Music is the universal language

“Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace to those on whom his favor rests.” - Luke 2:14

Norse Guitar Feeds

“I sold it to Bob Rock for the same amount I paid for it. Just after that, the ‘Slasheffect’ happened… he sold it for 15times what he paid”: Billy Duffy on the Les Paul ’Burst he sold on the cheap – and why player-grade beats all-original every time

“Cliff played guitar as well as bass – I picked up a few things from him that ended up on Master of Puppets”: Before Robert Trujillo and Jason Newsted, Cliff Burton set the musical bar for Metallica and established an indelible legacy

“They’re humbuckers but have an amazing, almost Dumble harmonic range”: Keith Urban offers first look at his Tele-inspired PRS signature model

The Musical Colors of Andy Summers

It was December 1982, and the Police, barely tolerating one another, were recording their final album, Synchronicity, at legendary producer George Martin’s AIR Studios in Montserrat. As the band’s skillful and creative guitarist, Andy Summers, recounted recently to YouTuber Rick Beato, the band was sitting with a synth-laden version of the soon-to-be mega-hit “Every Breath You Take” that no one quite cared for. With the song then being stripped down to basic tracks and songwriter Sting asking Summers to “make it your own,” the guitarist proceeded to record—in one take—the now-famous guitar hook that catapulted the song to #1 on Billboard’s pop chart.

Last June, Summers released his latest solo album, the adventurous Vertiginous Canyons, which you can read more about in the fun and incisive Andy Summers: The Premier Guitar Interview. So, let’s take this opportunity to revisit the guitarist’s unique creativity in some of the Police’s classic songs, as the band weaved together elements of rock, punk, reggae, and jazz.

Chords Are Key

So much about music and guitar playing, even soloing, begins to make more sense as you develop a better understanding of chords, a key part of Summers’ musical foundation. Ex. 1 is based on the aforementioned classic part in “Every Breath You Take.”

Ex. 1

Solid fret-hand fingering is important in order to be able to pull this off as smoothly as Summers does in the above video. He is notably employing a palm-mute throughout, which frees him from being overly concerned with the notes ringing over each other, and he can maneuver his fret-hand index finger to jump to non-adjacent strings. Let’s tackle Ex. 1 using his method. For the Eadd2 chord, use your index and pinky to fret the 5th and 4th strings, respectively; then, shift your index finger to the 3rd string to fret the G#. The only other challenge is the F#m(add2) chord, which you can fret with your index, middle and pinky, shifting your index finger as in the previous chord.

But what’s this “add2” stuff all about? Well, we’re in the key of E major, so let’s first take a look at its accompanying major scale: E–F#–G#–A–B–C#–D#. The notes of a basic triad (three-note chord) are the root, 3rd and 5th, with our E chord spelled E–G#–B. To the find the 2nd of any chord, simply count one step up the scale from its root. One step up from E is F#, which is indeed the note we’re adding to our E chord in the example. To add the 2nd to the F#m and A chords, we add a G# and B, respectively.

The 2nd can also be used in place of the 3rd in a chord, which Summers famously does in the opening riff of “Message in a Bottle” from 1979’s Reggatta De Blanc.

These chords are known as “sus2” chords, as adding the 2nd without the 3rd being present creates a suspension—the tension created by adding a non-chord tone. (You might also be familiar with sus4 chords.) Ex. 2 illustrates an easy way to add the 2nd to some open-position chords. For the Gsus2, the 2nd (A) is located on the 3rd string; for the Csus2, the 2nd (D) is both on the 4th and 2nd strings, and for the Fsus2, the 2nd (G) is located on the 3rd and 1st strings.

Ex. 2

Ex. 3 illustrates the very same concept, but involves stretched voicings Summers employs in “Message…” Note how satisfying it sounds to resolve the 2nd of Asus2 (B) to its 3rd (C#) at the end of the second bar. In much the same way, you can create drama in your own playing simply by being aware of this concept of tension and release.

Ex. 3

Summers’ Colors

A hallmark of Summers’ playing is how deft he is at adding all sorts of colors to chords, which he does quite often in a host of Police classics, including “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic” from 1981’s Ghost in the Machine.

Here, though, he takes a different tack. By allowing the same open strings to drone over each chord of the progression, new colors are created each time. Ex. 4 illustrates this in a similar fashion.

Ex. 4

We’re moving a simple 5ths shape up the neck on the 2nd and 4th strings, while letting the open strings do the heavy lifting. Sometimes these droning notes turn out to be basic chord tones (root, 3rd, or 5th), as in bar 1’s G6 chord, where the open G string is the root. However, the open E adds the 6th, lending its own unique flair. The open G is key to the next two chords, where it acts as the 7th of A7 and the root of Gmaj13/B. In that same chord, the open E becomes its 6th. (The 6th is the same note as the 13th, but is generally called the latter when the 7th is present, as it is here in the form of the F#). Adding the same open strings to the C chord in bar 4 would simply result in its 3rd (E) and 5th (G), so we took things up a notch by adding the suspended 2nd (D) on the 1st string.

Using Colors in a Different Way

So far, we’ve learned how to use colors to vastly expand our vocabulary of chords. But learning to recognize each color’s unique sound, while at the same time being able to visualize them on the fretboard, also massively revs up your soloing ability. A great way to do this is to learn to visualize where the color notes are located on the fretboard in relation to the chord shapes you already know. First, let’s create a compelling guitar melody (Ex. 5) over the same chords used in Ex. 1.

Ex. 5

Before actually playing it, reacquaint yourself with Ex. 1’s Eadd2 chord shape, noting that the added 2nd (F#) is found on the 4th string. Ex. 5 begins with that very same F# resolving up to G#, the 3rd. Now, play bar 1 while visualizing the Eadd2 chord shape. (If you prefer, you can visualize a basic open position E shape, noting where the 2nd can be located.) Much like how the CAGED system is structured, this same shape can be moved up the neck. (For more on CAGED, check out these Premier Guitar lessons.) For example, let’s try finding the same melody over a Gadd2 chord by first moving our Eadd2 shape up to the 3rd position, creating a Gadd2 chord, with its root found on the 6th string, 3rd fret). It requires stretching your fingers a bit, but here, actually playing the chord isn’t our focus. Instead, simply visualize the shape, noting how its 2nd (A) is again found on the 4th string. Next, play Ex. 6, which is our same melody, arranged to function over a Gadd2 chord. This same process can be repeated for the F#m(add2) and Aadd2 chords, and to visualize any added color note or suspension.

Ex. 6

Finally, let’s loosen things up by playing a similar melody, but more in the style of a guitar solo, primarily by adding some bends, as in Ex. 7.

Ex. 7

In similar fashion, exploring Andy Summer’s style, especially his vast knowledge of chords, reveals a depth to his playing that can be mined to open up new worlds to boost our own creativity.

The Musical Colors of Andy Summers

It was December 1982, and the Police, barely tolerating one another, were recording their final album, Synchronicity, at legendary producer George Martin’s AIR Studios in Montserrat. As the band’s skillful and creative guitarist, Andy Summers, recounted recently to YouTuber Rick Beato, the band was sitting with a synth-laden version of the soon-to-be mega-hit “Every Breath You Take” that no one quite cared for. With the song then being stripped down to basic tracks and songwriter Sting asking Summers to “make it your own,” the guitarist proceeded to record—in one take—the now-famous guitar hook that catapulted the song to #1 on Billboard’s pop chart.

