in Syracuse, NY

• Lifetime Warranty

• 9-volt operation and standard DC input

The Middle School Chorus is available at Summer School Electronics dealers, at a street price of $199.99 as well as online at summerschoolelectronics.com.

Embracing the Great Unknown (Artists)

I recently watched a documentary on Nashville’s songwriting culture called It All Begins with a Song, and while it was an occasionally insightful and touching look at the tunesmithing industry, it omitted an important part of Music City’s creative community: the writers who fly under the mainstream's radar, and yet craft equally—if not more—satisfying numbers that hit deep emotional notes and tell profound human stories.

I get it. More viewers would like to watch how the songs they’ve heard were built than songs performed by artists who’ve not, for a lack of luck, financial support, or other business machinations, reached their ears. And yet, I felt the film missed an opportunity to enlighten people to a different kind of Nashville songwriter—a breed of artist less slick in, perhaps, the writing of Top 40 hooks, but sometimes more attuned to the rawness and complexity of real human experience. Writers who have the ability to capture humor, sadness, and life without flounced dressing. I’m thinking of artists like Buddy Miller, Kevin Gordon, Jon Byrd, Tim Carroll, and even Emmylou Harris—the latter a cross-generational bridge with the ability to create a beautiful latticework of words and music with her lyrical skill and unmistakable voice. (Note: Listen to Gordon’s “Colfax,” for example, and you’ll enjoy one of the most complex-yet-accessible stories about adolescence, small-town America, and race put to song.)

My point is this: When it comes to every aspect of the music you love, try to dig deeper. If you love guitar, and I know you do, don’t stop with Jeff Beck, Carlos Santana, Josh Homme, or Jack White. Find out about the outliers like Sonny Sharrock and Yvette Young and Stan Lassiter, or, if you dig blues, Junior Kimbrough. They are all uniquely and brilliantly themselves. And Tom Waits is the rare example of an outsider songwriter who has penetrated the mainstream, and a damn fine one.

“There are great artists flying just under the widescreen radar everywhere that music is played and stories are told.”

I’ve chased artists like this, and the songs and sounds they make, for my adult life. If I had to blame it on anyone, it would be Johnny Cash, whose unadorned music and poetry, punctuated with surprising vocal approximations of train whistles and shouts of “sooey,” spun my head around and opened my ears to the world when I was a child. (Cash was, perhaps, the ultimate outsider insider.) And because of this pursuit, and my decision to become a music journalist as well as a player, I’ve been able to speak with and even be befriended by quite a few of them. Their stories, whether in words or sounds, have profoundly shaped my perspective, character, and creativity. They influenced me to become and remain a storyteller, one way or another. Heck, some, and especially the late Mighty Sam McClain, the greatest soul singer you’ve probably never heard, even became my chosen family. In Sam’s case, a second and better father, whose voice echoed between the Earth and the stars. (Listen to his interpretation of Carlene Carter’s “Too Proud” for a jolt of scarred honesty, then explore his catalog.) The same with R.L. Burnside, who shaped my thinking as a guitarist and a human in ways I’d not realized until they were ingrained.

There are great artists flying just under the widescreen radar everywhere that music is played and stories are told. It just takes a little more effort to seek them out. Chances are, if you choose to speak with one of them after a performance or even through social media, you might make a connection. It could be a one-off exchange or it could be a new friendship, because life has a way of taking you down unforeseen roads if you are willing to take the first step onto them.

You might even be one of these artists yourself. If you are, you have my respect for striving forward, in search of the essence, the expression that helps the world fall into place for you and those for whom you record and perform. You may be underacknowledged but you are doing essential work. And you understand that it truly can begin with a song or a sound.

4 Black Sabbath Riffs That Inspired These Guitarists

In this video, some of your favorite players—Marty Friedman, Jared James Nichols, Steve Reis, and Nate Garrett—share personal stories that go back to the beginning of their guitar journeys when Black Sabbath riffs constructed their musical foundation.

Novo Voltur B6 Review

Nashville boutique guitar brand Novo was founded by Dennis Fano, of Fano Guitars fame, back in 2014. The two brands speak in similar design language and philosophy for obvious reasons, and Novo guitars have a style all their own. But like the first Fanos built by Dennis himself, Novo body shapes, finish schemes, and the feel of the instruments are prevailingly shaped by early and mid-’60s influences. Naturally these attributes shine when mated to the very Bass VI-like Voltur B6.

Origins of the Beast

A 6-string bass, unlike a baritone, is tuned exactly like a guitar, E to E—just an octave lower on a much longer scale. It’s likely the very first instrument built in this configuration was Danelectro’s UB-2 in 1956. But the famous evolution of the 6-string bass concept was introduced by Fender five years later, in 1961, and named the Bass VI. The Bass VI was never a common instrument, but it was, alongside the Danelectro, the choice for session players chasing the tic-tac sound, which mixes the percussive pick attack from a guitar and an upright bass. Six-string basses are all over genuinely classic tunes: “I Fall to Pieces” by Patsy Cline, “Wichita Lineman” by Glenn Campbell, and probably Elvis Presley’s “Jailhouse Rock,” which in 1957 became the first No. 1 hit in the U.S. believed to feature the 6-string bass. The Bass VI also turned up in the hands of artists like the Cure and Jack Bruce of Cream, and most famously was sometimes cradled by George Harrison and John Lennon while Paul McCartney tended to keyboards.

“It is really nice to see a manufacturer spend the time to develop such a refined take on the 6-string bass—premium price or not.”

For all the high-profile users and applications, Bass VI-type instruments like the Voltur B6 aren’t something too many manufacturers offer, and you see few in mainstream music. So, I was a bit surprised when my editor told me I would have the pleasure of reviewing one, and especially pleased it would come from such a renowned builder.

Luxury Accommodations

The Voltur B6 wows from minute one. It’s very stylish and well-made. And it is really nice to see a manufacturer spend the time to develop such a refined take on the 6-string bass—premium price or not. The finish is beautiful. Our review B6 came in a bold and attractive copper, but vintage-inspired paint jobs including Mary Kaye white, a very Gretsch-like nicotine blonde, a Silvertone-influenced starry night, and more are also available. The bass comes with three custom pickups by Lollar called Novo Gold Foils, which are visually distinctive for their almost industrial take on the vintage gold-foil design. Along with controls for volume and tone there are three very Bass VI-like switches for selecting different pickup combinations. Another striking design feature is the pairing of a Mastery M1 bridge with a Mastery NV vibrato with a lightning bolt arm that echoes the design themes in the pickup covers. The very comfortable 30" scale is spanned with a custom set of .026 -.095 strings by Stringjoy. I felt instantly at home.

