Music is the universal language

“Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace to those on whom his favor rests.” - Luke 2:14

General Interest

“Nuno Bettencourt isn’t the only one keeping Eddie Van Halen’s fire burning – the most underrated guitarist on the planet just gave him a run for his money”: July 2025 Guitar World Editors' Picks

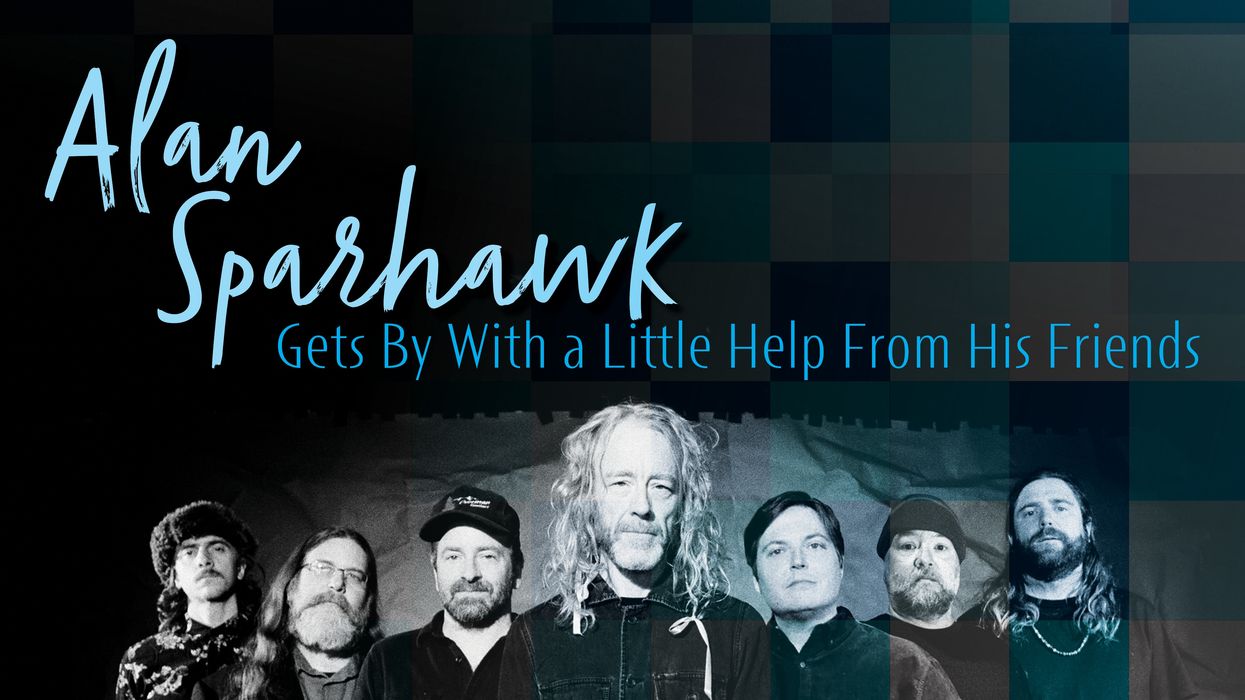

Alan Sparhawk Gets By With a Little Help From His Friends

Alan Sparhawk has been a friend of Trampled By Turtles for a long time. Both parties came up in Duluth, Minnesota, and Low—Sparhawk’s often ethereal slowcore band with his wife, Mimi Parker, who died from ovarian cancer in late 2022—took Trampled By Turtles out on the road very early in the latter’s career. But few would’ve expected a studio collaboration between Sparhawk and the bluegrass merchants.

With Trampled By Turtles makes one wonder why. The record is deeply moving, often pulsing with powerful forward momentum, driven by Sparhawk’s unadorned voice like a herald calling out that something heavy this way comes. Of course, it arrives—especially in the bruised ecstasy of “Screaming Song” and the mournful “Don’t Take Your Light.”

“Some of the songs are the first things that fell out of me in response to loss and grief,” Sparhawk says over the phone from the Quad Cities, on tour with Circuit des Yeux. “Some of them are pretty pointed, and I really felt the duty to do those songs justice, to honor them for what they were and what they came from. White Roses, My God was literally just my head exploding and me running away from the guitar and from my voice and trying to figure out some way to let this explosion out of my skull, this screaming, you know? And this thing with the Turtles is the first breath.”