Last June, Summers released his latest solo album, the adventurous Vertiginous Canyons, which you can read more about in the fun and incisive Andy Summers: The Premier Guitar Interview. So, let’s take this opportunity to revisit the guitarist’s unique creativity in some of the Police’s classic songs, as the band weaved together elements of rock, punk, reggae, and jazz.

Chords Are Key

So much about music and guitar playing, even soloing, begins to make more sense as you develop a better understanding of chords, a key part of Summers’ musical foundation. Ex. 1 is based on the aforementioned classic part in “Every Breath You Take.”

Ex. 1

Solid fret-hand fingering is important in order to be able to pull this off as smoothly as Summers does in the above video. He is notably employing a palm-mute throughout, which frees him from being overly concerned with the notes ringing over each other, and he can maneuver his fret-hand index finger to jump to non-adjacent strings. Let’s tackle Ex. 1 using his method. For the Eadd2 chord, use your index and pinky to fret the 5th and 4th strings, respectively; then, shift your index finger to the 3rd string to fret the G#. The only other challenge is the F#m(add2) chord, which you can fret with your index, middle and pinky, shifting your index finger as in the previous chord.

But what’s this “add2” stuff all about? Well, we’re in the key of E major, so let’s first take a look at its accompanying major scale: E–F#–G#–A–B–C#–D#. The notes of a basic triad (three-note chord) are the root, 3rd and 5th, with our E chord spelled E–G#–B. To the find the 2nd of any chord, simply count one step up the scale from its root. One step up from E is F#, which is indeed the note we’re adding to our E chord in the example. To add the 2nd to the F#m and A chords, we add a G# and B, respectively.

The 2nd can also be used in place of the 3rd in a chord, which Summers famously does in the opening riff of “Message in a Bottle” from 1979’s Reggatta De Blanc.

These chords are known as “sus2” chords, as adding the 2nd without the 3rd being present creates a suspension—the tension created by adding a non-chord tone. (You might also be familiar with sus4 chords.) Ex. 2 illustrates an easy way to add the 2nd to some open-position chords. For the Gsus2, the 2nd (A) is located on the 3rd string; for the Csus2, the 2nd (D) is both on the 4th and 2nd strings, and for the Fsus2, the 2nd (G) is located on the 3rd and 1st strings.

Ex. 2

Ex. 3 illustrates the very same concept, but involves stretched voicings Summers employs in “Message…” Note how satisfying it sounds to resolve the 2nd of Asus2 (B) to its 3rd (C#) at the end of the second bar. In much the same way, you can create drama in your own playing simply by being aware of this concept of tension and release.

Ex. 3

Summers’ Colors

A hallmark of Summers’ playing is how deft he is at adding all sorts of colors to chords, which he does quite often in a host of Police classics, including “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic” from 1981’s Ghost in the Machine.

Here, though, he takes a different tack. By allowing the same open strings to drone over each chord of the progression, new colors are created each time. Ex. 4 illustrates this in a similar fashion.

Ex. 4

We’re moving a simple 5ths shape up the neck on the 2nd and 4th strings, while letting the open strings do the heavy lifting. Sometimes these droning notes turn out to be basic chord tones (root, 3rd, or 5th), as in bar 1’s G6 chord, where the open G string is the root. However, the open E adds the 6th, lending its own unique flair. The open G is key to the next two chords, where it acts as the 7th of A7 and the root of Gmaj13/B. In that same chord, the open E becomes its 6th. (The 6th is the same note as the 13th, but is generally called the latter when the 7th is present, as it is here in the form of the F#). Adding the same open strings to the C chord in bar 4 would simply result in its 3rd (E) and 5th (G), so we took things up a notch by adding the suspended 2nd (D) on the 1st string.

Using Colors in a Different Way

So far, we’ve learned how to use colors to vastly expand our vocabulary of chords. But learning to recognize each color’s unique sound, while at the same time being able to visualize them on the fretboard, also massively revs up your soloing ability. A great way to do this is to learn to visualize where the color notes are located on the fretboard in relation to the chord shapes you already know. First, let’s create a compelling guitar melody (Ex. 5) over the same chords used in Ex. 1.

Ex. 5

Before actually playing it, reacquaint yourself with Ex. 1’s Eadd2 chord shape, noting that the added 2nd (F#) is found on the 4th string. Ex. 5 begins with that very same F# resolving up to G#, the 3rd. Now, play bar 1 while visualizing the Eadd2 chord shape. (If you prefer, you can visualize a basic open position E shape, noting where the 2nd can be located.) Much like how the CAGED system is structured, this same shape can be moved up the neck. (For more on CAGED, check out these Premier Guitar lessons.) For example, let’s try finding the same melody over a Gadd2 chord by first moving our Eadd2 shape up to the 3rd position, creating a Gadd2 chord, with its root found on the 6th string, 3rd fret). It requires stretching your fingers a bit, but here, actually playing the chord isn’t our focus. Instead, simply visualize the shape, noting how its 2nd (A) is again found on the 4th string. Next, play Ex. 6, which is our same melody, arranged to function over a Gadd2 chord. This same process can be repeated for the F#m(add2) and Aadd2 chords, and to visualize any added color note or suspension.

Ex. 6

Finally, let’s loosen things up by playing a similar melody, but more in the style of a guitar solo, primarily by adding some bends, as in Ex. 7.

Ex. 7

In similar fashion, exploring Andy Summer’s style, especially his vast knowledge of chords, reveals a depth to his playing that can be mined to open up new worlds to boost our own creativity.

“The director said, ‘Fine, why don’t you just mime in that case?’ So we did – and air guitar was born”: Have the origins of air guitar finally been found? Unearthed footage contests the Joe Cocker at Woodstock ’69 theory

“As soon as I saw it my heart jumped into my throat – I’d bought it from a trusted guy and I couldn’t imagine that he would have done something improper”: This 1960 Gibson ES-335 proves that there’s always something to learn from vintage guitars

“It’s official. The age of touchscreen guitar amps is here”: This is all the new guitar gear that has caught my eye this week – and we might have a winner for the best new sub-$1k electric guitar of 2025

Totally Guitars Weekly Update July 11, 2025

July 11, 2025, Recently I have been having a good time revisiting songs by Elton John, partially inspired by a couple students working on old songs of his (i.e. ones that came out when I was in high school). Today’s Update started with some improvising on Love Song, written by Leslie Duncan and appearing on […]

The post Totally Guitars Weekly Update July 11, 2025 appeared first on On The Beat with Totally Guitars.

Greta Van Fleet guitarist Jake Kiszka says his bandmates are “very critical of guitar things” and have rejected some of his best riffs for the band

Greta Van Fleet are certainly doing their part to keep guitar music alive – but surprisingly, Jake Kiszka says his bandmates are “very critical of guitar things”.

In a new interview with Guitar World, Kiszka dives deep on Mirador, his other band he formed in 2024 with Chris Turpin of Ida Mae.

The band are set to release their debut album – which has been heard by Guitar World – and Kiszka explains how some of the riffs that ended up Mirador riffs were rejected by GVF.

One track, for example, on the new Mirador record is called Blood and Custard, named after an old nickname for Vox AC amps.