It’s a Bass, It’s a Guitar, It’s…

When I grabbed the Voltur B6, the bass player side of my brain told me instantly to utilize the chordal possibilities of the instrument, largely because as a gigging bassist I don’t get to explore that technique as much. Playing a simple arpeggiated pattern, the notes rang out clearly like a guitar, but with the punch and authority of a bass (clip 1). The action of the test instrument was ever so slightly high for my liking, but I believe that contributes to the punch in each note. As a massive fan of the single-note signature lines normally played on a baritone guitar, I wanted to try that type of treatment on a melody line played very close to the bridge, for a skinnier, almost surf-like tone. The tone that came out of the Voltur 6 with the bridge pickup had an antique glow and a touch of garage attitude (clip 2). I desperately wanted to play more with this approach, but I was also eager to give the Novo the tic-tac treatment (clip 3). I recorded a bass line using a hollowbody short-scale bass and rolled off all the highs in order to better hear and feel the unique pick attack from the Voltur B6 when I doubled it. The result was a sound all its own—tubby, but warm and certain to sit prominently in a mix.

The Verdict

For an instrument that could be considered nichey, the Novo Voltur B6 is ultra-versatile. The three pickups offer significantly different tones—all of which have many possible uses. It’s addictive, utilitarian, and opens up many unique musical paths. And after living with this instrument for a while, I’m captivated by the idea of getting one for studio use. Novo’s Voltur B6 definitely comes with a boutique-builder price at $4,499. But the bespoke quality you sense playing up and down the neck, or just looking the instrument over, is undeniable. For any bass player or guitarist interested in a tool that can transport you beyond the box, the Novo Vultur B6 could lead to unexpected treasures.

Crazy Tube Circuits Releases Mirage

Mirage is a dual reverb workstation that goes far beyond traditional stomp box boundaries. Built around two fully independent engines - R1 and R2 - Mirage offers studio-grade processing, intuitive controls, and a remarkably flexible layout that appeals equally to sound designers, gigging musicians, and ambient explorers. Whether you're stacking two reverbs for depth, splitting engines across stereo channels, or dynamically morphing textures live, Mirage is built to perform.

Each engine can load one of 16 distinct reverb algorithms, organized into two banks. The Outer Bank focuses on natural, familiar reverbs: Plate, Spring, Cathedral, Room, Gated, and even the mythical Inchindown oil tank impulse (the longest recorded reverb in nature) - ideal for players looking to recreate spaces found in vintage recordings or real-world acoustics. The Inner Bank unleashes modern, ambient-driven effects: shimmer in various configurations (up, down octaves, blended, pitch-shi ed), modulation and echo based reverbs and infinite trails with the twist of a knob.

Each reverb engine has four dedicated knobs: Mix, Volume, Swell, and Excite. Swell typically controls decay or size, but some algorithms use it creatively - like gating time or freeze triggering. Excite is context-sensitive and adapts per algorithm: from shimmer balance to modulation depth, octave volume, or tone shaping. A Shi Push Switch toggles between the two algorithm banks, while a Voice Selector chooses the algorithm for each engine - no menu diving, just hands-on, instant access.

Routing is one of Mirage’s standout features. With series routing, you can stack the two reverb engines for massive atmospheric depth or use each engine independently for 2 mono reverb presets - engaging either footswitch as needed. Want to insert another pedal between the two engines? The SEND/RETURN loop between R1 and R2 is perfect for adding modulation, delay, filters, or even distortion/fuzz pedals for expanded textures.

Choose stereo or separate routing to process L and R channels independently, assigning distinct reverbs to each - or dial in slight differences on the same algorithm to widen the stereo image. You can even run two completely independent mono setups, each with its own activation footswitch. This is especially handy for one acoustic and one electric guitar setups, dual mono synth setups or setups using an external looper or switcher system. There’s also a Mono In/Stereo Out (MISO) mode, ideal for mono guitars, synths, or front-of-house reverb sends.

Internal switches on the back panel offer deep customization without the hassle of so ware editors. Choose between true bypass or buffered trails, activate Kill Dry for parallel rigs - send (aux) effects in the studio, and configure routing via the Assignment Switch (SOS or MISO).

Footswitch behavior is just as smart. In Independent mode, each footswitch toggles its engine on/off. In R1 XF mode, the right footswitch becomes a momentary controller that ramps either R1’s Swell or Excite to full - then returns it smoothly when released. Use it to perform bloom swells, shimmer bursts, gated punches, or on-the-fly freeze. Assign control via the R1 Control Assign Switch. You can also map an external expres

sion pedal to R2’s Excite or Swell using its own switch - the XP input accepts standard TRS expression pedals (up to 100k)

Despite all its power, Mirage is fast and intuitive. There are no menus, no screens - just direct access to deep features with a layout that invites experimentation. Mirage even remembers your power-up state (bypass or active) for seamless integration on stage or in studio.

Full Feature List

- Dual independent reverb engines - Dedicated controls per engine for hands-on shaping.

- Flexible routing setup: mono in series, stereo, independent dual mono, or mono to stereo configurations - easily adapts to complex gear rigs or in the studio.

- SEND/RETURN loop between engines - insert pedals between reverb stages for enhanced routing.

- 16 total algorithms split into two intuitive banks: vintage/classic and ambient/experimental.

- Studio-grade signal path with high headroom, clarity, and detail. Analog-dry signal path.

- Flexible footswitching modes - independent engine toggling or real-time ramp expression.

- Assignable external expression pedal input.

- Internal switches for routing and bypass mode selection.

- Direct, playable interface for instant creative results - no menus to navigate.

- Power supply (not included): Use an isolated 9V DC, 2.1 mm x 5.5 mm, center negative power supply.

- Max current consumption 210mA.

- Click-less true bypass design via high quality relay or buffered bypass with reverb trails.

- Power-up bypass/engage preset function for the footswitches.

- Top mounted jacks.

- Dark Abyss Blue die-cast enclosure.

- Compact, rugged enclosure - designed for road use without sacrificing control layout.

- (W x L x H) : 123 x 97 x 54 mm.

- Weight 457 g.

- Made in Greece.

Fortin Annouce the Release of the Fourteen Dual/Boost Drive Pedal

Fortin Amplification unveil the FOURTEEN: A dual-channel drive/boost pedal with unparalleled power and versatility.

Fortin Amplification is proud to announce the launch of the FOURTEEN, a groundbreaking dual-channel drive pedal born from the legacy of the acclaimed HexDrive. Originally developed by Mike Fortin for use within NeuralDSP’s Fortin plugins, the HexDrive quickly earned a reputation as the ultimate “screamer-style” boost for higher-gain guitar tones - and became a staple in the Fortin product line.

Building on this proven foundation, Mike has integrated his sought-after TS-style modifications - the F9 and F808 - into the new FOURTEEN. The result is a pedal that delivers unmatched tonal versatility and raw power for modern players.

Each of the FOURTEEN’s two identical, switchable, channels offers a selection of three distinct boost/drive modes, allowing users to shape their tone with precision and ease. With the addition of amp channel switching control, the FOURTEEN empowers guitarists to command their tone from a single, compact unit. The FOURTEEN is about control. It’s about power. And it’s about making sure you never sacrifice one for the other.