The two albums were recorded around the same time—even sharing the songs “Heaven” and “Get Still”—but they’re polar opposites, sonically. White Roses, My God trades in all-encompassing electronic soundscapes and so much vocal modulation that Sparhawk is unrecognizable, while With Trampled By Turtles feels stripped down, and features his voice rising clear above the bluegrass group’s earthy, mostly acoustic string work.

“It’s this unified wall of strings coming at you,” Sparhawk says about Trampled By Turtles. “There’s something egoless about the way they play together and the way they make sound. It doesn’t get broken down the same way a lot of bluegrass ensembles approach things.”

“I remember being still pretty scared and uncomfortable with my voice after years of singing with Mim and from the loss in general.”

After Parker died, Trampled By Turtles extended Sparhawk an invitation to hit the road for a few dates with them, an experience that brought the two closer and planted a seed that bloomed in Cannon Falls, Minnesota, in the winter of 2023. Sparhawk came in at the tail end of a Trampled By Turtles recording session there with a handful of songs, some old, some new, and the album came together swiftly. The result is a recording that foregrounds feeling, naturality, and spontaneity—more a pouring out than a piecing together. It’s often jarring how bare Sparhawk’s voice is, akin to an exposed nerve. It sounds more than a bit like a leap of faith, and he mentions that his only skill is diving into the unknown. “I’m quick to jump off the cliff,” he says.

“I remember being still pretty scared and uncomfortable with my voice after years of singing with Mim and from the loss in general,” Sparhawk says. “It really was making me feel very, very lost and awkward, singing. And I think during this Turtles thing—because this opportunity had come up and these guys had been so friendly and gracious with me—I consciously remember having to go, like, ‘I know I’m still not comfortable hearing my voice right now, but I have to just trust. I have to trust that this is what I can do, that I can sing, and that I’ve been working hard on this all my life. For the sake of the moment, put aside my confusion, and just trust that maybe five or six months down the line, I’ll be able to look back and decide whether I was comfortable with it or not.’ And honestly, it helped.”

“When I was a teenager, I remember very specifically saying that I like the guitar, and I really wanted to take it seriously, and I made a pact with myself to play it every day.”

It also marks a coming back to guitar for Sparhawk, the instrument that remains his “main physical connection to music.” But one needs to get away to come back. He thrives off of switching things up, much more able to see the big picture when he’s thrown into situations where he’s doing different things and forced to look at music differently. He says he struggles with the guitar, and has to practice often to stay fluent with what he wants to do. An opportunity to ponder something he hasn’t pondered, or play in a way that he hasn’t quite had to before, is always positive for him.

“I’ve always insisted on playing every day,” Sparhawk says. “When I was a teenager, I remember very specifically saying that I like the guitar, and I really wanted to take it seriously, and I made a pact with myself to play it every day. So it’s always there. It’s a world in my brain that I feel pretty happy in. But at the same time, I have to constantly be engaged with it to keep my footing there.”

Alan Sparhawk’s Gear

Guitars

1960s Danelectro Convertible

1970s Gibson Hummingbird

Amps

1960s Silvertone amp

Fender Pro Junior (small stages)

Fender Twin (large stages)

Effects

Chase Bliss Onward

Chase Bliss Mood

Red Panda Tensor

ZVEX Octane 3

ZVEX Box of Rock

Boss synth pedal

Tech 21 Double Drive

Strings

D’Addario strings (.011-.056)

His own approach to music-making and his musical community seems to be providing plenty of opportunity for challenges; the doomy goth-rock of Circuit Des Yeux sounds worlds apart from With Trampled By Turtles, which sounds worlds apart from White Roses, My God. And yet, it all exists in Sparhawk’s musical world—a world he says he feels blessed and grateful to be in, one that fascinated him as a child and that he wanted to be a part of. It’s given back in spades, too. Low, of course, was a family affair, and so is this new record, on which Sparhawk’s daughter, Hollis, also sings, during the chorus of “Not Broken.” One gets the feeling that connection has always been the point.

“Anyone who’s been blessed with friends that are there for them when they’ve had losses—those are the most important things in life,” Sparhawk says. “I think music is there to remind us of that, and give us a really amazing opportunity to feel that with each other and to bless each other.”