“I think that song is a perfect example of what type of things don’t necessarily translate in the world of Greta,” Kiszka explains.

“That was a riff I had for a long, long time. It’s just been sitting on the shelf. I would say I was influenced by the Eric Clapton and Duane Allman song Mean Old World, that kind of acoustic interpretation of a traditional blues song.

“So I had this thing hanging on the wall, and I wanted something with slide guitar on the record. Obviously, Chris is a great and very unique slide player, and I’m also known to play some slide, which I love doing. I put that riff to Chris and he loved it. He suggested Blood and Custard, which was an old nickname for the original Vox [AC] amplifiers – they had this cream-and-red binding. That’s a good [example of] guitar nerdism.”

As Kiszka reveals, his Greta Van Fleet bandmates passed on the riff.

“I think Josh [Kiszka, GVF singer and Jake’s brother] is very critical of guitar things,” he adds, “and it wasn’t something that he was particularly interested in. I don’t think it ever made it to the final stages.”

While Greta Van Fleet have now flourished into an arena band very much deserving of its place, they had to battle – and continue to do so, to a lesser degree – with those who accuse them of being derivative.

But they’ve always stuck to their guns. “I think people have realised we are sticking around and this is who we are,” Jake Kiszka said in 2023.

The post Greta Van Fleet guitarist Jake Kiszka says his bandmates are “very critical of guitar things” and have rejected some of his best riffs for the band appeared first on Guitar.com | All Things Guitar.

“Maybe that was part of the reason I had overlooked it before. It was so perfect and almost doesn’t stand out”: Alice Cooper’s new guitarist on why Glen Buxton is a seriously underrated guitar hero

"Crisply built and shines like a gem on the live stage": Taylor 314ce Studio review

Black Sabbath are done, but Tony Iommi is making another solo album: “I’m trying to finish what I started”

Black Sabbath might have finally thrown in the towel, but guitarist Tony Iommi hasn’t just yet. In fact, the Godfather of Heavy Metal has hinted at plans he has to finish a new solo album, his first in 20 years.

In a new conversation with Eddie Trunk of Trunk Nation, he reveals that he’s turning his attention back to the album, after it was diverted heavily by Back to the Beginning, Sabbath’s last-ever show and one of the largest heavy metal events ever put on.

“I was doing my own album until [Back To The Beginning] came up, and then, of course, I had to stop and concentrate on [preparing for] the Sabbath [performance],” Iommi tells Trunk [via Blabbermouth].

He goes on: “But I’m continuing next week on trying to finish off what I started with this album. And then who knows what I’m gonna do then? It’s great, really, ’cause if something pops up, I’ll do it, if I want to do it. So it’s a good thing.”

The album will be Iommi’s third solo outing, after the self-titled Iommi in 2000 and Fused in 2005. While Iommi featured a plethora of guest vocalists, his upcoming effort looks to be similar to Fused, in that only one singer is set to appear. Glenn Hughes sang on Fused, but the identity of the singer on this album has yet to be revealed.

“I’ve got one singer on it at the moment, which I originally thought of different singers,” Iommi continues. “But it started off as, ‘It’s gonna be an instrumental album,’ and it’s gone from, ‘I’ve got some instrumental stuff,’ but then I thought, ‘Oh, I wanna try it with a singer.’ And so that’s what I’ve been doing.”

As it stands, that’s the only information we have on the status of Iommi’s next solo outing. But we can forgive him for taking his time, given the magnitude of his commitment to Back to the Beginning.

The event – hosted at Villa Park in Black Sabbath’s hometown of Birmingham, England – so thousands of metal fans turn out to watch the genre’s A-listers, including Metallica, Slayer, Pantera and many more, pay tribute to the band who spawned their entire genre.

Sabbath performed a set at the end of the night with their original lineup of Ozzy Osbourne, Tony Iommi, Geezer Butler and Bill Ward.

The event also reportedly raised a staggering £140 million for charities chosen by Ozzy and Sabbath: Cure Parkinson’s, Birmingham Children’s Hospital and Acorns Children’s Hospice.

It also saw plenty of killer guitar moments – as you’d expect, being metal, and all – including Kirk Hammett wielding the CEO4, a guitar built by Gibson CEO Cesar Gueikian, during Metallica’s cover of Sabbath’s Hole in the Sky.

The post Black Sabbath are done, but Tony Iommi is making another solo album: “I’m trying to finish what I started” appeared first on Guitar.com | All Things Guitar.

Kirk Hammett’s mystery SG from Back to the Beginning was built by Gibson CEO Cesar Gueikian – and now it’s being auctioned off for charity

“With him doing his own set – which I didn't think he should do – I didn't want him to get burnt out”: Tony Iommi reflects on Black Sabbath’s final performance, his concerns over Ozzy's solo set – and reveals the songs they rehearsed but didn’t play

