Music is the universal language

“Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace to those on whom his favor rests.” - Luke 2:14

General Interest

What Are Your Tubes Really Doing?

If you’ve never worked on a tube amp, it can be hard to find your way into understanding how they work. Somehow, we create a tiny signal by making metal strings on our guitars oscillate over a magnet wrapped with a coil of wire, and our amp takes that electrical signal and gets it to drive a speaker. (And driving the speaker is basically the opposite of how the signal started: It is a coil of wire moving within a magnet, which drives a speaker cone that moves air.) I’d like to simplify some of the processes that go on in our amps, so even if you’re not an expert, you’ll have some idea of what’s going on.

Let’s look at how tubes work and the role they play in turning our quiet, tiny guitar signals into sound. There are various types of vacuum tubes, but in the guitar amp world, three types are most common: rectifier tubes, preamp tubes, and power amp tubes.

Let’s start with rectifier tubes. As part of an amp’s power supply—the part of the amplifier circuit that makes the voltages the rest of the circuit needs to operate—rectifier tubes help convert, or “rectify,” the AC (alternating current) from the wall into DC (direct current). The amp’s power transformer only runs on AC, so it’s up to the rectifier tube to create DC, which is needed by the other tubes. (The filter capacitors are also part of the power supply, and these are needed to make proper DC from rectified AC, as well as a “choke” transformer.) The tubes that we use in this part of our amp are specialty tubes designed to do this one particular task and are not interchangeable with preamp and power amp tubes.

“The small guitar signal creates electrical movement on the screen of the tube, which causes movement on the plate, which gets significantly amplified due to its high-voltage potential.”

The preamp section’s job is to take the delicate signal from the guitar and amplify it to a level that can drive the output section. This is done in stages because of how small the guitar signal is, which is why we have many 12AX7-type tubes in our amps. Here’s how preamp tubes function:

Typically, V1 (valve 1—this is not a specific part on a schematic in this article but refers to the first tube the guitar signal encounters) will take that delicate guitar signal and amplify it by about 100 times before we do anything with it in the amp. This process repeats in the other preamp tube positions as well. How does a tube make a signal 100 times bigger? The V1 tube has about 300V DC on its plate (and a few volts on the cathode, but I don’t want to get too technical here and explain that—let’s just say that’s part of the operation of the tube). The small guitar signal creates electrical movement on the screen of the tube, which causes movement on the plate, which gets significantly amplified due to its high-voltage potential.

Because these are still small signals, the tubes are small. A 12AX7-type tube has two sections. In this case, V1 can also be used as a second gain stage or the first stage for another channel input of the amp.

Power tubes are bigger. There’s only a single stage inside the glass. Why? Because they do more work. They are the horsepower of the amplifier. They need to drive the output transformer, which pushes that speaker cone to move air. The overall function is the same but with a higher potential. In the power tube’s case, it’s usually 400–500V DC. More voltage means more power available. When we create electrical response on the power tubes with our signal, we get that analog response on the plates. Those plates are connected to an output transformer. The output transformer does what its name states by transforming the signal on the primary side (the power tube side) to what is on the secondary side, which is the speaker.

The power tubes need that high-voltage DC to operate, but a speaker only wants 10–30V AC to rock our world. The output transformer separates the AC guitar signal from the DC power supply. Again, there’s a bit more to this, but the power tubes are coupled to the speaker, driving that speaker and doing the hard work of moving air.

You might not be ready to go repair your amp, but hopefully, you now have a better idea of how your tubes work.

“When I played with Jason Newsted, I knew he was the one. Not that Robert Trujillo is a bad bass player, but Jason just has this edge”: In March 2003, Ozzy Osbourne introduced the world to his new bassist

Sus Chords, Arpeggio Embellishments, Minor 7 Barres, Humidity, Non-Diatonic Chords | Teaching Artist July Recap

“It was painful for me to listen to Ian Anderson’s voice. I felt for him a lot”: Dave Pegg on why he quit Jethro Tull, beating Metallica to a Grammy, gigging with John Bonham and working with Nick Drake in a smelly squat

“Car Bomb opened me up to playing bass with a pick. Now I’ve been a pick guy for so long I’m afraid to play fingerstyle!” Marrying savage hooks to technical prowess, Jon Modell is proof of just how heavy a 5-string bass can be in modern metal