Key features of the FOURTEEN Dual Boost/ Overdive include:

- 2 identical, switchable, channels;

- Each channel has 3 modes - HD, F9 and F808;

- Assignable amp switching, the FOURTEEN can switch the amp channel, giving the player control of which stomp changes the amp. It also allows the player to assign an amp channel to whichever channel of the pedal they prefer;

Like every other Fortin pedal, the FOURTEEN is proudly made in the USA using only the highest grade materials selected for superior sound, response and reliability.

Announcing the Silicon Harmonic Percolator from Fredric Effects

With years of experience recreating the iconic Interfax Harmonic Percolator - a distinctive, rare and sought-after mid 70s fuzz pedal - Fredric Effects now offers the Silicon Harmonic Percolator.

It's a revised version that swaps the original germanium components for carefully chosen vintage silicon transistors from 1980s East Germany. Fredric Effects have been building a part-for-part clone of the original 1970s Interfax Harmonic Percolator for over a decade now, and an improved version of that hybrid Silicon/Germanium circuit as the Utility Perkolator for almost as long.

The Harmonic Percolator circuit is simple and versatile, and careful component selection can yield fascinating results. This modified version of uses only silicon transistors manufactured 40 years ago in the former East Germany, and clips the signal using a weirdo East German diode array. This result is an effect which tightens and focuses the sound of the Percolator. The Silicon Harmonic Percolator sits somewhere between fuzz and distortion - clearer and more defined than a traditional fuzz, but still wild and saturated when pushed. It's a distinctive evolution of a cult classic.

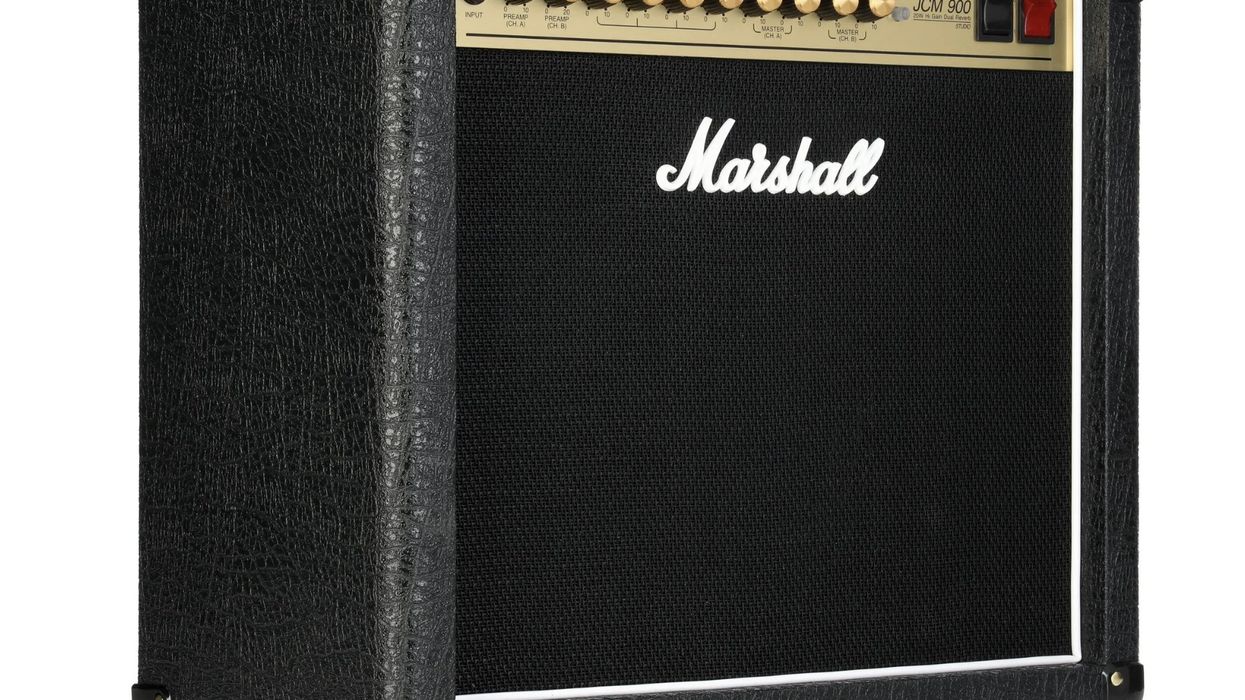

Marshall Studio 900 Review

Introduced in 2018, Marshall’s Studio Series amps are U.K.-made, compact, low-wattage renditions of past classics. They’re smart designs in light of the market’s turn to quieter, smaller amps, and they’ve earned Marshall kudos. Earlier Studio Series amps, like the SV20C and ST20C, were 20-watt mini versions of the original late-’60s Plexi and JTM45 models, respectively. Marshall also built Studio versions of the JCM800 and Silver Jubilee. Now, the JCM 900 Studio head and 1x12 combo captures the essence of the company’s high-gain sound of the ’90s.

Replicating the experience and sound of the 900s—the 50- and 100-watt, trouser-leg-flapping monsters from the golden age of grunge and metal—with a 20-watt output stage isn’t easy. As with the previous Studio models, one key to success is the use of large 5881 tubes, but in a cathode-biased output stage driven by lower plate voltages than in the big-bottle amps of old. Along with the ability to retain the beefy, full-throated sound of the originals, this approach yields longer life from tubes that are built to withstand much harder use. And, since the output stage is cathode-biased, a tube change means simply popping in a new pair of 5881s and off you go, with no re-biasing necessary.

Marshall aficionados will note that the JCM900 series amps were originally made with EL34 output tubes, and later 6L6s (which are direct substitutions for the 5881s used here). It was also fixed-bias rather than cathode-biased in both cases. In a circuit like this, though, the high-gain tone is driven much more by the preamp circuit, which is built around two 12AX7 tubes (plus another in the phase inverter). The Studio version also uses diode clipping to increase saturation levels in the style of the high-gain stage in the original 900 Series.

Ground Control

The JCM 900 Studio’s control layout follows a basic footswitchable two-channel topology with a shared EQ stage. Channel A is rhythm and channel B is lead. The knobs are for gain (the channel A preamp), lead gain (the channel B preamp), treble, middle, bass, presence, master reverb, plus master reverb and volume for channel A and master reverb and volume for channel B. There’s a push-button switch to engage the lead channel, but the included 2-button footswitch delivers that function plus reverb on/off. As part of Marshall’s mid-priced PCB-built range, the Studio Series might not fly with the top-shelf, hand-wired crowd, but inside, the construction is good-quality stuff.

The robustly built combo cabinet measures 21"x18"x10" and weighs 39.5 pounds and is dressed up in recognizably ’90s-era Marshall styling. The Celestion G12T-75 speaker within is shrouded by a ported back that’s much more closed than open, which should boost low-end girth relative to a more open-backed design. In addition to the 3-way output level switch, the rear panel includes two line outs (one standard, one recording compensated) with level control, effects loop send and return, one 16-ohm output for the onboard speaker, and outs for either 1x4-ohm, 2x8-ohm, 1x8-ohm, or 2x16-ohm speaker configurations.