YouTube

Lose yourself in this peaceful, psychedelic rendering of “Get Still,” off of With Trampled by Turtles.

“You don't come into a Van Halen record and tell Eddie, ‘This is how we're going to do it’”: Why Eddie Van Halen didn’t double-track his guitars

When Dave Grohl Used an Amp in a Gas Can to Make Foo Fighters’ Lo-Fi Debut

This year, the Foo Fighters’ self-titled debut turns 30 years old. As a nearly obsessed fan of the band since 2011’s Wasting Light, I’ve developed an exceptionally strong attachment to the first album. By now, we all know the story: Following the tragic and sudden end of Nirvana, Dave Grohl found himself searching for the right way to start making music again. In October 1994, he booked a week at Robert Lang Studios in Seattle, Washington, with producer Barrett Jones, and they got to work recording what would become the debut Foo Fighters album. This release would serve as the foundation for the band’s tenure at the forefront of modern rock for decades to come.

There is something uniquely nostalgic and spontaneous about the sound of Foo Fighters. The crunchy guitars and uptempo beats are straight off the heels of the grunge movement, with elements of punk and metal—staples of Grohl’s musical influences growing up—plus a sweet, melancholy shoegaze vibe, which permeates songs like “Floaty” and “X-Static.” These recordings are lo-fi, but still deliberate and precise, a testament to both Grohl’s skill as a musician as well as the limited session time allotted to complete the album.

The gear used to record this album has always been an intriguing mystery to me, and one piece specifically kept popping up in my research: an amp known as the Can. Over the years, both Grohl and Jones have cryptically mentioned a mythical amplifier that provided the most glorious, disgustingly raunchy fuzz tones, heard most notably on closing track “Exhausted.” For a long time, fans online talked about a “gas-can amp,” an “oil-can amp,” or even some claiming the effect was achieved by placing a microphone into a metal can next to a guitar amp—nobody was quite sure what exactly the source of this sound was.

In 2021, Jones hosted an “ask me anything” live stream on his YouTube channel. I was lucky enough to catch it, and the first question I asked was about this mystery amp. That’s when I first laid my eyes on the Can. It’s literally what it sounds like: a small, battery-powered practice amp built into a red plastic Jerry can. My mind was blown; I needed to know more.

“I had to take a moment to step back from the situation and admire how silly it was to be so excited about this; objectively, this amp sounds terrible, like a swarm of bees rattling around in a plastic jug.”

The story goes that SLM Electronics, an amp-manufacturing division of St. Louis Music, produced these amps in the mid ’80s as a battery-powered solution for buskers. As a novelty, they created a plastic enclosure that resembles a plastic gas can for the solid-state amplifier controls as well as the 5" speaker. Approximately 10,000 of these amps were manufactured and distributed out of the same factory where the original Crate amps were made in the U.S.

Once I learned exactly what this amp was, my mission became clear: I needed one.

I quickly discovered how difficult it is to find these amps. Even as a seasoned gear-hound, well-acquainted with the standard practice of scouring Reverb, eBay, Musician’s Friend, and every other source where used musical equipment can be found, I was coming up empty-handed. My searches resulted in a few expired Reverb listings from years earlier of people selling these amps for dirt cheap, which, while frustrating, yielded an encouraging sign that the lore behind “the Can” was not yet common knowledge. My worst fear was that word would get out about these amps and we’d end up with another instance of PDS: Peavey Decade Syndrome. (If you know, you know.)

In a turn of miraculous serendipity, I stumbled across someone selling one on Facebook Marketplace and jumped on it. I’d managed to snag my very own Can amp. I had to take a moment to step back from the situation and admire how silly it was to be so excited about this; objectively, this amp sounds terrible, like a swarm of bees rattling around in a plastic jug. However, when I finally plugged in my guitar for the first time and strummed that first D minor chord from “Exhausted,” I knew immediately: That’s the sound.

The simple truth I’ve come to terms with over the years as a guitarist is that “good tone” is purely subjective. Especially in a studio setting, some of the most iconic sounds can be uncovered in the most unconventional ways, and the Can is a true testament to that statement. While the early days of Foo Fighters were undoubtedly cast in the looming shadow of Nirvana’s massive success and catastrophic end, I think it’s finally time we recognize Grohl’s 1995 solo effort for what it is: a truly magical little slice of mid-’90s post-grunge that still packs a mighty wallop 30 years later. And in the middle of it all, this crunchy, fizzy, horrible little gas-can amp.