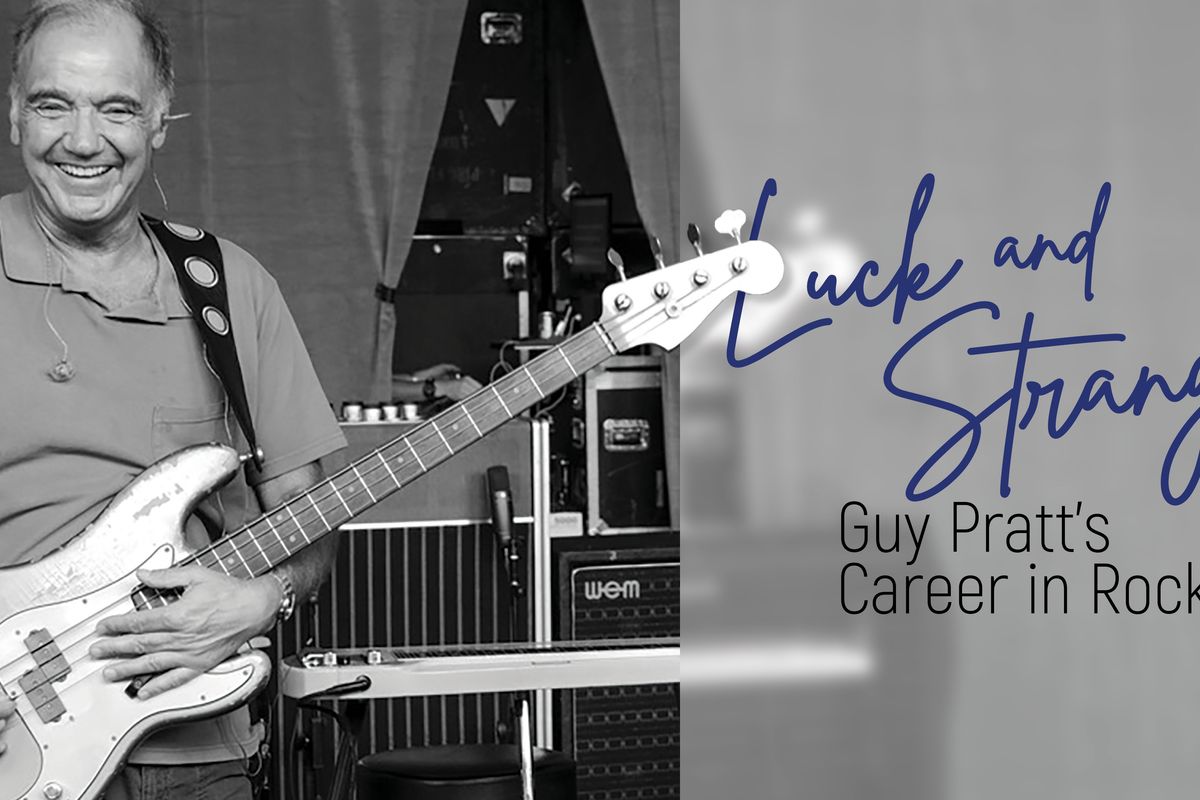

Luck and Strange: Bassist Guy Pratt’s Career in Rock

Over four decades, the Grammy-winning English bassist has held down the bottom for Roxy Music, Bryan Ferry, Pink Floyd, and David Gilmour. He’s recorded with everyone from Pete Townshend to Madonna and Michael Jackson, and he’s also a popular podcaster and stand-up comic. Whatever’s next, he’s ready.

If Guy Pratt’s name doesn’t resonate with you, his bass playing certainly has. He’s held the low end down for Pink Floyd and David Gilmour since 1987’s Momentary Lapse of Reason tour, and elsewhere in the Floydian universe he’s a member of Nick Mason’s Saucerful of Secrets, which specializes in the legendary band’s early music.

But wait, as the old huckster’s line goes, there’s more. Lots more. He’s also a longtime member of Roxy Music and Bryan Ferry’s band, and has toured with the Smiths. As part of the new wave band Icehouse in the early ’80s, he scored on the European and Australian charts and opened for David Bowie, and then springboarded into a series of higher profile gigs. In the studio, those have included sessions for recordings by Gary Moore, Michael Jackson (“Earth Song”), Tears for Fears, Echo & the Bunnymen, Iggy Pop, Tom Jones, Whitesnake, the Orb, Debbie Harry, Robbie Robertson, Madonna (“Like a Prayer”), and, in 2022, Pete Townshend. He also shared a Grammy for his playing on “Marooned” from Pink Floyd’s The Division Bell.

And yes, there’s still more. In addition to Pratt’s many TV, film, and theater scores, the amiable London native embarked on a sideline of stand-up comedy beginning in 2005, when he took his one-man-plus-bass show to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. That show, My Bass and Other Animals, spawned his book, and he’s toured two more original comedy productions since. In his spare time, he started a podcast, Rockontours, with Spandau Ballet’s Gary Kemp, a co-conspirator in the Saucerfull of Secrets band. Their famous guests, spinning tales of the musical life, have included Nick Mason, Bob Geldorf, Phil Manzanera, Trevor Horn, Chris Difford, and Adam Duritz over 213 episodes.

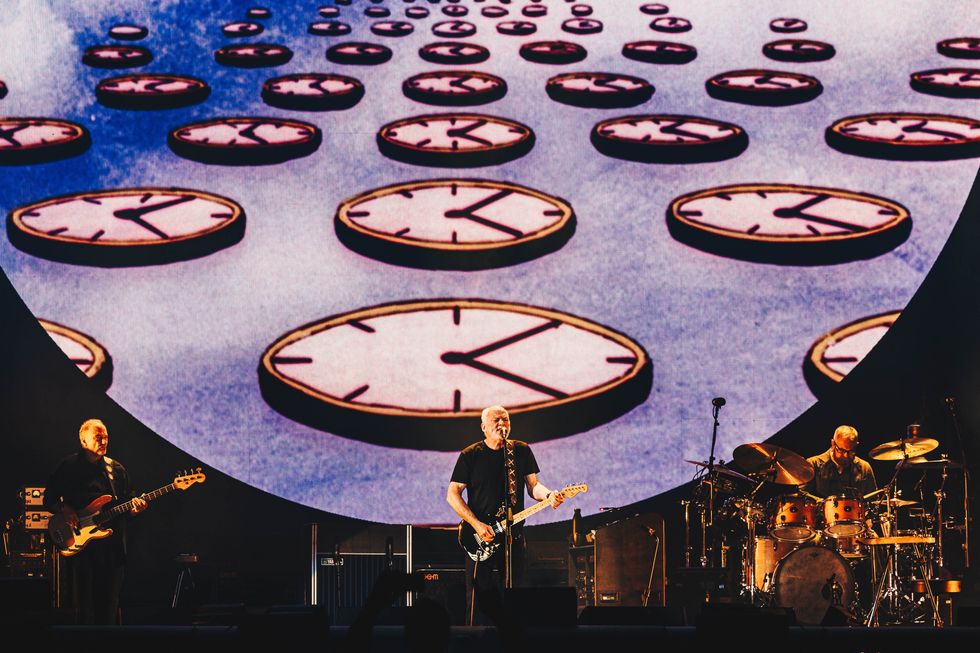

Last year, fortunate concertgoers got a chance to hear Pratt on Gilmour’s 21-concert, four-city tour behind Luck and Strange, an album where Pratt’s playing is woven into the deep currents that support the gorgeous tide of music created by the guitar giant and his hand-picked ensemble in the studio.