Expansively English

Tested with a Gibson ES-355 and a Fender Telecaster, the JCM 900 Studio worked in perfect time-capsule-authentic ’90s fashion. Some players denigrate original 900 models for the fizz and sizzle that the solid-state, diode clipping adds to the lead tone. But 900s were used to make plenty of great heavy rock, grunge, and metal for decades, and by now, they are regarded as modern classics, especially for a certain set of ’90s-era tones. If you want those sounds, the JCM 900 Studio does the job very, very well. In fact, apart from the lower output making it less ideal for super-loud bands on big stages, it’s hard to hear how this new, smaller rendition suffers alongside an actual Model 4100.

“The Studio 900 is a petite, 20-watt Marshall that punches like its ’90s heavyweight inspiration, the JCM900.”

Channel A’s clean tones are useful, if not particularly characterful until you push the gain to edge-of-breakup territory. But it’s pedal-to-the-metal, guitar-god glory from the moment you stomp on the channel B switch. The key elements of 900 sounds—searing high-end bite, aggressive midrange, and low-end wallop— are all there in abundance. The dual master setup, lacking on much of the channel-switching competition, is a real bonus here, too. It enables you to rein in the rhythm channel independently to set up a broad spectrum of channel-to-channel dichotomies from smooth to jarring.

Channel switching makes the JCM 900 a surprisingly versatile amp, and the three output levels (20 watts, 5 watts, and 1 watt) selectable from the back panel make it even more so. No, the 1-watt setting won’t sound exactly like the 20-watt mode with the masters maxed, because 1 watt of output power simply doesn’t push the speaker or fill a room with sound in the same way. But with so much of this circuit’s tone coming from the preamp anyway, it will churn out surprisingly heavy doom riffs at bedroom volumes. The inclusion of reverb was also a standard feature of the original 900 Series amps, and while it is generally unacclaimed in those amps, the effect acquits itself quite well in the Studio 900. And between the reverb and the effects loop, the Studio 900 is a handy little package for adding atmospherics to clean or heavy tones.

The Verdict

As a real Marshall doing real ’90s-era tones in a compact, lower-output package, the JCM 900 Studio is a total success. For players keen to explore the widest range of sounds, I’d argue it’s more versatile than the Studio Jubilee, and it’s an interesting alternative to the JCM800-style Studio Classic. But used as a vehicle for strictly ’90s heaviness, it checks all the boxes at a fair and accessible price—especially when you consider the quality and extra versatility it delivers. . For players keen to explore the widest range of sounds, I’d argue it’s more versatile than the Studio Jubilee, and it’s an interesting alternative to the JCM800-style Studio Classic. But used as a vehicle for strictly ’90s heaviness, it checks all the boxes at a fair and accessible price—especially when you consider the quality and extra versatility it delivers.

Magnatone Baby M‑80 Slash Edition Demo

PG contributor Tom Butwin jumps into the Magnatone Baby M‑80 Slash Edition—12 watts of tube tone with clean sparkle, crunch, and high‑gain roar. With a master volume, Hi/Lo gain switch, effects loop, and backlit Slash logo, this amp brings full British flavor in a tiny frame. Whether you’re tracking at home or rocking live, it’s a compact beast you need to hear.

MagnatoneBaby M-80

SLASH SIGNATURE COLLECTION

Portable British-Style Warmth and Drive, Wrapped in Striking Purple Python. Available in a Head/Cab or a Combo.

Elevate your rig with the Baby M-80 “Purple Python” edition—where boutique tone meets bold style. Wrapped in hand-selected black and deep-purple snakeskin tolex with deluxe gold piping and hardware, this amp also features a gold-anodized faceplate with Slash’s “Skully” logo. This ultra-portable 12-watt powerhouse delivers the same legendary British crunch and creamy overdrive that Slash calls “the most kick-ass little combo I’ve ever played through.”

Beneath its striking exterior, the Baby M-80 is built around NOS 6AQ5 pentode power tubes that deliver 12 watts of warm, responsive output. The 12AX7 preamp section offers two gain settings, allowing you to move from clear, articulate cleans to gently saturated overdrive with the simple flip of a switch. A master volume knob ensures that the amp’s natural character remains intact whether you’re practicing at home or setting up for a small club gig. An effects loop sits between the preamp and power sections, preserving signal integrity when you introduce pedals or rack-mounted processors into your rig.

Each “Purple Python” Baby M-80 ships with a premium package of stickers and guitar picks. Handmade in our St. Louis workshop and crafted for tour-ready performance, it’s the perfect compact companion for studio, stage, or home. Designed under the guidance of engineer Obeid Khan, the Baby M-80 “Purple Python” series is offered as a combo, or a head with a matching 1×10″ extension cabinet loaded with a WGS ET 10 Speaker. For guitarists seeking an amp that balances portability, versatility, and a refined visual statement, the Purple Python Baby M-80 represents a thoughtful blend of form and function.

Tom Butwin Tests the Magnatone Baby M‑80 Slash Edition

PG contributor Tom Butwin jumps into the Magnatone Baby M‑80 Slash Edition—12 watts of tube tone with clean sparkle, crunch, and high‑gain roar. With a master volume, Hi/Lo gain switch, effects loop, and backlit Slash logo, this amp brings full British flavor in a tiny frame. Whether you’re tracking at home or rocking live, it’s a compact beast you need to hear.

PRS Guitars Adds Mark Holcomb Core Model to Catalog

Previously a limited run, this new signature model will be a constant

PRS Guitars today announced the return of a Mark Holcomb six-string signature guitar to the Core Series, 10 years after the original. Offered in 2015 as a limited release only, this new version will be a regular part of the Maryland lineup. Mark Holcomb, renowned for his groundbreaking work with progressive metal band Periphery, brings his signature style and precision to an updated guitar built for versatility and power.

The Mark Holcomb model features a mango top, a 25.5” scale length maple neck, and an ebony fretboard with a 20” radius—crafted for speed and precision. Equipped with Holcomb’s signature Seymour Duncan Scarlet and Scourge pickups, this guitar delivers focused low-end punch and crystal-clear articulation, ensuring complex chord voicings, coil-splitting, and drop tunings remain defined and dynamic. The 5-way blade switch unlocks a range of tones, from dual humbuckers in position three, to coil-split options in positions two and four.

“This new Core model is a culmination of all of the touring, recording, and writing I've done for the last 11 years with PRS and is a product of all the iterations PRS and I have done over that time. This guitar surpasses all of what we've established and is my new gold standard for tone and playability. Seeing it come to fruition is nothing short of a dream fulfilled. I couldn't be more proud of it, and I'm supremely grateful to PRS for their innovation and dedication to perfection,” said Mark Holcomb.

The model comes set up with PRS Signature 10-52 strings in Drop C tuning. It is appointed with satin black hardware and available in Charcoal Wraparound Burst, Holcomb Wraparound Burst, Holcomb Blue Wraparound Burst, Cobalt Smokeburst, Fire Smokeburst, Gray Black, and Purple Mist Wraparound Burst.