“There was the greatest guestlist in rock history – Jimmy Page, B.B. King, Buddy Guy, Ronnie Wood, Keith Richards, Eric Clapton and Neil Young”: Jimmy Rip was a session man in demand by Mick Jagger and Tom Verlaine – then came a rock ’n’ roll icon

“We were opening for Deep Purple, and Ritchie Blackmore got food poisoning and was in the hospital overnight”: How a support slot with Deep Purple and a last-minute guitarist replacement led to Eric Johnson meeting Christopher Cross

“They have always been a big thing for me because I think they’re the heart and soul of a Fender”: What gives a Fender guitar its spirit? For the Custom Shop's Senior Master Builder, there’s only one answer

"One of the most versatile baritone guitars I’ve ever played": Orangewood Del Sol Baritone review

“Kurt said, ‘I want the guy that did the Slayer album’”: How Kurt Cobain brought a more aggressive edge to Nevermind with the help of Slayer’s producer

“Kind of a one-trick pony”: Why Daron Malakian swears by his Friedman-modded Marshall but not the stock ones

Let it be known that Daron Malakian isn’t the biggest fan of Marshall amps, at least, not until they’ve been through the hands of amp guru Dave Friedman.

Known for crafting some of the most unmistakable tones in modern metal – from the jagged riffs of System of a Down to the layered grittiness of Scars on Broadway – the guitarist has never been content to stick with stock.

His go-to amp? A trusted Marshall, yes, but one with the custom touch of Friedman’s mods.

As Malakian’s reveals in the latest episode of Ultimate Guitar’s On the Record podcast, his tone on Scar’s new album Addicted to the Violence continues that tradition: vintage guitars, carefully sculpted layers, and amps tailored to go well beyond their original designs.

“Since the Mesmerize and Hypnotize albums, and on every Scars record, I’ve used a 1962 SG Standard that I have, and I think it’s a 1968 Gibson ES-335 that I have, and I layer those to make my heavy tone,” he says. “So I’ve stuck with that.”

“I used the same Marshall that I had on the Mesmerized and Hypnotized records and all the Scars records, but I also used Friedman’s on this, and I layered the Marshall and Friedman together.”

“Friedman actually modded that Marshall, too, so in a way, you can say they’re all Friedmans,” the guitarist adds.

Asked about the mod itself, Malakian explains: “Yeah, it’s a gain mod just to make it more chuggy and heavy. But his amps kind of have that already. I’m trying to remember the model I have, I think it’s a B.E. It’s the black one with the brown lights. So his kind of has that Marshall tone that I like out of the modded Marshall.”

What makes the Friedman amps stand out, according to Malakian, is their versatility compared to the Marshalls.

“There are just a few more options on his amps than there are on the Marshalls. The Marshall is kind of a one-trick pony,” he says.

Watch the full interview below.

Elsewhere, Daron Malakian recently reflected on System Of A Down’s 2006 hiatus, revealing he wasn’t exactly behind the idea.

“When System took the hiatus, it was difficult for me at first because that’s not really what I wanted,” he said.

The post “Kind of a one-trick pony”: Why Daron Malakian swears by his Friedman-modded Marshall but not the stock ones appeared first on Guitar.com | All Things Guitar.

“I went to Guitar Center and saw this Iceman sitting there and I was like, ‘You know, that’s a guitar that not too many people use’”: How the Ibanez Iceman became System of a Down’s Daron Malakian’s go-to guitar – and why he initially didn’t play it live

“The music was very dependent on accurate timing… If it was a big stage and we were spread out, it was just murder for us”: They were a pivotal band in prog’s golden age and split in 1980, but Gentle Giant still have a rabid fanbase

“Don’t buy it for any other reason”: The only thing to consider when buying a guitar, according to session legend Jeff “Skunk” Baxter

Jeff “Skunk” Baxter, the session ace known for his work with Steely Dan and the Doobie Brothers, thinks players are looking at the wrong things when it comes to buying a guitar.

His advice? Forget the name on the headstock, forget the price tag, and just play the damn thing until you find one that “feels good to you”.