There’s an old saying among musicians that if you always want a gig, play bass or drums. Just before his teens, Pratt settled for bass. “I wanted an electric guitar,” he recalls. “I fell in love with electric guitar. Simple as that. I begged my parents, and of course mum said, ‘Oh darling, why don’t you get a nice Spanish guitar?’ ‘Spanish?! I’ll do that at school.’ Rock ’n’ roll was outside the school gates back then; it wasn't where we are now. And it had to be electric. The joke I would say is that actually a toaster would have been closer to what I was after than a Spanish guitar. So I asked for a bass. My mum and dad clubbed together and got me—because my birthday’s near Christmas—a bass guitar for Christmas and birthday. It was really weird … huge and kind of confusing, and I didn’t have an amp. But when I went back to school two weeks later, there were three kids who had got electric guitars for Christmas. Of course, if they wanted to be a band, they needed me, so I had my pick.” And so Pratt’s career began.

Guy Pratt’s Gear

Basses

- 1964 Fender Jazz Bass (named “Betsy”)

- 1960 Fender Jazz Bass (stack knob; present from David Gilmour)

- Nash Guitars T-style (w/ P- and J-bass pickups)

- Nash Guitars P-style

- Spector NS-2

- Lakland fretless bass

- Stratus 5-string

- Rickenbacker 4001V63 (w/ Nick Mason‘s Saucerful of Secrets)

- Rickenbacker 4003 (w/ Nick Mason‘s Saucerful of Secrets)

Amps

- Ashdown Guy Pratt Signature Interstellar-600

- Ashdown CL-10 cabs

Effects

- TC Electronic Hall of Fame

- Boss ODB-3 Bass Overdrive

- TC Electronic Subnup

- Ashdown Bass Graphic EQ

- Two Boss GEB-7 Bass Equalizers

- Boss DC-2w Dimension C

- Peterson Strobostomp HD

- Demeter Opto Compulator

- Custom Pedal Boards router

- Lehle volume pedal

- Ashdown footswitch

- Dunlop JCT95 Justin Chancellor Cry Baby Wah

- Dunlop volume pedal

- Boss Digital Delay DD-500

- Foxgear Echosex Baby

- Boss OC-Octave

- MXR Phase 90

- Origin Effects Cali76 bass compressor

- The Gig Rig QuarterMaster QMX-10

Strings & Picks

- Elites Stadium Series Roundwounds (.040–.100)

- Dunlop Tortex Triangle .88 mm (for older Pink Floyd songs)

I’ve been listening to your playing since the ’80s, when you started working with Bryan Ferry and with David Gilmour and Pink Floyd. Your tone has evolved over the decades, from what I would describe as a pointier sound.

Yeah, it was all front end. I was playing a Steinberger and it was bridge pickup. There was a lot of slapping. In the ’80s, bass was almost doing a different job because with a lot stuff I did there was a keyboard bass as well. Like when I used to work with [producer, drummer, and an original member of Duran Duran and the Lilac Time] Stephen Duffy, often I would go into the studio and I went on after the vocal. And my job was to kind of put stuff in the gaps, more like a horn part than bass.

It was the first drum-machine generation, and suddenly LinnDrums were everywhere. The bass wasn’t necessarily doing the job it had to do. You weren’t in the room with the drummer laying the thing down. With the birth of hip-hop and the new romantics and then bands like Simple Minds, everyone was coming from a quite funky perspective. There was a lot of stuff happening with technology and the bass responded really well to technology, with the Steinberger and various effects and amps. It felt like guitar was really taking a back seat at that time, too.

I mean, I was an asshole. Twenty-one-year-olds are assholes, aren’t they? So I guess the way I would look at it is I’m now a bass player. And maybe I needed the 40 years to become one. [laughs]

At what point do you feel like you made that transition?

I think it started on the ’94 Floyd tour. That’s when I suddenly started thinking, “Wait a minute, what are you doing here? You should be playing a Precision with a pick.” And then I kept at it. By 2006, the [David Gilmour] On an Island tour … I would say since then I’ve been a grown-up, if you will.“There’s no need for a sixteenth note on the bass anywhere in this music, ever.”

You’ve mentioned retooling your gear specifically to address that sort of deeper, more grown-up tone. And you’ve spoken about a particular instrument that you created—part Jazz Bass and part Hofner.

Bill Nash, who’s a friend and who makes the most beautiful guitars and basses, gave me a Telecaster bass. And it had one of those open [uncovered] pickups on it, but it also had a Jazz pickup. It’s got my Luck and Strange sticker on it, because it’s my Luck and Strange bass, and a stack knob. And the thing was, I was trying to think where to use it. On “The Piper’s Call,” David got ahold of the violin bass and noodled around, and it’s gorgeous stuff. I played a big, rounded Fender part that David told me to. Of course, when it came to rehearsing for the live shows, David said, “Well, obviously you’re doing both parts.” And I thought, “How the hell am I doing that?” Because there’s the Fender part and this nice little “do-do-do” going on top. I tried playing it with a violin bass. That just didn't work. It’s too small, just too insubstantial for me to hold. And it didn’t work on the Fender. So then I thought, “What would David do?” Because he’s really good at coming up with A-team-type solutions for things, like re-tuning his lap steel so he’s got a major and a minor chord. I was trying to think of a version of that, and I said, “Ah-ha! What if I take this Nash bass, and on the top strings, the D and the G, put on flatwounds, and then get a bit of foam and stick it under just the top two strings.”

What I always find interesting when rehearsing with David is what he remembers from bass parts. “You need to play that”—that sort of thing. A lot of the music is so slow and so big and there’s so much space in it. Very often it’s actually the length of the notes rather than how many notes you’re playing that matters more. With David, and this is something I get with the wisdom of years, every note does count. It’s quite funny when I think back to what I used to play in jams with him, like when we did a week of the Division Bell rehearsals. I was still stuck in that thing of playing sixteenth-note parts. It’s just like, “Why?” There’s no need for a sixteenth note on the bass anywhere in this music, ever.