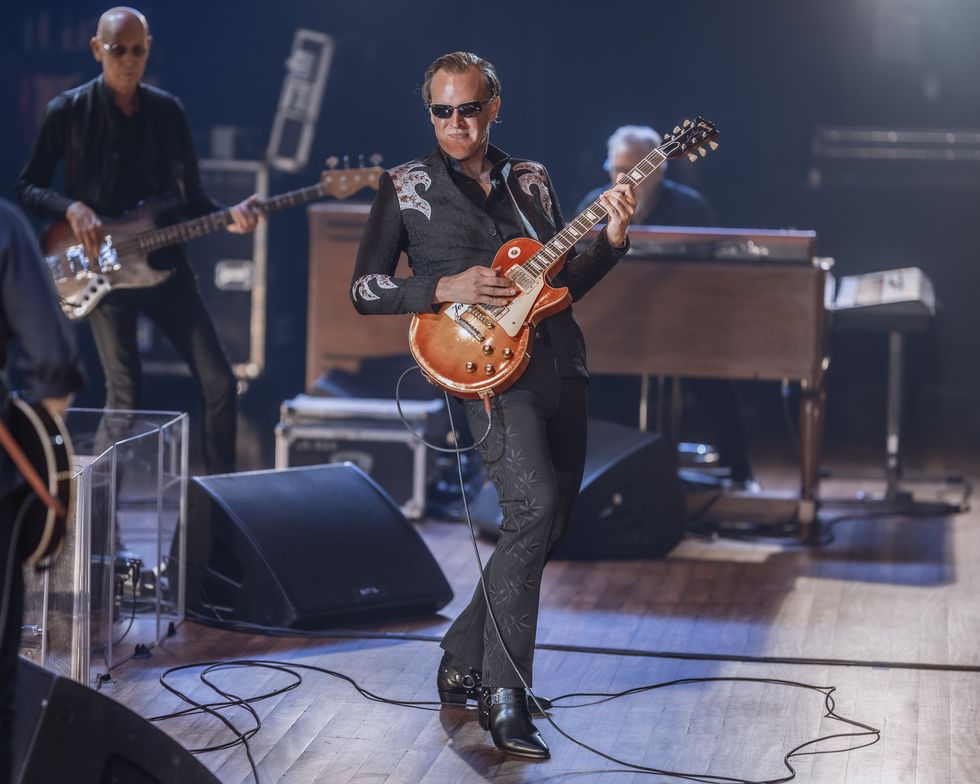

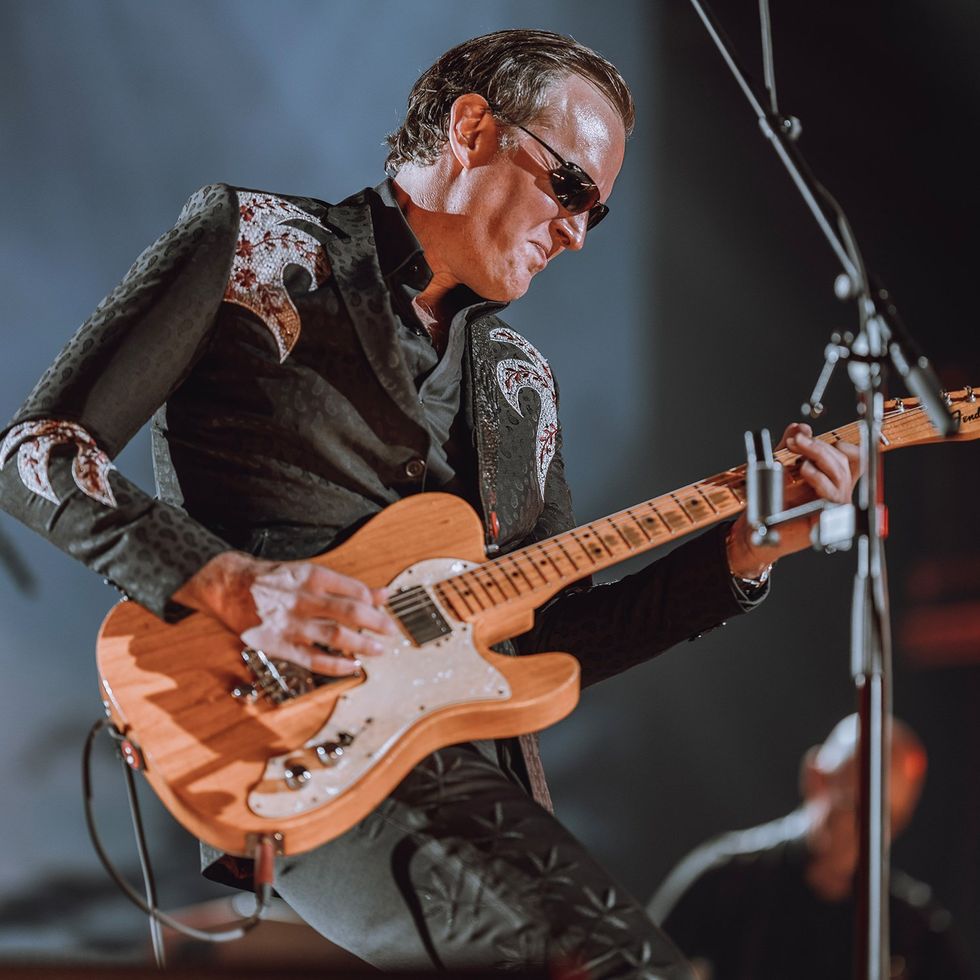

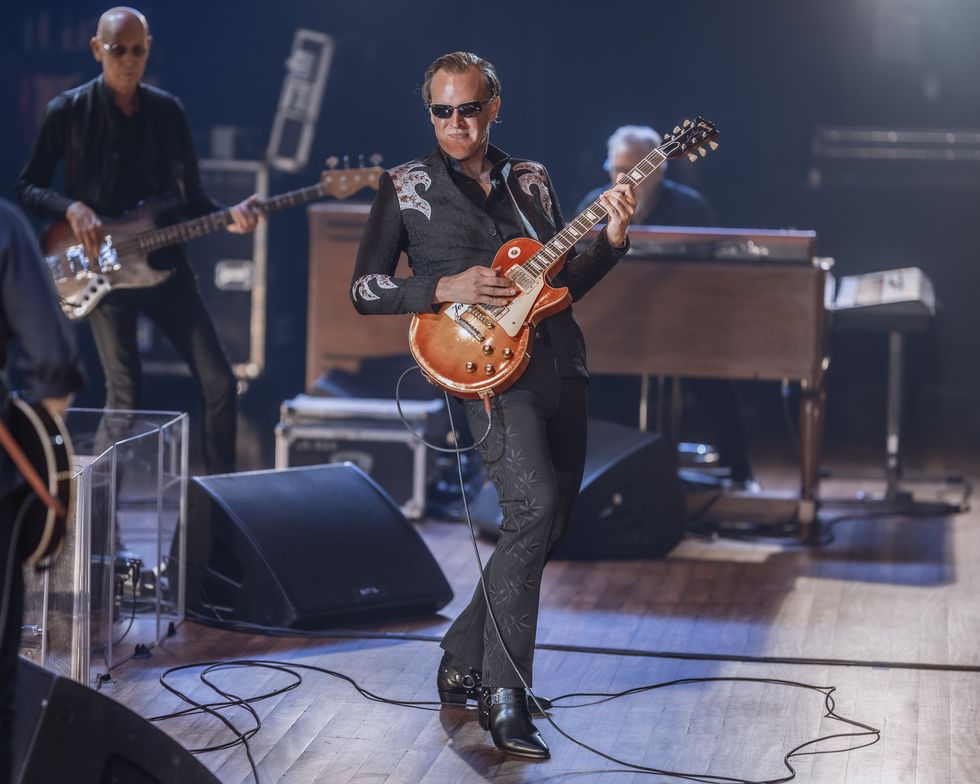

Evolution: Joe Bonamassa and His New Album, Breakthrough

The big-toned guitarist talks about his latest songs, discovering the allure of acoustic guitar, and the power of dividing by two.

Joe Bonamassa tends to go big. Big tones, big solos, big tours, a big gear collection, and a big road backline. His touring B rig boasts two Marshall Silver Jubilees, two Van Weelden Twinklelands, a Dumble Overdrive Special, a Benson rotary speaker, and a pair of his signature Fender High Power Twins. There’s also his A rig. That’s big.

And yet, as Bonamassa spoke from his hotel room in Frankfurt, Germany, he was planning to quietly celebrate his 48th birthday over pizza with his band. Then get a good night’s sleep. And recently he’s truly fallen in love with unplugged acoustic guitar—although when he used one to cut a song for his new album, Breakthrough, he ran it into a Fender DeVille and says, “It just exploded.”

That’s logical. Every great guitarist is a master of dynamics. And that sense of difference and balance reverberates in Breakthrough’s 10 songs, from the hard-edged, riff-driven title track, which features some blasting solos and stellar wah guitar, to the classic soul-pop flavor of “Life After Dark,” with its potent sustain and expressive bends, to the slide-dappled boogie of “Drive By the Exit Sign.”

Like nearly every post-Cream Eric Clapton album, regardless of how steeped in rock, pop hooks, and other flavors Breakthrough’s songs are, there is always the taste of blues, his bedrock, in the palate—whether it’s a lick, or a tone, or phrasing. And like Clapton, he uses expert songwriting to transcend the limitations of the timeless genre in the modern music marketplace. Still, it’s extraordinarily pleasing when Bonamassa goes all in on the slow blues “Broken Record,” a full-hearted essay in expressive playing and singing, evocative of Gary Moore.

When we spoke, Bonamassa talked about how acoustic guitar has impacted his evolution as a guitarist, explained the significance of the new album’s title, his DIY business model, and the power of dividing by two.