While recently poking around a Guitar Center store, Baxter came across a $140 Squier Telecaster fitted with a Jazzmaster pickup and instantly loved how it felt. Curious, he asked to compare it to a genuine 1958 Tele hanging on the wall – a guitar priced “about a bazillion dollars” more.

“I spent about an hour setting up the Squier,” he says in the new issue of Guitarist.

“They had a guitar repair guy there and I asked if I could use his tools and set up the guitar myself. Very quickly, I compared the two, and the $140 Squier Telecaster, to me, sounded better, so I bought it.”

“It’s a great guitar,” he says.

For Baxter, the logic is simple: a guitar is only worth buying if it speaks to you. Everything else, like what it says on the headstock, is secondary.

“The first thing I would say for sure is that, if you can, ignore everything and just play it. And if it plays great, then it is great,” he explains. “Whether it’s a Squier as opposed to, like, an expensive Fender special, custom – whatever.”

“This is not to say that you shouldn’t buy quality instruments, that’s not the point. The point is that whatever guitar feels good to you is the right guitar. Don’t buy it for any other reason.”

Baxter is not alone in this. Virtuoso Joe Satriani, too, believes that players should “connect with the guitar” rather than chase after vintage instruments for the sake of it. Speaking to D’Addario, Satch admitted to being “disillusioned” with the “most valuable, rare guitars” after his youth working in a guitar shop.

“There’s nothing special about it,” he said. “The musician has to connect with the guitar for it to become special.”

The post “Don’t buy it for any other reason”: The only thing to consider when buying a guitar, according to session legend Jeff “Skunk” Baxter appeared first on Guitar.com | All Things Guitar.

“They’re like, ‘I’m in the ballpark’”: Dweezil Zappa on the “laziness” of guitar players when covering songs like Eruption

Think you can play Eruption just because you hit a few tapped notes and land in the right key? Well, Dweezil Zappa’s not buying it.

The guitarist and son of late legend Frank Zappa speaks in a new interview with Marshall, where he calls out the “laziness” of those players who, in his view, cut corners when covering songs, especially the kind that shaped generations, like Eruption.

Reflecting on his own early guitar days, Dweezil recalls how Eddie Van Halen’s visit to his home “opened up the whole world of guitar playing” for him “just by being able to see it up close”.

This was “way before YouTube”, he says, when you couldn’t just Google a tutorial or slow something down in 4K. “You had to just imagine what this stuff was, you know. Or you had to have binoculars when you go to a concert and see it up close.”

Asked if this was the reason many guitar players from that era often “came up with their own versions of things”, Dweezil doesn’t exactly agree.

“There’s a lot of people that – and sometimes it just comes down to laziness – they’re like, ‘Well, I’ll just do my own thing.’ Because they hear enough of it, and they’re like, ‘I’m in the ballpark. I’ll just make my [own thing],’” he says.

“But to me, when I was learning songs, if it was Van Halen or if it was something that Randy Rhoads was playing, I didn’t feel like I was playing the song at all unless I played exactly what I heard them doing. And I wanted to learn the nuances. I wanted to try to get the sound. I wanted to do that. Because to me, that was the whole package of playing the song.”

“So when somebody says, ‘Hey, I can play Eruption, I’m like, ‘Great! Let me see it.’ And if it’s not what I heard on the record, then to me it’s not it,” Dweezil continues. “As a kid, that was the goal: to try and get as close as I could on any of that stuff, which is not easy. It’s been a lifelong obsession to learn how to play a lot of this kind of stuff.”

Elsewhere, Dweezil also opens up about his dad’s peculiar guitar playing style, calling it “the battle between the chicken and the spider”.

“It’s not a comfortable way to play,” he says.

The post “They’re like, ‘I’m in the ballpark’”: Dweezil Zappa on the “laziness” of guitar players when covering songs like Eruption appeared first on Guitar.com | All Things Guitar.

“Guitars are like human beings – if you don’t play them, they get sick”: Why John McLaughlin doesn’t believe in collecting guitars

Jazz fusion virtuoso John McLaughlin has opened up some of the prized guitars he’s parted ways with over the years and the reason he prefers giving away guitars to collecting them.

“I think back on how many guitars I’ve given away. And I do have some regret,” the guitarist admits in a recent chat with MusicRadar.