Your career started, essentially, playing in new wave bands and on sessions, including Madonna’s “Like a Prayer.” But now you’re best known for your work with Pink Floyd, Bryan Ferry and Roxy Music, David Gilmour … more atmospheric music. What was that transition like for you?

There’s a quote: “As you live your life, it seems this absolutely chaotic, random set of events. And then when you get towards the end and you look back, it’s like the most beautifully plotted novel.” When I was playing with Icehouse, [frontman] Iva Davies wore his influences on his sleeve: Simple Minds, Bowie, Ferry, which was great stuff. I loved it. So I became versed in that style of playing. When we were making the second album, we got Rhett Davis, who was Roxy Music’s producer, for one of two reasons. Iva sang so much like Bryan Ferry that it was like, “If he’s gonna do Bryan, let’s do this properly.” Or Davis’ gonna go, “Come off it! Be yourself.” Anyway, it was fantastic working with him and we really got on. So it came to pass that I auditioned for Bryan and I got the gig. Even though I’d already worked with Robert Palmer, who was a huge, huge hero, this was different. Working for Bryan was crossing the Rubicon—as big as Bowie, an absolute icon in my head. So anything after that, Pink Floyd, nothing was gonna get bigger anymore. It was like, “This is Bryan fucking Ferry, you know?” Bryan is still my longest working relationship. I’ve been working with Bryan for 40 years.

“Something that I really noticed on the tour is it feels like David now owns his past. He’s not owned by it.”

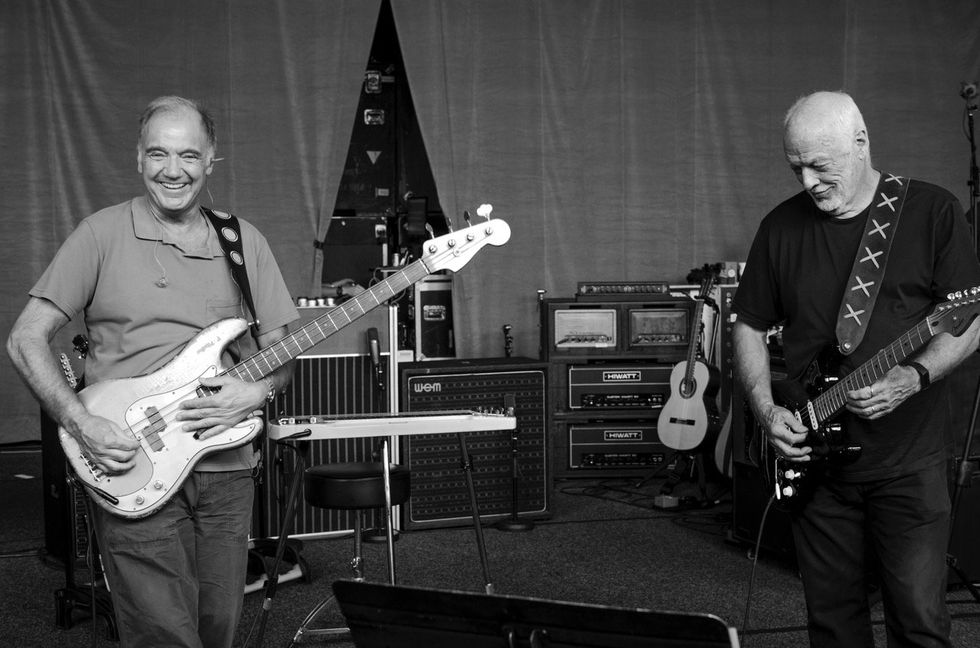

Focusing on David, who you’ve been working with for 38 years, did that relationship start after he played on Bryan Ferry’s Boys and Girls sessions?

The first thing was, I was playing for Dream Academy and David had produced them. He needed a support band for this one show in Birmingham. It’s quite funny because Nick Laird-Clowes, the main guy from Dream Academy, is this fantastic, enthusiastic character. And he said, “David’s heard your playing. He thinks you’re amazing. He can’t wait to meet you”—which of course was just bollocks. So we get up there in Birmingham. I’m terrified. And he said, “David’s just dying to meet you.” And I went in and just stood in his dressing room and it was awful. We both stood there with nothing to say until one of us had to walk away. David, being the ranking officer, got to be the one who walked away. And that was the end of it. But I got to spend a bit of time with him with Bryan, which sort of loosened things up a bit. And I started just seeing him out and about. I think I was just getting invited to better parties. [laughs]

So, I went on holiday to Thailand and I came back and there’s all these messages from David. The first one saying hi, he was doing an Amnesty International concert, the Secret Policeman’s Ball, and he wanted me to play with him and Kate Bush. And there’s another message and another message. “Hi Guy, just wondered, it’s next week you know.” And then, of course, he had to get someone else. I’m like, “My god, that was my one shot.”

A while later, David, Rick [Floyd keyboardist Richard Wright], and Nick were saying they were doing a new Pink Floyd album, and I didn’t think any more about it until I got a phone call from L.A., and it’s David going, “Hi. We’re putting Pink Floyd back together.” He said, the tour was gonna be a year, and would I be interested and available? So I went, “Yes!” And he said, “Oh, not working much, then?” And that started our relationship of him ribbing me and me constantly falling for it. That’s been the hallmark of our relationship for the last 38 years.David’s latest solo album, Luck and Strange, seems perhaps more organic than most of the Pink Floyd albums he’s helmed and his earlier solo work. After all these years working with him, you’re in a good position to comment on that. Is there something different that you find within it?

I know what you mean. There’s definitely been something different about this album, about the way it’s been received, about the tour. It was hugely successful in a way that some people’s solo records could only dream of. On An Island is where it started. There are quite a few people now who will point to the song “On An Island”’s solo as on a par with “Comfortably Numb.” But there’s something about this one, a sound. And a lot of that’s to do with Charlie Andrew and Matt Glasbey's engineering. It feels of a piece. And something that I really noticed on the tour is it feels like David now owns his past. He’s not owned by it. And for me, if you look at the set list, well over half is songs I played on. It’s always been quite piecemeal with David’s other records. I’ve gone in for a couple of days here and there, but David’s played quite a lot of bass himself. He’s brilliant.