Joe Bonamassa’s Gear

(Note: Joe has similar A and B rigs that are hopscotched to suit tour logistics.)

The B Rig

Guitars

’77 Gibson Explorer

’63 Gibson Sunburst ES-335 with Bigsby

’62 Gibson Cherry ES-335

’63 Gibson SG

’54 Gibson Les Paul Jr. (all maple)

’54 Gibson Les Paul conversion

’59 Gibson Les Paul “Snake Bite’

’69 Gibson Les Paul “Royal Albert”

’55 Fender Strat

’59 Fender Strat (refinished)

’53 Fender Tele

’68 Fender Tele (wide range humbucker in neck)

Effects

Dunlop Joe Bonamassa Signature Cry Baby wah

Lehle 1@3

Dunlop Joe Bonamassa Signature Fuzz Face

EHX Micro POG

Vintage Ibanez Tube Screamer

Way Huge Conspiracy Theory

MXR Micro Flanger

Boss DD-2

Hughes & Kettner Rotosphere MkII

Strings, Picks, & Cables

Ernie Ball (.011–.013–.018–.030–.042–.052)

Dunlop JB Jazz III Gold picks

Klotz cables

Amps (with settings)

2 Marshall Silver Jubilee 2555s (presence, 4; bass,10; midrange, 6; treble, 4; out master, 10; lead master, 6; input gain, 5.5; each amp runs through half of a split Van Weelden 4x12 cabinet with Electro-Voice speakers)

2 Van Weeldon Twinkle Lands w/Twinklelator buffered effects loop (volume, 6; bright, on; deep, on; hot, on; treble, 6; midrange, 6.5; bass, 4; level, 6.5; ratio, 7; master, 7; brilliance, 6.5; each amp runs through half of a split Van Weelden 4x12 cabinet with Electro-Voice speakers)

Twinkelator effects loop settings: send, 7; return, 7; bright, off

Dumble Overdrive Special head (volume, 5; British, off; deep, off; rock, on; treble, 4; midrange, 6; bass, 4; overdrive level, 4; ratio, 6.5; master, 4; presence, 6; into 2x12 with TC Electronic Stereo Chorus)

Benson Rotary Speaker

2 Fender signature Joe Bonamassa High Powered Twins (volume 9; bright on; treble, 9; bass; 0, midrange, 9, presence, 7.5)

2 Kikusui PCR2000MA Power Supplies

Joe, when you’re at home hanging out with a guitar in your hands, what do you play?

You know, up until about five or six years ago, my answer would be completely different. I bought a guitar—a 1941 Martin 000-45, and it’s mint. It’s the one they based my model on. And it was so clean that I couldn’t play it. It’s so preserved. And right after that, I got a 1942 000-18 from my friend Jim Hauer in Dayton, Ohio, at Hauer Music. And once I had the neck set and it came back, I was like, “You know what? I get it now. I get the acoustic.” I’ve played a bunch of herringbones and stuff, but I was so focused on electric that acoustics would all sound the same to me. And then at some point, I said, “My God, I get it!” For years, I would just say I’m an electric guitar player, but I had that moment with the acoustic. So when I play at home, I vacillate between two guitars.

I have a room in my house in California … it’s, it’s … well, it’s documented how diseased I am. But if you can picture it, if I’m not playing electric, which is only if I’m working on something, I will pick up a 1929 000-42 Martin or a Joe B. Brazilian that Martin made me. It makes me happy. And I’ve found that my accuracy on the electric has improved by embracing the acoustic. I find, especially in the studio, if I’m producing a record and I’m playing on it, just the changes, my chordal accuracy, is a lot better.

And I finally figured out a way to, especially soloing-wise, embrace what Leslie West told me. Thirty years ago, his advice was to divide by two. He came to the studio in Ithaca, New York, when I was a kid working with Tom Dowd on what would be my first solo album. This was pre-production, and he guested on a track. And he, in that voice, goes: “You know, Joe, you’d be my favorite guitar player if you’d just divide by two.” I’m like, “You mean half as many notes?” He goes, “Right. Keep doing what you’re doing and divide by two.”

“For years, I would just say I’m an electric guitar player.”

Now, I’ve noticed a change in my playing. Especially when I’m touring and we’re playing big venues over here, I’ve been using “divide by two.” That and the acoustic thing I’ve been embracing for the last, say, 24 to 36 months has been paying off. Every once in a while you break through a frontier you didn’t even know you were gonna break through or didn’t even know existed.

I know I’m a paradox, but when I’m off the road, I try to avoid loud music and crowds. So I don’t play electric at home very loud, and I play these acoustics. When I plug a Les Paul into a Marshall or Fender Strat into a black-panel Princeton, the sounds you expect are going to come up and then it’s up to you to create something. But the acoustic … you’re just kind of wide open. I find that I’m coming up with more original ideas just by not playing electric when I’m home.

When you prepare for an album, are there some foundational guideposts or a specific artistic goal you’re working toward?

Historically, it was always like: this is the theme, this is what we’re doing, let’s execute it. And we have five days or seven days to do it. This record was different because I approached this album from the point of view that the world does not need another Joe Bonamassa record. So I’m trying not to repeat myself. That’s why we ended up with 20 songs that got jettisoned; 10 of which got jettisoned because we were like, yeah, I’ve heard that before. And we tried to concentrate on things that I haven’t done before, but when you have 50 albums out, including the live stuff, before you even get to the side projects, it’s hard. I think this is my 17th studio solo album.

We did this in three sessions, in Santorini, Greece; Nashville; and L.A.—with totally different approaches on each. The Santorini stuff has a certain sound because of the way we recorded it and the lack of options. I was just using the studio guitars. Like the song with Sammy Hagar, “Fortune Teller Blues”—the only guitar that was actually going to stay in tune was an Ovation acoustic, so I plugged it into a Fender Hot Rod DeVille, and it just exploded into the mic. I was like, “Okay, now that’s an interesting sound.” I had that and a Slash Les Paul, and I noticed that the pickups were hotter than what I was used to, but I just embraced it.

You just have to wrap your head around it. Any guitar that’s not in your normal comfort zone, just pretend it’s the only guitar you own. Because I bought plenty of guitars over the years from people who played them their whole lives and that’s the only guitar they owned. They did their whole musical life on that one guitar and they figured it out, you know?

Sometimes, having fewer tools is a lot better. A few records ago, I stopped bringing 40 guitars to the studio. How many Telecasters do you need? Pick one that stays in tune. How many Les Pauls do you need? The one you play every day. And then you bring the flavors: the 12-string electric, the acoustic, whatever. And I always bring my live rig and a couple of different things, like an AC30 or some sort of JTM45. Sometimes, as a collector, you’ve got to justify owning all this stuff. It’s like, man, I paid all this money for this thing; I’m gonna play it!

“Every once in a while you break through a frontier you didn’t even know you were gonna break through or didn’t even know existed.”

Well, you don't have to justify it to me. When I was starting to play, I had a friend who said, “You should have as many guitars as you want.” I took that to heart.

On the internet sometimes, the notion is that I’m depriving other people of having these guitars, because I have such a large collection, one of the biggest in the world. It’s such specious reasoning. How many of these guitars are for sale right now … at the Dallas Guitar show, the Heritage auction, Reverb, eBay, every guitar shop? They’re out there.