Holcomb’s innovative riffing, a cornerstone of Periphery’s dense triple-guitar sound, comes to life on stages worldwide with his PRS signature models. After the initial collaboration on a limited release of Holcomb signature Core models, Mark worked with PRS to create the SE Holcomb and the seven-string SE Holcomb SVN.

PRS Guitars continues its schedule of launching new products each month in 2025. Stay tuned to see new gear and 40th Anniversary limited-edition guitars throughout the year. For all of the latest news, click www.prsguitars.com/40 and follow @prsguitars on Instagram, Tik Tok, Facebook, X, and YouTube.

Fuhrmann Introduces Stellar Reverb

Brazilian pedal company Fuhrmann has introduced the Stellar, a stereo reverb processing unit in a compact pedal.

Featuring Fuhrmann's custom DSP and integrated 24-bit AD/DA converters, the Stellar’s reverb algorithm delivers a broad range of high quality reverbs, from short early reflections to long, floating tails.

Whether used for subtle spatial coloring or exploring more complex and dreamlike ambient textures, Stellar elevates performances to a new level while maintaining the “ease to use” characteristic of Fuhrmann pedals.

Like all Fuhrmann pedals, Stellar offers intuitive controls, allowing musicians to quickly get their ideal sound with minimal effort. In addition to the core parameters such as reverb time, effect Mix, Modulated, and Octave (which accumulates octaves to the reverb tail, providing a Shimmer effect), Steller offers variable high and low frequency filters to perfectly balance the reverb for your application. Furthermore, the analog signal is not processed (analog dry through).

Stellar includes memory to store 9 reverb scenes so that your favorite settings are always available. The pedal has two integrated footswitches that offer great convenience for programming your reverb sounds according to your needs. Through them, you will activate and deactivate the effect, navigate through the stored settings, or configure and save them, always practically and intuitively. It is worth noting that the presets are switched without delay.

In addition to stereo inputs and outputs, Stellar has MIDI I/O (TRS connector) to offer expanded control options, integrating it into any advanced setup. It can receive assignable commands from external MIDI controllers and devices, such as effects switchers.

Stellar uses 9-volt DC power from a standard external supply.

Fuhmann’s Stellar carries a $250 street price. For more information visit https://fuhrmann.com.br/

Electric Guitar Tonewood Teardown: Can We Get Good Sounds From Cheap Guitars?

Hello, and welcome back to Mod Garage. You asked for it, and Mod Garage delivers. Today, we will start a new little series and play “custom shop on a budget” together. We’ll talk about what is really important for the amplified tone of an electric guitar and prove all of this on the living object. We’re going to take apart a budget electric guitar down to the last screw, and we’ll see what’s possible to make it an excellent sounding guitar, step by step. I encourage you to follow along by getting yourself a similar electric and working in parallel to the column.

For this first installment, let’s have a closer look at the never-dying, snake-oil-drenched urban legends about tonewood on electric guitars and establish some parameters for our experiment. It’s very important to understand that we are talking about tonewood on electric guitars and their amplified tone exclusively; tonewood on acoustic guitars is a completely different thing. The rules for electric guitars are not applicable to acoustic guitars, and vice versa. In general, the whole discussion about tonewood is full of misunderstandings, inaccuracies, conclusions by analogy, biasing, and, of course, marketing bullshit of all kinds. And, sadly, a lot of this has developed into accepted internet knowledge by way of unfounded rumors.

Is the wood of an electric guitar the deciding factor of how it will sound? Or does the wood have no influence on its tone? I submit a resolute “no” to both theses: The truth here is much more complex, and, as usual, lies somewhere in between these two points. So, let’s try to find out exactly where that is!

There is no plant genus or tree called tonewood on this planet. That’s simply a word that’s intended to describe woods used to build instruments of any kind. In the context of stringed instruments, tonewood usually denotes woods that are traditionally used to build guitars. In the case of electric guitars, woods like alder, ash, maple, rosewood, and mahogany fall into this category, most of which have been used since the earliest days of electric guitar building. Let’s take alder and maple, for example. There are more than 40 alder and no less than 150 maple subspecies. Are they all tonewoods or only some of them? If it’s only some, which ones count? Did Leo Fender define what alder, ash, and maple subspecies get ennobled to tonewood? Let’s take a short journey back in time and see what Leo Fender cooked up in the early ’50s at 107 S. Harbor Blvd., Fullerton, California.

For his first electric guitars, Leo Fender used pine for the body (is pine a tonewood as well?) and maple for the neck. He soon switched to ash for the body, but stayed with maple for the neck. Why did Leo Fender choose these woods? Certainly not because of any tonal qualities. Ash and maple are lightweight, strong, easy to work with, and they were available in large quantities for a cheap price at the time. They were the perfect selections for Leo’s mass-production plans. Gibson decided to go with mahogany and maple, but for different reasons that also had little to do with tonal qualities. What exact types of maple, ash, and mahogany were used by Fender and Gibson? Well, nobody knows exactly, and the most likely answer would be: whatever was available cheap and in large quantities. It’s likely that even their wood suppliers didn't know exactly what subtype they were offering! These woods were probably chosen because of structural, optical, and economic reasons, yet they laid the foundation of the tonewood legend in electric guitars.

Interestingly, our bass-playing colleagues seem not to be caught in such paradigms, and all kinds of woods are used to build fantastic sounding electric basses today without the tonewood debate. Try to build a great-sounding electric guitar using cherry, pear, chestnut, oak, or birch; I’d venture that most people will tell you that it doesn’t sound right because it’s not made out of tonewood.

Now that we’ve established what tonewood is, let’s talk about the actual tone of these woods. Here’s a common comparison of ash and alder: In general, ash tends to produce a brighter, more articulate tone with good sustain, while alder is known for its warmer, thicker midrange sound. Ash, especially swamp ash, is often described as having a sweet, open top-end with a slightly scooped midrange. Alder, on the other hand, is perceived as having more pronounced mids and a potentially less defined low end. Sound familiar?

Here again, we have the problem of missing definitions and inaccuracies: Does this mean all kinds of ash and alder sound the same, no matter what subspecies they are? Is there a kind of general ash or alder tone? Assuming we’re talking about electric guitars, what tone are we discussing—the primary tone when strumming an unamplified electric or the amplified tone? Tonal descriptions are usually missing this important information.

“The correct question should be: How much of these tonal differences will be audible in the electrified tone of an electric guitar? Is the amplified tone simply a 1:1 copy of the primary acoustic tone?”

I think we can all agree that using different woods and hardware has an influence on the primary tone of a guitar, no matter if it’s an acoustic or an electric guitar. A cedar soundboard will create a much different tone than spruce or mahogany on an acoustic guitar, and an alder body on a Strat will sound different than ash, maple, or mahogany when playing it unamplified—not to mention the tonal impacts of different types of hardware on the guitar. So, the correct question should be: How much of these tonal differences will be audible in the electrified tone of an electric guitar? Is the amplified tone simply a 1:1 copy of the primary acoustic tone? Well, let’s try to find out.