With David, there is always this thing where suddenly he’s puttering about, then puttering about a bit more, and then suddenly “bam,” we’re in gear—there’s an album. We did a whole week in British Grove Studios with Steve Gadd, which was amazing. His playing wounds you, gets you in the chest. It’s so light and so potent. It’s just gorgeous. Why I think he was such a great call is that, in all my years with all those elite drummers, Steve is the closest to Nick.

I think Nick is a vastly underappreciated drummer. I love his playing. It’s so conversational.

That’s a great way of putting it. Yes, he absolutely was underappreciated, in the same way, if you remember years ago, that David was actually a somewhat underrated guitarist. And you know, I’ve noticed that with all the top drummers I talk to now, everyone’s like, “Nick Mason, man!” It seems like he can take his playing anywhere he wants to and feel utterly relaxed at the same time. And what’s been amazing with the Saucers, because we’re doing all that early stuff, is it’s so crazy, manic. I get worried for him, you know. “Should someone have a heart monitor on him or something?” But that stuff doesn’t seem to bother him at all. It’s fantastic.

I need to ask, what was it like playing onstage in Pompeii? A beautiful setting; what an extraordinary experience.

At the risk of sounding unbearably smug. I’m one of the small group of people that played Pompeii twice. With David, we were on a stage at the end of the amphitheater. It was so small, we just had the screen, there was no sides, there was no roof; it was mad. There was only 1,800 people, so it was like a club gig. It was fantastic. And with the Saucers, we played at the Teatro, which is the theater, which is really small but lovely, in a different part of the complex, but it’s still Pompeii. But we did it in the middle of an absolutely horrendous heatwave. So it was nearly 40 degrees [104 Fahrenheit] and we couldn’t sound check. The poor crew were wilting and we basically just had to sit on the bus and then went in through the audience, did the show, and left. Whereas with David, we had Mary Beard, the great historian with us. We were there for four days.

“At the risk of sounding unbearably smug, I’m one of the small group of people that have played Pompeii twice.”

You’ve done extensive film and television work. How did you get into that?

I love working on film. I used to work with Michael Kamen a lot. I love working to picture. I also love that it is a great way of writing music and not having to finish it. Usually, you come up with a great piece of music and, okay, well now I need a verse, now I need a bridge. Whereas with a film score, it’s like this character needs something. That’s it. Then you move on. TV music is like the demo version of film music. No one expects a real orchestra, so you’re kind of going, if this was a film, the music would be doing this. Of course, now everyone’s got massive screens and 5.1, so the stakes are higher.

That came about through me hanging about at the Groucho Club, which is this big media arts club in London, and just telling people I wanted to do film music. The first thing I did was a documentary … on the Roswell autopsy. That was completely fake, but it was perfect. This was was mid-’90s, so it was the whole electronica and ambient house, chill, Orb scene. So perfect for that sort of film. But then I got this fantastic gig, which I’m still really proud of, which is this TV series, Spaced, with the director Edgar Wright, with Simon Pegg and Nick Frost starring in it. Edgar, if you know from his films, is such a film nerd, so literally everything is a reference. It was brilliant. I had to do Kubrick. There’s a bit of what looks like a zombie movie, so I had to kind of write a John Carpenter score.

You’re also a podcaster, and your Rockonteurs, with Gary Kemp, is very entertaining, with its “behind the music” approach

The podcast came about literally from the first Saucer Full of Secrets tour. We had this tour bus and this is long enough ago that the bus actually had a DVD player. And I brought a box set of The Old Grey Whistle Test, which is the legendary 1970s English music TV show. We used to watch it on the bus, and it was just brilliant. Everyone had an opinion about every act that was on, or a story. Of course, half the time Nick knew them and he’d have some great stories and we’d be talking about it, and someone said, “Man, we should do a podcast.”

We didn’t know it was gonna fly at all. We had this address book, we just asked a few mates to come and do it. And it just became a thing, you know, and it’s really nice because no matter how well I know the artists, we always get something I’ve never heard. We had a couple of scoops. My favorite got on the front page of The Times and The Guardian, when Whispering Bob Harris, who used to present The Old Grey Whistle Test, told us that Nixon asked Elvis to spy on John Lennon.“All musicians have really funny stories because it’s a kind of preposterous life we lead.”

You also do a one man bass-and-jokes comedy shows?

All musicians have really funny stories because it’s a kind of preposterous life we lead. So I started telling them, with my bass in hand, and it did really well. So then I had to write a book [My Bass and Other Animals]. I went around the world with it, been to Australia four times.

It’s something I really like, because I knew I was never going to do a solo musical thing. I really love the job of the bass. I mean, I’m very happy being the center of attention at a table or whatever. But in a musical set, I really love that thing of playing the instrument that just makes everyone else work. But there’s a syndrome I call “sideman bitterness” that I’ve seen happen a lot. When people start getting to their 50s or whatever, it’s like, “Where’s my shit?” And so I thought, “Well, I need to do something on my own to avoid that.”

Another thing is that when you get up on stage with Bryan Ferry and play “Love Is the Drug,” you’ve got a pretty good idea of how it’s going to go. With David Gilmour, when you play “Wish You Were Here,” you’ve got a pretty good idea of it. What I love with stand-up is that I get up there and people don’t really know what I’m gonna do. They don’t really know what they’ve come to see. I’m not entirely sure about it. It’s completely fresh, in the moment. And I think that’s something that might have made me a better bass player, in a way. Because now I’ve had it all on my shoulders, so it’s really nice to go back and just be the guy playing bass.YouTube It

David Gilmour is Guy Pratt and Gary Kemp’s guest on this episode of the Rockonteurs podcast.