One of those guitars was a 1963 Gibson L4-C with a Charlie Christian [Lollar] pickup, which he was forced to sell during a difficult time in his life: “It was a beautiful guitar,” says McLaughlin. “It had a great jazz tone, but I ran out of money and had to sell it to eat!”

McLaughlin ended up selling the guitar to an “angling friend”. He then tried to buy it back several months later when his finances improved, but unfortunately by then, his friend had grown too attached.

“I asked him, ‘Will you sell me the guitar back?’ He said, ‘No way, man. No way.’ So that was gone forever!”

There’s also the white 1967 Fender Stratocaster he gifted to Jeff Beck after a tour they shared in the 70s.

“I gave a 1967 white Strat to Jeff Beck after a tour we did together in 1974, or ’75,” says the musician. “And when we lost Jeff, his wife wrote to me and said, ‘I’m going to sell the guitars. They’re all around me, and they keep reminding me of him.’”

While McLaughlin attended the London auction that followed, even he couldn’t tell which white Strat had once been his.

“They had all these instruments, along with amps, pre-amps, and pedalboards. But there were two white Strats! I don’t know which of them I gave him, but anyway, I saw it there!”

Still, McLaughlin isn’t one to dwell long on what’s been lost. For him, guitars are meant to be played – and passed on when they’re no longer in use.

“I’m not a collector,” he says. “I get guitars, but I give them away.”

To McLaughlin, guitars are living, breathing companions and they’re not meant to sit on a shelf. “Guitars are like human beings – if you don’t play them, they get sick. They really need to be played.”

“Instruments are like a marriage between heaven and hell,” he continues, “They’re made on Earth, but the stuff that comes out of them is made in heaven. They’re wonderful in that way.”

The post “Guitars are like human beings – if you don’t play them, they get sick”: Why John McLaughlin doesn’t believe in collecting guitars appeared first on Guitar.com | All Things Guitar.

“From a selection of over 300 instruments I’ve measured over the past seven years, things are not quite what they seem”: Why string spacing can radically change the way an electric guitar plays

“That's my specialty: playing fast clusters of notes with the guitars. I had to pluck with four fingers instead of three!” Billy Sheehan and Paul Gilbert trade blistering licks in this standout rocker from Mr. Big

Halestorm pick their five most underrated rock and metal bands

If 2024 had ‘Brat summer’, then 2025 may well be on the cusp of ‘Halestorm summer’. When I interview frontwoman Lzzy Hale and lead guitarist Joe Hottinger at the Gibson Garage in London, the Pennsylvania hard rockers are about to enjoy several career milestones. The day after we talk, they’ll support Iron Maiden at the 75,000-capacity London Stadium, and the weekend after that they’ll perform at Ozzy Osbourne and Black Sabbath’s blockbuster farewell show. Oh, and on 8 August, they’ll release Everest: comfortably the best album of their 15-year recording career so far.

“We’re peaking right now,” Hottinger laughs when I mention the stacked schedule his band have for the coming weeks. “It’s all downhill from here.”

If Everest receives the goodwill that it deserves, then hopefully not. On their sixth full-length, Halestorm eschew the trappings of US radio rock without sacrificing their melodic punch. The songs are heavy, passionate jams with an improvisational spirit, achieved by the fact they went into the studio with producer Dave Cobb with nothing written down.

“There is a looseness to it,” Hale says. “I think – given the circumstances and the fact that we were forced to live in the moment, trust ourselves, trust our guts and make decisions – we stopped ourselves before we were getting bored with something or something was getting too comfortable. In essence, that’s what live music is all about for us anyway.”

That verve quickly appears on opener Fallen Star, when Lzzy cackles and screams “Kick it!” before she and her bandmates launch into one of the nastiest riffs of their lives. Combine that with the searing lead lines of I Gave You Everything and the lung-popping shouts during Watch Out!, and you get an album that finally captures how raucous this foursome are in the live arena.

Lzzy Hale and Joe Hottinger performing at Black Sabbath’s final concert in 2025. Image: Alison Northway

Lzzy Hale and Joe Hottinger performing at Black Sabbath’s final concert in 2025. Image: Alison Northway

On paper, Cobb seems like a wildcard pick for the producer of such an unapologetically rock’n’roll project. Though he’s produced Rival Sons and Greta Van Fleet in the past, he’s mainly known for working with such country-pop superstars as Chris Stapleton and Brandi Carlile. I ask what made him the man for the job of overseeing Everest.