I’m surprised by some of the conversations I see about you online from the blues police. Complaints that if Joe wasn’t out there, some old bluesman of note would have those gigs. Except for Buddy Guy, nobody who was a sideman for Muddy Waters has a shot at headlining, say, Royal Albert Hall.

There’s a lack of critical thinking. You know all the gigs that I do, the arenas that we’re playing over here? Do you know who the promoter is? Me. So I’m not taking anybody’s gig. I’m creating my own weather pattern. Twenty years ago, we started promoting our own shows.

It’s proof of concept. Many times was I told, and anybody in this genre has been told, “See those big places over there? Those are not for you. Musicians like you don’t get to play those places.” Well, somebody had to try, and we wouldn’t still be doing that if nobody showed up. I can do everything but make them come out. And if people have a problem with that, if people have a problem with the guitar collecting that I do and the success I’ve had, that’s on them. It’s not on me to apologize for any of it. Because I grew up lower middle class in Utica, New York, and decided that I was gonna do something with my life or die trying. There’s always someone who works harder, who deserves it more than you. You have to just accept that. Then, there’s some luck involved. And what we’re doing as a team is connecting. That’s the records, the production, the marketing, all of it. There’s something there that’s connecting to a wider group of people that don’t normally go to blues shows.

“I approached this album from the point of view that the world does not need another Joe Bonamassa record.”

You mention a “do or die” attitude. At one point, you were trapped in the blues barbecue joint circuit, before you worked your way out.

It always felt that way. The really magic moment for me was 2009 at the Albert Hall when Eric Clapton came out to play with me, and I will always be extremely grateful to him for that. But you realize that if that was May 5, the day after that show, May 6, we were broke. We had put all of our money in the DVD we made there. And when it came out, it did okay. And we had just enough money to keep the machine going and try to build. And then it hit PBS. And after PBS, life changed about six months later. But when you're watching somebody on a DVD seemingly have it all, sometimes the story behind the scenes is way different than the reality.

Getting back to Breakthrough, it’s an eclectic album, and you’ve been co-writing with some of the most respected songwriters in Nashville roots music, like Tom Hambridge, Gary Nicholson, Keb’ Mo’. And is there something of a personal breakthrough that sparked the title?

I think there is a meaning there. I’m trying not to repeat myself, but not abandon ship. The only thing I’ve abandoned is the notion that anything I’ll do will be pop music at all. I’m a niche guy. I don’t have a radio voice. I’m not looking to get invited to the Met Gala.

I’ve written a lot of songs for other people as well, like Jimmy Hall and Eric Gales. You’ve got to come in with some sort of idea, riff, or a title. A title is great because you can write something about that. A riff is like, “Okay, then what are we going to say?” Then you’ve just got to have a conversation and start riffing on it. You try to find a broader concept and try to make it something that’s personal to you that will also be personal to your co-writer and the audience.

It surprises me when I go into these old tracks, live, and people start applauding. I’m like, “I had no idea you guys even knew this song.” I just assume everything I put out over my life has not been a hit, and we’ve survived and navigated like that, almost like a jam band.”

I’m not looking for a hit. And I don’t want anything to do with that shit that’s coming out of Music Row. None of it. And I’m not looking for radio. So it’s, “Let’s have fun and write a six-minute banger, shall we? With a big fat guitar solo that has no chance of being played on the radio.”

“Any guitar that’s not in your normal comfort zone, just pretend it’s the only guitar you own.”

Speaking of big fat guitar solos, my favorite song on the album is “Broken Record.” I’m a sucker for a slow blues, and over its 7 minutes, it goes to a lot of interesting places and has a cool tonal palette. I even like small, nerdy things about it—like the way the delay hangs at the end of the song. How did you put the tonal palette together for that one?

I remember this: The solo that’s on there was basically a placeholder because I got the call to pick up my car at the shop. I’m at the console, dialed up a quick sound, get a call from the mechanic going, “Hey, your car’s ready.” I called the Uber, and as I’m waiting for the Uber to take me to get the car on a Friday afternoon, because I didn’t want to leave it over the weekend, I go, “Let me just give you a placeholder and I'll be back in a half hour.” I come back in a half hour and everybody’s going, “I think that solo’s good.” And I go, “Okay.” And it was literally just stream of consciousness. The whole song—vocals, everything—was done in an afternoon. And that’s the way I like to work. I like to cut in the morning, get the two or three that we’re gonna do that day, buy the band lunch, tell them to fuck off, then I’ll sing and play, and that’s it. You’re gonna sing, play, and once you’re happy, that’s it. If you’re prepared and know how to do it and hit the marks, three takes of vocals, we’ll comp it, done, move on. We’re at dinner by 6 o’clock. I learned that from Kevin Shirley. [The producer who’s frequently collaborated with Bonamassa since 2006’s You & Me and returns for Breakthrough.] You burn very intensely from about 10 a.m. to about 5:30 or 6, and that’s it. I’m not a night owl in the studio.

I want to talk to you a little bit about Journeyman Records, which is a pet project label of yours and your manager, Roy Weisman. What’s the impetus? What do you get from it personally?

We have Joanne Shaw Taylor and Robert John, and we’ve invested in those two because what we see in them is little glimpses of what was happening with me right before it hit. You’re a very talented artist, but if a tree falls in the woods and nobody’s there to hear it, does it sell any tickets? [laughs] No. I learned that. So we’ve created a vertical integration of business for those artists—everything from concert promotion to T-shirts to having ownership of their masters.

If I said to you 20 years ago that I do my own T-shirts, I do my own record company, and I promote my own shows, the notion, on Sunset Boulevard at the Chateau Marmont, would be, “This person clearly is not talented and has to do it by themselves because nobody will help them.” Now, the conversation taking place is, “My god, I gotta re-record my album because I don’t own my masters.”

So we’re using Journeyman Records as a proof of concept. It’s like, if I could do it, anybody can. It just takes hard work. And Vince Gill said it best: “If you don’t bet on yourself, how are you going to get anybody to bet on you?” And that’s so true. Maybe it’s ego, it’s bravado, it’s blind belief … whatever you want to call it. It is so important to have that chip on your shoulder before you even enter into this. Because if you don't believe in what you’re doing, you’re going to encounter some headwinds that may not be surmountable.

YouTube It

This performance from the Rudolf-Weber Arena in Oberhausen, Germany, is from April 29, 2025 and showcases Bonamassa’s range as an artist.

Evolution: Joe Bonamassa and His New Album, Breakthrough

The big-toned guitarist talks about his latest songs, discovering the allure of acoustic guitar, and the power of dividing by two.

Joe Bonamassa tends to go big. Big tones, big solos, big tours, a big gear collection, and a big road backline. His touring B rig boasts two Marshall Silver Jubilees, two Van Weelden Twinklelands, a Dumble Overdrive Special, a Benson rotary speaker, and a pair of his signature Fender High Power Twins. There’s also his A rig. That’s big.

And yet, as Bonamassa spoke from his hotel room in Frankfurt, Germany, he was planning to quietly celebrate his 48th birthday over pizza with his band. Then get a good night’s sleep. And recently he’s truly fallen in love with unplugged acoustic guitar—although when he used one to cut a song for his new album, Breakthrough, he ran it into a Fender DeVille and says, “It just exploded.”