Think Like a Drummer

I recently published my book Creative Rhythms for Melodic Instruments or Think Like a Drummer, and I’m delighted to say it has been met with great enthusiasm by players and educators. The premise is simple: Take some of the most iconic drummers—from all genres—and use “in-the-style-of” drum fills as source material for melodic phrases, all in a variety of scale and arpeggio patterns, as well as multiple keys.

In addition to the notation, I also released audio examples in a call-and-response manner, allowing musicians to play along with the melodic phrases, with the isolated drums, or respond to the phrases with their own ideas. (Note: The audio for the book features drums and piano, as the book is available in several versions: guitar tab, bass tab, treble clef, bass clef, Bb instruments, and Eb instruments. Nevertheless, for this lesson I have specifically recorded electric guitar.) I also want to point out that the examples in this lesson are not duplicates from the book, but rather, as the book encourages, creative variations.

Icons of the Drum Kit

As I wrote in my book’s introduction, there are countless phenomenal drummers absent from my examples. I can name at least two dozen more drummers I wish were included (in fact … I’m working on Vol. 2). So let’s not nitpick as to who’s the best drummer, let’s just start playing: In the style of …

Ex. 1

Ringo Starr

It is unnecessary to rehash how underrated Ringo is. Instead, listen to the third verse of “Hello, Goodbye,” “A Day in the Life,” or any of the Live at the BBC recordings. Ringo has style! Ex. 1 is a Ringo-style fill, with lots of space (drummers, it’s okay to rest), and features both descending D Dorian and C major scales. (Remember, D Dorian is just C major starting on D.) Emphasize those rests, people!

Ex. 2

Bill Ward (Black Sabbath)

Of all the drummers in my book, I think Bill Ward’s fills are the most recognizable. Bill has distinct flair and an overlooked swing feel. To honor Black Sabbath in general, Ex. 2 features E minor pentatonic and E harmonic minor, played in descending groups of three. That’s down three notes, back one, and down three from there. Groups of three is a rather cliché move, still, when you add a unique rhythm—as demonstrated here—the pattern takes on new life.

Ex. 3

Neil Peart

What more needs to be written about Peart? Or Rush in general? Nothing. Legends. The end. Ex. 3 is based on one of Peart’s most iconic fills (you’ll guess it.) and uses A Phrygian dominant, in two octaves, in homage to Alex Lifeson’s solo on “YYZ.”

Ex. 4

Richard Bailey

Bailey is arguably the least well-known drummer in my book, but I guarantee, if you love guitar music, you know his playing. Bailey is the drummer on Jeff Beck’s Blow by Blow (and many other albums and singles). Ex. 4 is the first to showcase arpeggios, in this instance, F#7 to Emaj7, implying an F# Mixolydian sound, from the home key of B, emphasizing the V chord. Think “Freeway Jam.” One thing that makes these rhythms unique are the ties from the “and” of 1 to the 2, as well as the tie from the “a” of 2 to the 3. This is tricky!

Ex. 5

Stewart Copeland

One of my favorite things about Copeland is that he rarely played the same thing two nights in a row. I highly recommend listening to live recordings from the 1979–1980 Reggatta de Blanc tour, particularly the breakdown section (after the guitar solo) of “So Lonely.” Consistently brilliant and incomparable. They might have been the best band in the world on that tour. Ex. 5 provides us with a Copeland-esque fill (note that grace note on beat 4) and a C#m pentatonic lick with bends and pull-offs, à la “Message in a Bottle.” If you’ve never paid attention to Andy Summers’ fills in that song, do so. He’s more B.B. King than “King of Pain” on that one.

Ex. 6

Chester Thompson

It’s difficult to know who Thompson is most famous for playing with, Weather Report, Santana, Genesis, or, for my money, Frank Zappa. Thompson’s tenure with Zappa allowed him to truly experiment with rhythm. Listen to “Approximate” on You Can’t Do That on Stage Anymore, Vol. 2 The Helsinki Concert. Ex. 6, in keeping with Zappa’s penchant for two-chord jams, demonstrates more arpeggios, F7 to Gm7, in the home key of Bb major. In this one-measure phrase, we have eighth-notes, dotted-eighths, 16th-notes, and 32nd-notes. This should test your rhythmic abilities.

The final two examples feature drummers who are not in my book, so I’m happy to share them here: John Bonham (of Led Zeppelin) and Carlton Barrett (of Bob Marley and the Wailers).

Ex. 7

John Bonham

No, I’m not highlighting Bonham kick drum triplets. Rather, Ex. 7 features a Bonham snare/floor tom/kick drum combination. And the phrase I created also pays homage to his bandmate Jimmy Page, with an A blues riff, modulating to C blues (name that tune!) that includes more guitaristic phrasing.

Carlton Barrett

While Bob Marley might be the face of reggae, Carlton Barrett, along with his brother, Aston, on bass, may be the defining sound of reggae, as the brother duo played on countless Marley recordings and live performances. While Ex. 8 does not include a “one drop” (look it up, or just listen to “One Drop” by the Wailers), it is still quintessential Barrett. The melodic phrase is built with ascending arpeggios, Dmaj7 and Gmaj7, the I to IV chords, in two different patterns and positions.

Infinite Rhythmic Combinations

Besides the fact that I enjoy playing the examples myself, one of the reasons I wrote my book is because I believe rhythm is the most important feature in music, and yet it is underutilized. While these examples demonstrate quite a bit of variety, the fact of the matter is, rhythmic combinations are infinite. I encourage you to studiously experiment with uncommon phrasing. Intuition is great, but eventually, in my experience, it becomes unconsciously repetitive. So sit down and really work on distinctive rhythmic phrases. I promise you, you will never run out of new ones.