“I love the Chris Stapleton record,” says Hottinger, “and Brandi Carlile is just a monster. Every time I fall in love with a record, I see his name and I’m like, ‘That fucking guy again!’”

“We’d have conversations with Dave and ask, ‘How did you make this or that work?’,” Hale adds. “He’d be like, ‘That was just the vibe on that day. We were literally living in the moment.’ For us, no matter what genre, I think that that’s just a good divining rod to be guided by.”

For all the rambunctiousness that Everest smacks the listener with, the album lyrically alternates between rock star pageantry and affecting levels of introspection. On lead single Darkness Always Wins, Hale cries, “We are fighters, holding up our lighters!”: a line almost definitely written with the intention of getting phone torches during their arena shows. Similarly, K-I-L-L-I-N-G is a barnstormer with a spell-along hook that anyone can quickly get caught up in.

On the other end of the spectrum, though, are lyrics as personal as those on Broken Doll, where Hale laments previous, toxic relationships. “I still believed the lies we shared, shattered dreams beyond repair,” she sings. Like a Woman Can is a defiant declaration of the singer/guitarist’s bisexuality, while How Will You Remember Me? finds her asking the lofty question of what her legacy will be after she dies.

“I was tired of what I had created in the past – this pedestal, the idea of me – and ready to say things that way that I actually feel them,” Hale explains. “I don’t have to have all the answers and everything doesn’t always have to be okay. I feel like, in past years, especially after fame happened and all of a sudden you’re a role model, I needed to be a beacon of hope for everybody. I wrote all these songs that said, ‘It’s gonna be okay,’ but that’s not reality. We don’t know whether everything is going to be okay.”

As Halestorm prepare to put out their best music yet and get ready for a summer that will surely only make their star burn brighter, I turn the conversations to bands who haven’t had that level of fortune and attention. Below, you’ll find Halestorm’s picks for great rock and metal bands that should have become household names but, for whatever reason, unjustly fell short of megastardom.

Halestorm. Image: Press

Halestorm. Image: Press

Sevendust

Lzzy: “They’re an incredible band, but they’ve always been notorious for, like, everybody that’s ever opened for Sevendust has gone on to do great things. They’re kind of the springboard for that. [1999 album] Home was the thing that knocked me out of my parent’s generation of music. I was listening to Judas Priest and Alice Cooper and Dio and all of that, and then Home came out, and there’s a song called Licking Cream with Skin from Skunk Anansie on it. I remember thinking, ‘Oh, girls can sing this type of music! There’s hope for me!’

“I remember meeting them: I had been a fan for a little while and then we went to the NAMM convention in the States. They had a small gig there and somebody got me in. They were the sweetest men in the world! A couple months later, they had a show in Lancaster, Pennsylvania at the Chameleon Club. They remembered us, invited us onto their bus and took our demo CD. They played one of our songs through the PA right before they went on! I remember turning to my little bro, just like, ‘Well, if Sevendust think we’re cool enough to have our song played in front of their audience, maybe we got something here.’”

Priestess

Joe: “They’re a band from the very early 2000s that never got too huge. They did some touring and I think they made two records. I still love that band. They have a record called Hello Master and I found a vinyl of it, an original pressing, at a shop in Nashville for like 20 bucks. It melted my brain! How they started that record is some of the inspiration for how we started this new record, because it’s just a killer riff that goes on for too long. Haha! It’s in a different time signature and I was like, ‘That’s brilliant!’ It was one of my favourite records coming up.”

The Divinyls

Lzzy: “They’re an overlooked punk band that were only ever known for [1990 single] I Touch Myself, and the rest of their albums sound nothing like that. They’re this crazy, high-energy Police-meets-old-school-punk kind of band. Nobody ever really digs deeper than that one hit they ever had.

“I got into them kind of by accident. I realised later, ‘Oh, they’re the I Touch Myself band.’ The lead singer [Chrissy Amphlett] ended up dying many years ago, but they were one of those bands that opened up for everybody and then never really got their due, except for that one song. It was completely unhinged, amazing vocal prowess. The guitars were really interesting. You could tell that they were very jazz-influenced, but then they all got into punk bands when they were teenagers.”