A common scenario you can observe in guitar shops and on countless YouTube videos is the mandatory “dry test” when checking out a new electric guitar. The electric guitar is played like an acoustic guitar without being plugged into an amp. You can hear a lot of different answers for why such a test is important: You can feel how the wood resonates, what sustain it has, what overall tone it has, how much high-end chime is present, what the attack is like, etc.

Interestingly, all too often, criteria like playability and comfortability, defining how the guitar individually suits you, are omitted. How does the shape of the neck, the size of the frets, and the edge of the fretboard feel? How does the shape of the guitar fit your body when seated and standing? How does it intonate, how is the action, and how heavy is it? All of these factors determine to what degree the guitar will be a part of you, just like buying new jeans.

But what about the countless claims that the elements you hear in the dry test will be heard through the amp, too? Are these overly simplistic conclusions reached by analogy mixed with confirmation bias—an all-too-human reasoning process? Well, we’ll see.

You will have noticed that I haven’t made a single judgement until now; I’m just collecting facts and asking questions, and I encourage you to think and research about all of these things yourself until next month.

That’s when we will continue and finish our journey through the fantastic world of tonewoods for electric guitars, so stay tuned!

Until then ... keep on modding!

OC Pedal Co. Introduces their New Guitar Pedal the LA HABRA Hard Clipper

OC Pedal Co. has released the company’s second pedal, the LA HABRA Hard Clipper. This distortion captures some of the classic 80’s and 90’s drive tones we know and love.

The LA HABRA Hard Clipper is heavy, but still organic in its touch response, it’s kind of like fuzz for people who don’t like fuzz! The pedal’s interface is simple, it features a master volume, tone knob and a gain toggle switch allowing players to change the character of the clipping. The gain level is fixed! This unit shines through clean pedal platform type amps.

Key pedal features include:

- 80’s/90’s distortion tones

- Stacks well with overdrives

- Two clipping profiles to change the character of the distortion

- True bypass on/off switch

- 9-volt operation via standard external DC input (no battery compartment)

- Top-mounted input/output/DC jacks for easy pedalboard installation

- Designed and assembled in USA

The OC Pedal Co. LA HABRA Hard Clipper carries a street price of $179 and is available direct to consumer at www.ocpedalco.com

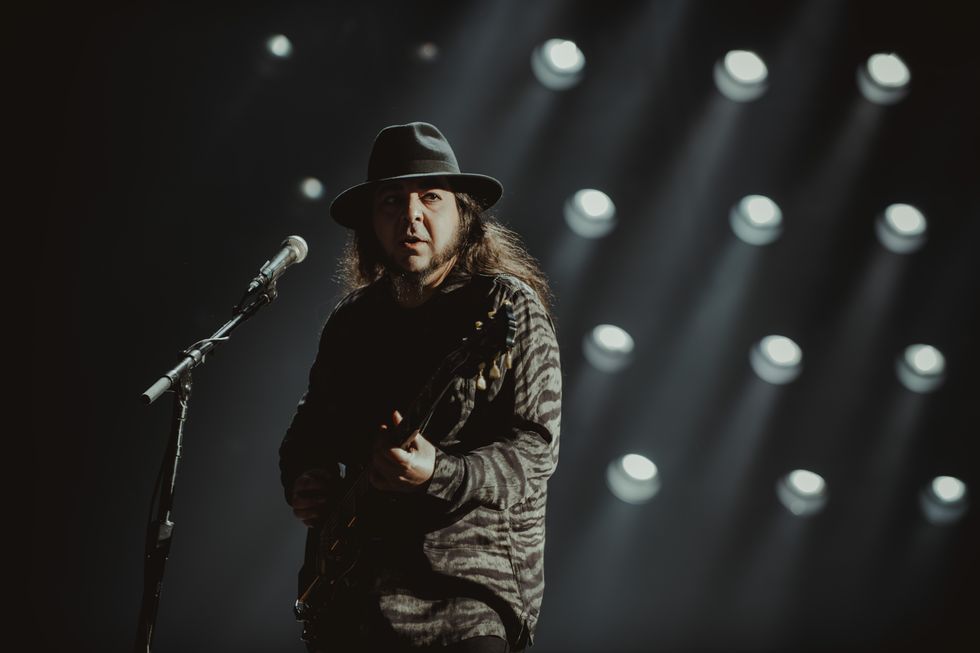

Daron Malakian’s Scalding Hot Melting Pot

Daron Malakian doesn’t believe everything he writes should be recorded right away, and he doesn’t craft songs in front of a computer with a DAW. “I guess I’m old school that way,” he confesses. “I just sit with my guitar on my couch, and if I come up with a good idea I record it on my [smartphone] voice memo.” Over time, he’ll go back to those ideas, repeatedly, whenever he picks up his guitar. “I entertain myself that way, playing with it like a toy, and then, sometimes years down the line, I record it.”

-YouTube

Whether with System of a Down or his own band Scars on Broadway, Malakian’s melting-pot songwriting alchemy draws as much from his Eastern (Armenian) heritage as it does his Western (American) influences. This unforced approach to songcraft has been at the heart of his success ever since he burst onto the scene with System of a Down’s eponymous debut in 1998. System released Toxicity in 2001, featuring their controversial, breakout single “Chop Suey!” and the epic, requiem for life’s meaning, “Aerials.” In 2005, they released two albums, Mezmerize and Hypnotize, the former featuring “B.Y.O.B,” which earned them a Grammy Award for Best Hard Rock Performance. For a band that only released five full-length albums between 1998 and 2005—three of which debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard 200—System of a Down sure left an indelible imprint on hard rock and heavy metal with their socially provocative lyrics and drop-tuned guitar manifestos.

Malakian launched Scars on Broadway and released their self-titled debut in 2008 largely because System had become inactive. In 2018, he issued Dictator, simultaneously rebranding the outfit as Daron Malakian and Scars on Broadway, citing the fact that he envisioned a rotating cast of musicians rather than a singular lineup. The third Scars album, Addicted to the Violence, dropped on July 18. On each record, Scars delivers lyrics that are in line with the social themes that fuel System’s worldview. Musically, however, Malakian doesn’t seem bound by genres or interested in recreating the success of past endeavors. The binding ingredient in his sound is simply to be honest as an artist.

“I have to be open to using whatever colors the song is asking for.”

“I’m going to make a Beatles reference, but I always want to be careful,” he clarifies. “I’m not putting myself on their level, but when you listen to the Beatles and you hear, [sings] ‘Michelle, ma belle…,’ then ‘Helter Skelter,’ then ‘Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,’ it shares the same DNA, but it’s so different stylistically. I’m not saying I achieved that on the same level, but I like artists that go through phases.” He cites Iggy Pop’s The Idiot, produced by David Bowie, as a prime example. “When you listen to that album it’s just so different from the Stooges. Having said that, the Ramones kept the same formula, and I freaking love the Ramones, so nothing against those guys, but it’s not what I do.”