“The scene was super-underground. When the music industry developed, everyone got excited to start a band”: Meet Seera, Saudi Arabia’s first public all-female band, who are merging Nirvana and Tool with Arabic influences – and going global

“Those tubes need to be burning. As I put it to the band, I like to smell dinner cooking”: With his gourmet phrasing and R&B hot sauce, D.K. Harrell is the blues hero you need in your life right now

Met Museum refutes that former Rolling Stones guitarist Mick Taylor ever owned the ’59 Les Paul he claims was stolen from him – and now appears in a new exhibit

“I sat down and wrote it out as one word – and dropped the ‘A’ out”: Early Megadeth guitarist claims he came up with band’s name – here’s his account

Who came up with the name Megadeth? There are different accounts, including from frontman Dave Mustaine, who in his 2010 book Mustaine: A Heavy Metal Memoir, claimed short-lived vocalist Lawrence “Lor” Kane coined it. “Lor knew I had already written a song entitled Megadeth [Set the World Afire] and thought it would work equally well as a band name,” he wrote.

But now, guitarist Greg Handevidt – who was in Megadeth briefly in 1983 – claims it was actually his idea. He drops the revelation in a new guest appearance on The David Ellefson Show, hosted, of course, by the band’s former bassist.

“We were sitting down in our little apartment, and Dave had read a pamphlet by Senator Alan Cranston talking about the ‘arsenals of megadeath’, and I think that really triggered something in him about nuclear war and just how devastating it was and everything,” Handevidt says [via Blabbermouth].

“And I remember thinking, ‘Holy shit, the arsenals of megadeath.’ And he had that line in the lyrics. And it just occurred to me, ‘Megadeath.’ I’m, like, ‘That would be a cool name for a band.’”

But after some contemplation, Handevidt thought to himself: “‘Do you really want the word ‘death’ in the name of your band? Do you really want that?’ It seemed kind of negative-karma-ey to me back then; that’s what sort of was in my head.”

Rather than scrapping the idea, he says he came up with a subtle tweak: “I sat down and I just wrote it out as one word and I dropped the ‘A’ out, and I just wrote it on a piece of paper and I was, like, ‘I think this is cool. We could call the band Megadeth. One word. We take out the ‘A’. It’s unique. It doesn’t have any sort of dark connotation around it. And I think people would see it and not be put off. It wouldn’t put people off.’”

He also cites commercial reasons for dropping the ‘A’, saying that people were just not ready at the time for extreme band names:

“And I think at that point in time to break through in a commercial sense without just completely selling yourself out, I think there were barriers that would’ve… I’m not sure Capitol Records was ready to sign a band called ‘Death’ at the time. And maybe, maybe not.”

Mustaine, Handevidt goes on to say, did not agree to using the name immediately, but warmed to over a couple of days: “He came back and he was like, ‘Yeah, you know, this is growing on me.’”

The post “I sat down and wrote it out as one word – and dropped the ‘A’ out”: Early Megadeth guitarist claims he came up with band’s name – here’s his account appeared first on Guitar.com | All Things Guitar.

A Mysteriously Excellent Kay Effector

Guitar players today don’t know how good they have it. Inexpensive guitars imported from outside the U.S. are widely available, dependable, and high quality for the price. Folks in the ’60s and ’70s weren’t so lucky. Most instruments made at beginner-friendly price points by brands like Harmony and Kay were inferior to the Martins and Gibsons they copied, but a top-of-the-line Harmony had high-end features. Once you started looking at models with fancy inlays and multiple pickups, some cost even more than low-end and mid-priced Gibsons.

As the popularity of the guitar soared, so did the demand for even cheaper options. Harmony and Kay couldn’t keep up, and American importers noticed an opportunity in Japan. But as the yen gained strength, importers started looking for even lower-cost manufacturing and found it in Korea.

A young company called Samick sprang into action. Originally an importer of Baldwin pianos, they rapidly expanded their production capabilities with a factory able to make one-million instruments per year. Great news for American importers, but perhaps less great news for American guitar beginners. The market was soon flooded with Korean guitars still in their trial-and-error era. Truss rods were non-adjustable decoration. The finishes were no match for the heat and humidity of container ships. Hardware made from cheap die-cast aluminum was prone to snapping in half. Needless to say, early Korean guitars developed a bad reputation.

So when this Samick-made Les Paul copy came through the doors of Fanny’s House of Music, expectations were low. The floppy-looking bolt-on neck and blank headstock trigger a trauma response in guitarists of a certain age. But once you try it, all the bad experiences melt away like so much nitrocellulose on a container ship. The action is extremely low at 2/32", but it somehow still has “resistance” that feels so good—the kind that lets you dig in and get a different sound. The frets are worn but well cared for. Whoever used to own this beauty didn’t let it go too long without a crowning.

“Everything about it, we were like, ‘Wait, this shouldn’t be this good!’” Fanny’s owner Pamela Cole says, with a laugh.

Kay went under in the late ’60s, and its assets were auctioned off in 1969. The rights to the name were acquired by an importer called Weiss Musical Instruments, whose primary brand was Teisco del Ray. Calling their guitars “Kay” gave them more credibility with dealers, even if the guitars were essentially Teisco del Reys with a different name on the headstock. They certainly didn’t resemble the old Kays one bit.

“The hardest thing about adding a 3-way switch would be finding the real estate.”

In the Sears catalogue, this model was called the Kay Effector. Its flight-deck-esque array of switches and knobs sits atop a spaghetti plate of cables and components. There are two single-coil pickups in humbucker-sized housing, which are both always on. There’s no pickup selector. Intrepid modders take note: The hardest thing about adding a 3-way switch would be finding the real estate. Included in the flock of switches are one that flips the pickups out of phase (hip!) and one that turns the built-in effects on and off.

Only one of the Effector’s effects feels familiar: The fuzz has a Muff-like quality but is more of a distortion than a fuzz. The four modulation effects—echo, tremolo, wah, and the intriguingly-named “whirl wind”—sound similar once you start playing around with them. A poke around the schematic reveals why: All the modulation effects work off the same 2N2646 unijunction transistor, which mega-nerds may recognize from the classic Vox Repeat Percussion. In fact, each modulation effect is the same, hitting different capacitors along the way to give each one a subtly different sound. This author enjoyed “whirl wind” the best, partly because it had the most fun name, but also because it had a dynamic, “reverse-sawtooth” feel.