That’s logical. Every great guitarist is a master of dynamics. And that sense of difference and balance reverberates in Breakthrough’s 10 songs, from the hard-edged, riff-driven title track, which features some blasting solos and stellar wah guitar, to the classic soul-pop flavor of “Life After Dark,” with its potent sustain and expressive bends, to the slide-dappled boogie of “Drive By the Exit Sign.”

Like nearly every post-Cream Eric Clapton album, regardless of how steeped in rock, pop hooks, and other flavors Breakthrough’s songs are, there is always the taste of blues, his bedrock, in the palate—whether it’s a lick, or a tone, or phrasing. And like Clapton, he uses expert songwriting to transcend the limitations of the timeless genre in the modern music marketplace. Still, it’s extraordinarily pleasing when Bonamassa goes all in on the slow blues “Broken Record,” a full-hearted essay in expressive playing and singing, evocative of Gary Moore.

When we spoke, Bonamassa talked about how acoustic guitar has impacted his evolution as a guitarist, explained the significance of the new album’s title, his DIY business model, and the power of dividing by two.

Joe Bonamassa’s Gear

(Note: Joe has similar A and B rigs that are hopscotched to suit tour logistics.)

The B Rig

Guitars

’77 Gibson Explorer

’63 Gibson Sunburst ES-335 with Bigsby

’62 Gibson Cherry ES-335

’63 Gibson SG

’54 Gibson Les Paul Jr. (all maple)

’54 Gibson Les Paul conversion

’59 Gibson Les Paul “Snake Bite’

’69 Gibson Les Paul “Royal Albert”

’55 Fender Strat

’59 Fender Strat (refinished)

’53 Fender Tele

’68 Fender Tele (wide range humbucker in neck)

Effects

Dunlop Joe Bonamassa Signature Cry Baby wah

Lehle 1@3

Dunlop Joe Bonamassa Signature Fuzz Face

EHX Micro POG

Vintage Ibanez Tube Screamer

Way Huge Conspiracy Theory

MXR Micro Flanger

Boss DD-2

Hughes & Kettner Rotosphere MkII

Strings, Picks, & Cables

Ernie Ball (.011–.013–.018–.030–.042–.052)

Dunlop JB Jazz III Gold picks

Klotz cables

Amps (with settings)

2 Marshall Silver Jubilee 2555s (presence, 4; bass,10; midrange, 6; treble, 4; out master, 10; lead master, 6; input gain, 5.5; each amp runs through half of a split Van Weelden 4x12 cabinet with Electro-Voice speakers)

2 Van Weeldon Twinkle Lands w/Twinklelator buffered effects loop (volume, 6; bright, on; deep, on; hot, on; treble, 6; midrange, 6.5; bass, 4; level, 6.5; ratio, 7; master, 7; brilliance, 6.5; each amp runs through half of a split Van Weelden 4x12 cabinet with Electro-Voice speakers)

Twinkelator effects loop settings: send, 7; return, 7; bright, off

Dumble Overdrive Special head (volume, 5; British, off; deep, off; rock, on; treble, 4; midrange, 6; bass, 4; overdrive level, 4; ratio, 6.5; master, 4; presence, 6; into 2x12 with TC Electronic Stereo Chorus)

Benson Rotary Speaker

2 Fender signature Joe Bonamassa High Powered Twins (volume 9; bright on; treble, 9; bass; 0, midrange, 9, presence, 7.5)

2 Kikusui PCR2000MA Power Supplies

Joe, when you’re at home hanging out with a guitar in your hands, what do you play?

You know, up until about five or six years ago, my answer would be completely different. I bought a guitar—a 1941 Martin 000-45, and it’s mint. It’s the one they based my model on. And it was so clean that I couldn’t play it. It’s so preserved. And right after that, I got a 1942 000-18 from my friend Jim Hauer in Dayton, Ohio, at Hauer Music. And once I had the neck set and it came back, I was like, “You know what? I get it now. I get the acoustic.” I’ve played a bunch of herringbones and stuff, but I was so focused on electric that acoustics would all sound the same to me. And then at some point, I said, “My God, I get it!” For years, I would just say I’m an electric guitar player, but I had that moment with the acoustic. So when I play at home, I vacillate between two guitars.

I have a room in my house in California … it’s, it’s … well, it’s documented how diseased I am. But if you can picture it, if I’m not playing electric, which is only if I’m working on something, I will pick up a 1929 000-42 Martin or a Joe B. Brazilian that Martin made me. It makes me happy. And I’ve found that my accuracy on the electric has improved by embracing the acoustic. I find, especially in the studio, if I’m producing a record and I’m playing on it, just the changes, my chordal accuracy, is a lot better.

And I finally figured out a way to, especially soloing-wise, embrace what Leslie West told me. Thirty years ago, his advice was to divide by two. He came to the studio in Ithaca, New York, when I was a kid working with Tom Dowd on what would be my first solo album. This was pre-production, and he guested on a track. And he, in that voice, goes: “You know, Joe, you’d be my favorite guitar player if you’d just divide by two.” I’m like, “You mean half as many notes?” He goes, “Right. Keep doing what you’re doing and divide by two.”

“For years, I would just say I’m an electric guitar player.”

Now, I’ve noticed a change in my playing. Especially when I’m touring and we’re playing big venues over here, I’ve been using “divide by two.” That and the acoustic thing I’ve been embracing for the last, say, 24 to 36 months has been paying off. Every once in a while you break through a frontier you didn’t even know you were gonna break through or didn’t even know existed.

I know I’m a paradox, but when I’m off the road, I try to avoid loud music and crowds. So I don’t play electric at home very loud, and I play these acoustics. When I plug a Les Paul into a Marshall or Fender Strat into a black-panel Princeton, the sounds you expect are going to come up and then it’s up to you to create something. But the acoustic … you’re just kind of wide open. I find that I’m coming up with more original ideas just by not playing electric when I’m home.

When you prepare for an album, are there some foundational guideposts or a specific artistic goal you’re working toward?

Historically, it was always like: this is the theme, this is what we’re doing, let’s execute it. And we have five days or seven days to do it. This record was different because I approached this album from the point of view that the world does not need another Joe Bonamassa record. So I’m trying not to repeat myself. That’s why we ended up with 20 songs that got jettisoned; 10 of which got jettisoned because we were like, yeah, I’ve heard that before. And we tried to concentrate on things that I haven’t done before, but when you have 50 albums out, including the live stuff, before you even get to the side projects, it’s hard. I think this is my 17th studio solo album.

We did this in three sessions, in Santorini, Greece; Nashville; and L.A.—with totally different approaches on each. The Santorini stuff has a certain sound because of the way we recorded it and the lack of options. I was just using the studio guitars. Like the song with Sammy Hagar, “Fortune Teller Blues”—the only guitar that was actually going to stay in tune was an Ovation acoustic, so I plugged it into a Fender Hot Rod DeVille, and it just exploded into the mic. I was like, “Okay, now that’s an interesting sound.” I had that and a Slash Les Paul, and I noticed that the pickups were hotter than what I was used to, but I just embraced it.

You just have to wrap your head around it. Any guitar that’s not in your normal comfort zone, just pretend it’s the only guitar you own. Because I bought plenty of guitars over the years from people who played them their whole lives and that’s the only guitar they owned. They did their whole musical life on that one guitar and they figured it out, you know?