Take “The Shame Game” on Addicted to the Violence. After the up-tempo, aggressive, one-two-three socio-political punch of “Killing Spree,” “Satan Hussein,” and “Done Me Wrong,” the mid-tempo song drops in, grabbing the listener’s attention with a dark, foreboding guitar part that completely shifts the tenor of the album, from heavy-on-the-riffs cultural insanity to mid-tempo atmospheric musical empathy. It’s an epic detour that enhances not only the track listing but exemplifies the yin and yang of Malakian’s songwriting, whether it’s the back and forth between mid- and up-tempo numbers or the amalgam of emotions and influences present in any given tune. Most importantly, “The Shame Game” reflects his patience when it comes to crafting a song, and is a great example of how Malakian can sometimes spend years toying with an idea.

“I used to start that song with the vocals: [sings] ‘Ain’t no shame in your game,’ but I was never really happy with it,” he explains. “I even recorded it that way when I first started working on this album during the pandemic.” One day, while sitting with his guitar in his living room, the intro 6-string part spilled out. “I didn’t even really come up with it for ‘Shame Game,’” Malakian admits. “But when I put it there, it completed the song. And that only happened years after I wrote the bulk of the tune.”

Malakian practices this unobtrusive approach to songcraft not by imposing his ego onto his ideas, but rather by allowing the song to tell him what it needs. “If I didn’t have moments like ‘Shame Game’ or ‘Addicted to the Violence’ or ‘You Destroy You,’ it wouldn’t feel like me,” he explains, citing three songs from his new album that most embody his Armenian upbringing and broad musical palette. “I can’t just pick three colors and say, ‘I’m only going to use these colors for this piece of work.’ I have to be open to using whatever colors the song is asking for. Sometimes it’s going to be heavy and you’re going to want to mosh, sometimes it’s going to be emotional and you’ll want to sing along, and sometimes you’re going to laugh because it’s freaking ridiculous and funny and kind of stupid. And those are all the sides of human emotion I’ve always tried to express in my writing.”

Malakian’s view is that he is merely channeling whatever it is the universe has to offer, and his lack of an agenda creates the necessary space for the creative juices to flow. It’s one of the reasons he gives the songwriting process time. “I just let things happen very naturally, and whatever sticks with me, sticks with me,” he attests. “Sometimes I don’t even feel responsible for it, like, ‘How the fuck did that just come out of me?’ Everything I do is subconscious.” When System first came out, for example, he says people would often focus on the Armenian influence in their music. “We were like, ‘We’re really not trying to write like that.’ It’s just part of the culture we’ve been around, so it’s bleeding into what we’re doing without us really trying to make that happen. It just happens.”

Daron Malakian’s Gear

Guitars

1962 Gibson Les Paul SG Standard

1968 Gibson ES-335

Amp

Dave Friedman-modded ’70s Marshall JMP100

Effects

Boss DD-6 Digital Delay

MXR M101 Phase 90

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball 2215 Skinny Top Heavy Bottom (.010–.052)

Jim Dunlop Delrin Triangle .96 mm picks

Malakian grew up in Los Angeles and went to an Armenian private school, where he also attended church. It was there he first got into music, via singing, long before picking up a guitar. “I would sing Armenian church-chant kinds of things,” he recalls. He subsequently wrote a lot of the melodies in System of a Down (“Serj [Tankian, System lead vocalist] might be singing them, but I wrote a lot of those vocal lines”), and is the main lyricist and singer in Scars. His family lived in a small apartment when he was an adolescent, so he couldn’t have any loud instruments. He actually wanted to be a drummer, but didn’t get his first instrument until his family moved into a house when he was 11, and he finally got his own bedroom. “Guitar happened by accident,” he says. “I’m happy that it happened, but my parents didn’t buy me a drum set because you couldn’t turn it off. [laughs] To this day, I’m more interested in vocalists and drummers than I am guitar players.”

“I actually have to stretch myself to get bluesy.”When Malakian’s parents did eventually buy him a small amplifier and a guitar, he says, “I was like, ‘Alright, this is what I’ve got. Let me see what I can do with this thing.’” He spent hours in his room playing, but instead of focusing on guitar chops, songwriting became his passion. “I found my own voice through writing songs,” he recalls. He’s so song-driven, in fact, that he wrote much of the first Scars record primarily using synthesizers and drum machines, which imbued the early demos with “electronic-goth vibes.” When he assembled a band, he introduced those songs to the unit with his guitar. “Songs like ‘Funny,’ ‘They Say,’ ‘Whoring Streets’ [from Scars on Broadway], and even ‘Guns Are Loaded’ [fromDictator] were all written on synthesizers before becoming guitar-driven rock songs,” he admits. When he transitioned them to guitar for band rehearsals, he says, “I found myself playing things that I wouldn’t have come up with had I come up with them on the guitar.”

The solo in “Done Me Wrong” is an example of how the Armenian influence can seep into Malakian’s songwriting with a bit more intentionality, and that it’s not necessarily the guitar that needs to be the focal point of his tunes, even when soloing. “The solo that you hear in the middle of the song, that keyboard, synthesizer-style, is the type of solo that you’ll hear in Armenian wedding-pop-dance music,” he explains. “I co-wrote that song with my guitar player, Orbel Babayan, and it drives very much like Deep Purple in the way that the rhythm moves. And like Deep Purple, we wanted that kind of solo, not in a neoclassical way, but more like what we call ‘Rabiz’ in Armenian music.”

Malakian says that blues-rock-based riffs and motifs don’t come as naturally to him as they would to someone who was raised on American rock ’n’ roll. Conversely, styles like Rabiz do come more naturally to him than they might to your average Westerner. “I actually have to stretch myself to get bluesy,” he admits. “That’s just because of where my family comes from and the community that I grew up in. But I was born and raised in the United States, so I was influenced by rock, metal, and pop radio, too.”

“I always tell people when you put out an album it’s forever.”

Ever since System’s Mezmerize and Hypnotize albums, Malakian has pretty much kept the same “heavy” guitar tone for recording. His main amp is a Dave Friedman-modded Marshall 100-watt JMP100 from the ’70s. For guitars, he relies on his 1962 Gibson Les Paul SG Standard and a 1968 Gibson ES-335. “We had the fires in L.A. back in January, and I had to evacuate,” he recalls. “I left all my guitars except for those two. I cannot replace them.” For recording, he generally stacks those guitars on top of each other. “The semi-hollowbody just explodes sonically, so I often use that for my heavy tone.” During System’s heyday, he layered a lot of guitars on top of each other, but with Scars, he doesn’t. “On this record, I didn’t really bust out a million guitars,” he says of Addicted to the Violence. He doesn’t employ many effects, either. “Sometimes I’ll use a phaser or a delay, but I’ve never been that crazy about using effects.” A hallmark of Malakian’s guitar sound is the crispness and crunchiness of his rhythm tone, a testament to these vintage axes and his minimalist approach.