Guitars like this Samick-made Kay Effector are artifacts from a transitional moment in gear history, when manufacturers were learning on the job and players were beta testers. A guitar that once felt like a compromise now feels like a hidden gem. It’s a reminder that innovation and excellence don’t always come from the top shelf. Perhaps the weirdest instruments are some of the best; they just never had a chance to be taken seriously.

“No one needs an exact copy”: Should guitar covers sound exactly like the original? Dweezil Zappa thinks so – but I’m not so sure. So I asked you what you thought

There’s never been more guitar content creators, and many of them dabble in covers to help get their chops seen by the world. But when it comes to such covers, how important is it that they remain faithful to the original songs?

It’s a debate that was kicked up earlier this week, when guitarist Dweezil Zappa – who also happens to be the son of late legend Frank Zappa – expressed his opinion that those who cut corners when covering classic songs exhibit “laziness”.

“There’s a lot of people that – and sometimes it just comes down to laziness – they’re like, ‘Well, I’ll just do my own thing.’ Because they hear enough of it, and they’re like, ‘I’m in the ballpark. I’ll just make my [own thing],’” he said.

“But to me, when I was learning songs, if it was Van Halen or if it was something that Randy Rhoads was playing, I didn’t feel like I was playing the song at all unless I played exactly what I heard them doing. And I wanted to learn the nuances. I wanted to try to get the sound. I wanted to do that. Because to me, that was the whole package of playing the song.”

Now, when I saw these comments, I couldn’t help but think, ‘Does it really matter?’ and ‘Isn’t the point of art interpretation, anyway?’ Perhaps it’s because I’ve dabbled extensively in online guitar covers myself, and that’s my bias – or even “laziness”, to indulge Zappa – talking.

But in any case, I thought I’d put the question out to you, our wonderful Guitar.com audience via social media, to see how much it really matters that guitar covers emulate the style and sound of the original tracks, or whether anyone really cares at all.

To my pleasure, the comments largely took a pretty measured approach to the whole debate.

“Short answer: Yes. Longer answer: Either nail it or do your own thing, anything in-between comes across as slipshod, half-assed, and lazy…” writes one user.

I can’t help but feel that there’s no point in creating a cover that’s exactly like the original, because why would someone listen to that when they can just listen to the original? And it seems to be a view many share.

“No one needs an exact copy cover that’s just the original with different vocals,” another person writes. “Take a spin on it!”

“Technique is overrated and emulation destroys creativity,” writes another. “It has been shown that most interesting artists in the past 30 years were not the most technical but someone that actually has something to say. Music is communication.”

“I’d rather see artists make it their own,” says another. “If vocalists could emulate the voice exactly, would he want that too? what would be the point? It’s already been done that way.”

“I absolutely hate hearing a cover song done by another band that sounds like a perfect copy of the original,” says another. “It’s not a tribute, it’s just a copy. Change the tempo, sing it differently. Make it minor. Make it exciting!”

Other commenters note that the difference between a cover version and an original is similar to that between a studio recording and a live version. Is there any point in going to see a band or guitarist live if it sounds exactly like the album version?

“Many guitarists like Ritchie Blackmore, Jimmy Page etc always improvised when playing their solos live, so why shouldn’t other people when covering famous songs?” one person astutely notices.

“I am even bored when bands reproduce their own music live note for note…” another writes.

Perhaps an important distinction needs to be made between a dedicated tribute band – who might need to more accurately recreate the music of the artist they’re emulating – and an original artist creating a cover.

“If you’re in a wedding covers band, yeah absolutely agree [with Dweezil], if you’re an original artist covering a song you should put your own spin on it, otherwise what’s the fucking point?” says another.

Ultimately, no one’s holding a gun to any of our heads – I hope. At the end of the day it doesn’t really matter. If you get your kicks from studying and emulating a song exactly as it was recorded, then why not. But if you’d rather let the creativity flow and make it your own, who’s gonna stop you.

No one’s going to force anyone to listen to anything either, but it’s certainly an interesting conversation, especially amid the increasingly content creator-heavy online landscape.

The take away from all of this? Play – and listen – to whatever the hell you want. Thanks for coming to my talk.

The post “No one needs an exact copy”: Should guitar covers sound exactly like the original? Dweezil Zappa thinks so – but I’m not so sure. So I asked you what you thought appeared first on Guitar.com | All Things Guitar.

Reverend Guitars Launches Bold New Spacehawk Supreme

Three pickups, seven combinations, endless sonic options

Reverend has unveiled the Reeves Gabrels Spacehawk Supreme, the latest version of the innovative Reeves Gabrels Spacehawk.

Reverend has unveiled the Reeves Gabrels Spacehawk Supreme, the latest version of the innovative Reeves Gabrels Spacehawk.

The new model sports three Railhammer pickups: an Alnico Grande at the bridge, a Hyper Vintage in the middle position, and a Hyper Vintage at the neck. Packed with features, the Spacehawk Supreme offers a bevy of switching options to supplement its 5-way pickup selector. The Reverend Studio Switch adds the bridge pickup (push-pull volume knob) allowing a total of seven pickup combinations, plus the guitar provides a push-pull phase switch in the tone knob. Last, but not least, the guitar features a kill toggle for instant on-off.

Sporting a Bigsby tremolo, the Spacehawk Supreme is available in two eye-grabbing finishes: Metallic Silver Freeze or Venetian Gold.

The Reverend Spacehawk is the guitar that Reverend Guitars designed for Reeves Gabrels when he joined The Cure. It is the sixth signature model for Gabrels from Reverend Guitars.

Reverend’s new Reeves Gabrels Spacehawk Supreme carries a street price of $1699. For more information visit reverendguitars.com.