Sometimes, having fewer tools is a lot better. A few records ago, I stopped bringing 40 guitars to the studio. How many Telecasters do you need? Pick one that stays in tune. How many Les Pauls do you need? The one you play every day. And then you bring the flavors: the 12-string electric, the acoustic, whatever. And I always bring my live rig and a couple of different things, like an AC30 or some sort of JTM45. Sometimes, as a collector, you’ve got to justify owning all this stuff. It’s like, man, I paid all this money for this thing; I’m gonna play it!

“Every once in a while you break through a frontier you didn’t even know you were gonna break through or didn’t even know existed.”

Well, you don't have to justify it to me. When I was starting to play, I had a friend who said, “You should have as many guitars as you want.” I took that to heart.

On the internet sometimes, the notion is that I’m depriving other people of having these guitars, because I have such a large collection, one of the biggest in the world. It’s such specious reasoning. How many of these guitars are for sale right now … at the Dallas Guitar show, the Heritage auction, Reverb, eBay, every guitar shop? They’re out there.

I’m surprised by some of the conversations I see about you online from the blues police. Complaints that if Joe wasn’t out there, some old bluesman of note would have those gigs. Except for Buddy Guy, nobody who was a sideman for Muddy Waters has a shot at headlining, say, Royal Albert Hall.

There’s a lack of critical thinking. You know all the gigs that I do, the arenas that we’re playing over here? Do you know who the promoter is? Me. So I’m not taking anybody’s gig. I’m creating my own weather pattern. Twenty years ago, we started promoting our own shows.

It’s proof of concept. Many times was I told, and anybody in this genre has been told, “See those big places over there? Those are not for you. Musicians like you don’t get to play those places.” Well, somebody had to try, and we wouldn’t still be doing that if nobody showed up. I can do everything but make them come out. And if people have a problem with that, if people have a problem with the guitar collecting that I do and the success I’ve had, that’s on them. It’s not on me to apologize for any of it. Because I grew up lower middle class in Utica, New York, and decided that I was gonna do something with my life or die trying. There’s always someone who works harder, who deserves it more than you. You have to just accept that. Then, there’s some luck involved. And what we’re doing as a team is connecting. That’s the records, the production, the marketing, all of it. There’s something there that’s connecting to a wider group of people that don’t normally go to blues shows.

“I approached this album from the point of view that the world does not need another Joe Bonamassa record.”

You mention a “do or die” attitude. At one point, you were trapped in the blues barbecue joint circuit, before you worked your way out.

It always felt that way. The really magic moment for me was 2009 at the Albert Hall when Eric Clapton came out to play with me, and I will always be extremely grateful to him for that. But you realize that if that was May 5, the day after that show, May 6, we were broke. We had put all of our money in the DVD we made there. And when it came out, it did okay. And we had just enough money to keep the machine going and try to build. And then it hit PBS. And after PBS, life changed about six months later. But when you're watching somebody on a DVD seemingly have it all, sometimes the story behind the scenes is way different than the reality.

Getting back to Breakthrough, it’s an eclectic album, and you’ve been co-writing with some of the most respected songwriters in Nashville roots music, like Tom Hambridge, Gary Nicholson, Keb’ Mo’. And is there something of a personal breakthrough that sparked the title?

I think there is a meaning there. I’m trying not to repeat myself, but not abandon ship. The only thing I’ve abandoned is the notion that anything I’ll do will be pop music at all. I’m a niche guy. I don’t have a radio voice. I’m not looking to get invited to the Met Gala.

I’ve written a lot of songs for other people as well, like Jimmy Hall and Eric Gales. You’ve got to come in with some sort of idea, riff, or a title. A title is great because you can write something about that. A riff is like, “Okay, then what are we going to say?” Then you’ve just got to have a conversation and start riffing on it. You try to find a broader concept and try to make it something that’s personal to you that will also be personal to your co-writer and the audience.

It surprises me when I go into these old tracks, live, and people start applauding. I’m like, “I had no idea you guys even knew this song.” I just assume everything I put out over my life has not been a hit, and we’ve survived and navigated like that, almost like a jam band.”

I’m not looking for a hit. And I don’t want anything to do with that shit that’s coming out of Music Row. None of it. And I’m not looking for radio. So it’s, “Let’s have fun and write a six-minute banger, shall we? With a big fat guitar solo that has no chance of being played on the radio.”

“Any guitar that’s not in your normal comfort zone, just pretend it’s the only guitar you own.”

Speaking of big fat guitar solos, my favorite song on the album is “Broken Record.” I’m a sucker for a slow blues, and over its 7 minutes, it goes to a lot of interesting places and has a cool tonal palette. I even like small, nerdy things about it—like the way the delay hangs at the end of the song. How did you put the tonal palette together for that one?

I remember this: The solo that’s on there was basically a placeholder because I got the call to pick up my car at the shop. I’m at the console, dialed up a quick sound, get a call from the mechanic going, “Hey, your car’s ready.” I called the Uber, and as I’m waiting for the Uber to take me to get the car on a Friday afternoon, because I didn’t want to leave it over the weekend, I go, “Let me just give you a placeholder and I'll be back in a half hour.” I come back in a half hour and everybody’s going, “I think that solo’s good.” And I go, “Okay.” And it was literally just stream of consciousness. The whole song—vocals, everything—was done in an afternoon. And that’s the way I like to work. I like to cut in the morning, get the two or three that we’re gonna do that day, buy the band lunch, tell them to fuck off, then I’ll sing and play, and that’s it. You’re gonna sing, play, and once you’re happy, that’s it. If you’re prepared and know how to do it and hit the marks, three takes of vocals, we’ll comp it, done, move on. We’re at dinner by 6 o’clock. I learned that from Kevin Shirley. [The producer who’s frequently collaborated with Bonamassa since 2006’s You & Me and returns for Breakthrough.] You burn very intensely from about 10 a.m. to about 5:30 or 6, and that’s it. I’m not a night owl in the studio.

I want to talk to you a little bit about Journeyman Records, which is a pet project label of yours and your manager, Roy Weisman. What’s the impetus? What do you get from it personally?

We have Joanne Shaw Taylor and Robert John, and we’ve invested in those two because what we see in them is little glimpses of what was happening with me right before it hit. You’re a very talented artist, but if a tree falls in the woods and nobody’s there to hear it, does it sell any tickets? [laughs] No. I learned that. So we’ve created a vertical integration of business for those artists—everything from concert promotion to T-shirts to having ownership of their masters.

If I said to you 20 years ago that I do my own T-shirts, I do my own record company, and I promote my own shows, the notion, on Sunset Boulevard at the Chateau Marmont, would be, “This person clearly is not talented and has to do it by themselves because nobody will help them.” Now, the conversation taking place is, “My god, I gotta re-record my album because I don’t own my masters.”

So we’re using Journeyman Records as a proof of concept. It’s like, if I could do it, anybody can. It just takes hard work. And Vince Gill said it best: “If you don’t bet on yourself, how are you going to get anybody to bet on you?” And that’s so true. Maybe it’s ego, it’s bravado, it’s blind belief … whatever you want to call it. It is so important to have that chip on your shoulder before you even enter into this. Because if you don't believe in what you’re doing, you’re going to encounter some headwinds that may not be surmountable.

YouTube It

This performance from the Rudolf-Weber Arena in Oberhausen, Germany, is from April 29, 2025 and showcases Bonamassa’s range as an artist.