Malakian’s early relationship with Rick Rubin, with whom he co-produced System of a Down’s albums, also had a significant impact on his songwriting and record-making ethos. “I’ve never had another producer aside from Rick Rubin, so his production style is what I bring to my mindset—it’s not technical at all,” he explains. “He’s someone who guides you on a journey and gives you advice.”

When Malakian wrote “Lost in Hollywood” [from Mezmerize] and brought the song to the band, Rubin looked at him and said, “It’s good, but it’s not finished.” Malakian recalls, “I thought it was finished, but that night I got home and that whole middle section came out of me. [sings] “I was standing on the wall, feeling 10 feet tall…’ It came out of nowhere.” Now, he says, he can’t even imagine the song without that part. “It’s the best part of the whole fucking song,” he attests. “Did he turn a knob? Did he fine-tune my guitar sound? No, but he made my song better just by giving me a little nudge and saying, ‘I don’t think it’s finished.’ I hear some people have experiences with Rick and they’re like, ‘He didn’t do anything.’ If you want your hand held through the whole fucking process and someone to sit there to be your motivation while you’re doing your guitar tracks, he’s not that guy.”

At this point in his career, Malakian has the luxury of not having to shoehorn his creativity into record company deadlines or marketing campaigns. He likens his artistic mindset, which leans towards capturing moments of divine inspiration, to preparing a meal. “I always tell people that when you put out an album it’s forever,” he says. “And because it’s forever, I don’t mind taking forever to finish that thing that’s going to be forever. You don’t serve a meal until it’s done cooking. And I’m in no rush.” He laughs. “It’s done when it’s done, and it will taste better to you that way.”

YouTube

Listen to Daron Malakian and Scars on Broadway’s Addicted to the Violence in its entirety.

Amyl and the Sniffers Rig Rundown with Declan Mehrtens & Gus Romer

Declan Mehrtens and Gus Romer brought the heat for the punk quartet’s storming spring headline tour.

Australian punks Amyl and the Sniffers have had a pretty good year. In October 2024, they released their third full-length, Cartoon Darkness, and opened a run of North American shows for Foo Fighters. This year, they warmed up the stage for the Offspring for a handful of shows in Brazil, then tore off across the United States and Canada for a headlining tour.

Ahead of their stopover at Nashville’s Marathon Music Works, PG’s Chris Kies met with guitarist Declan Mehrtens and bassist Gus Romer to see what weapons the Aussie invaders are using to conquer the music world.

Brought to you by D’Addario

300 Club

Mehrtens reckons he’s played around 300 gigs with this trusty Gibson Explorer, and it was used on just about every track on Cartoon Darkness. While recording, he equipped it with flatwound strings and a Lollar P-90 pickup in the bridge, but for tour, it’s got a Seymour Duncan Saturday Night Special in the bridge in addition to its stock neck pickup. It’s tuned a half-step down, and an identical (though less beat-up) Explorer is on hand in case this first one goes down.

Deluxe Dreams

This Fender Telecaster Deluxe comes out for the set’s softest song, “Big Dreams.”

Marshall and Friends

In addition to his beloved JCM800, Mehrtens is running a Hiwatt Custom 100, a model he discovered in Foo Fighters’ studio. Both are dialled in for a general-purpose rock tone, and an always-on Daredevil Drive-Bi, kept behind the stacks, runs into the Hiwatt to push it into breakup.

Declan Mehrtens’ Pedalboard

The jewel of Mehrtens’ board is his SoloDallas Schaffer Replica, famous for its recreation of Angus Young’s guitar tone. In addition, he runs a TC Electronic PolyTune 3 Noir, Electro-Harmonix Soul Food modded with LED diodes, MXR Micro Flanger, two MXR Carbon Copy Minis, and a Vox wah pedal. A switcher with six loops, built by Dave Friedman, manages the changes.

P for Punk

Romer plays this Fender Precision Bass, which is either a 2023 or 2024 model, though he insists the “P” in P bass stands for “punk.”

Three-Headed Beast

Romer’s signal is split into three channels: One split comes after his tuner, and runs clean to front-of-house, another channel runs direct and dirty from this Ampeg SVT Classic, and the last runs through his cabinet into a Sennheiser MD 421.

Gus Romer’s Pedalboard

Romer’s board, furnished with the help of Mehrtens, gets right to the point: It features a TC Electronic PolyTune 3, a Boss ODB-3, and an MXR Distortion+.

Gibson Explorer

Fender Deluxe Telecaster

Marshall JCM800

TC Electronic PolyTune 3 Noir

MXR Carbon Copy Mini

MXR Micro Flanger

EHX Soul Food

Vox wah pedal

Boss ODB-3

MXR Distortion+

TC Electronic PolyTune 3

Fender Precision Bass

Ampeg SVT Classic

Seymour Duncan Saturday Night Special

Asheville Music Tools Analoger APH-12 Review

At the end of the very thorough—and essential—manual that accompanies the Asheville Music Tools APH-12 phaser, designer Rick “Hawker” Shaich sweetly dedicates the pedal to the memory of the Grateful Dead’s bassist Phil Lesh. In fact, there are several references to the Dead in the manual—most pertaining to the APH-12’s ability to mimic Jerry Garcia’s envelope filter tones. But it is probably Lesh, the Dead’s relentless experimentalist, that would have appreciated the impressive, immersive APH-12 the most. Because while the all-analog APH-12 excels in rich conventional phaser sounds, it is capable of radical filtering and EQ effects, vibrato, tremolo, ring modulation, and more that would have been right at home on 1968’s Anthem of the Sun, the Dead’s mad-scientist production apotheosis. But you certainly don’t need to be a Deadhead to appreciate the sounds and craft that distinguish the APH-12. If you dig peppering your own productions and compositions with distinctive, weird, arresting textures—or just buttercream-thick phaser sounds—the APH-12 is a feast of treats that can transform a tune.

12 Stages, Infinite Roads

The fact that Hawker once worked as an engineer for Moog is a less-than-well-kept secret. And it’s impossible to not be excited about the APH-12 in the context of the Moogerfooger MF-103 phaser, a Bob Moog modulation masterpiece that Hawker helped refine during his tenure. With its 12-stage capability, drive control, and LFO section, many aspects of the APH-12’s features and functionality mirror those of the MF-103. But the APH-12 has a very different architecture. Where the MF-103 featured just 6- and 12-stage phase effects, the APH-12 is capable of 2- and 4-stage phasing as well as single-stage and odd-numbered staging that yield unusual, colorful out-of-phase effects. It also features an envelope-controlled mode that enables dynamic command of the modulation.

Learning how all these functions work together takes time. Though Hawker initially conceived the APH-12 as the company’s first analog/digital hybrid pedal, his ears led him back to an all-analog design. That means you can’t rely on presets to capture sounds derived from sensitive and interactive controls. You have to pay attention and probably take notes. But the process of decoding the APH-12’s secrets is instructive, engaging, immersive, and intuitive in its way, and learning its language is addictive stuff that often yields musical gold.

You Can Always Go Home