Killing Joke

Joe: “The record that got me into them was the one Dave Grohl was on [2003’s Killing Joke]. That got me into Killing Joke, that was my introduction. Don’t they have a songwriting credit on Come as You Are or something? [Nirvana’s riff was strikingly similar to the one in 1984 single Eighties. Killing Joke were reportedly annoyed about it, but didn’t take legal action – Legal Clarification Ed]

“I discovered them through that record because it was on a random playlist or something, and I heard it and I was thinking, ‘That sounds like fucking Dave Grohl – what are we listening to?!’ Then I went deeper and deeper and I bought the record. It was just on for, like, a year and a half straight.”

Lzzy: “I’m definitely a fan. It’s just the energy of a song like Asteroid and the personality. There are certain people who are able to exude that kind of energy vocally where you get to know who they are. You’re just like, ‘Man, I know everything about you just from that run!’”

Mrnorth

Joe: “They were Irish boys and they made a record on a big label [2004 debut album Lifesize was released by RCA]. I think they did some pretty good touring. The vocals were soaring, like Jeff Buckley, but they were a rock band. Lifesize is a beautiful record. They had a shot, I guess, but it didn’t quite go their way. We’d see them play all the time at Grape Street pub in Philadelphia. They were so good live!”

Lzzy: “Their lyrics were pure poetry. They took you to a different place. The words were like visuals. He [singer/guitarist Colin Smith] had a way of taking his surroundings – there was a lot of talk about trees and nature – but then relating them to one’s inner self. I remember thinking, ‘How do people think that way?!’”

The post Halestorm pick their five most underrated rock and metal bands appeared first on Guitar.com | All Things Guitar.

This Will Destroy You Rig Rundown

The doomgaze titans from Texas hit the road this year to celebrate more than two decades together, and they brought some of their favorite noisemakers for the occasion.

Post-rock/doomgaze outfit This Will Destroy You, formed in San Marcos, Texas, in 2004, are marking 21 years together, and 20 years of their self-recorded debut Young Mountain, with an anniversary tour. In late June, the band played Nashville’s Basement East, where guitarists Jeremy Galindo and Nicholas Huft and bassist Ethan Billips met up with PG’s Chris Kies to share what gear they packed for the roadtrip.

Brought to you by D’Addario

Trusty Tele

Galindo started off playing electric on his brother’s Fender Telecaster, and he’s never looked back. He’s played various models over the years, but got this Fender American Performer Telecaster two years ago. He strings it with .011–.052 strings for slightly more body and fullness, and tunes it to E-flat standard. Galindo mostly plays with his fingers, but when he picks he uses some of the thinnest picks he can find.

No Tubes? No Problems

A Music Man HD-130 is Galindo’s always-and-forever, but on the road, he likes this Roland Jazz Chorus 120 for its tubeless reliability and easy clean sounds.

Jeremy Galindo’s Pedalboard

The Boss DD-20 Giga Delay and Tech 21 Boost R.V.B. have been with Galindo since the early days, and he considers the Tech 21 to be the most essential tool of his kit. Aside from those, there’s a Walrus Canvas Tuner, Ernie Ball VP JR, Friday Club Fury 6-Six, Walrus Jupiter, Walrus Fundamental Ambient, Boss RE-20, and Mr. Black Deluxe Plus. A Walrus Aetos powers the party.

Smooth as Sandpaper

This Fender Jazzmaster, Huft’s first, was bought from Full of Hell guitarist Spencer Hazard, who equipped it with its “awful sandpaper texture” finish. Huft doesn’t use the rhythm circuit, so he’s taped it off. He plays with both pickups engaged at all times, including the humbucker rail pickup in the bridge.

United Solid-States

Huft has a soft spot for 1970s solid-state amplification, which makes this Peavey Standard Mark III series a perfect match for TWDY: It’s cheap, and it’s loud.

Nicholas Huft’s Pedalboard

Along with an ABY switcher, Huft runs a Boss TU-3, Ernie Ball VP JR, Gremlin Machine Shop Worshiper, Dead Air Portrayal of Guilt/Matt King Dual Drive, Boss DD-200, Boss RC-500, Red Panda Context, Boss DD-3T, Beautiful Noise Exploder, and Walrus Slo.

Cheap and Cheerful

Billips explains that he and his bandmates grew up on cheap instruments, and they still feel like home, so that’s why he rocks with this Marcus Miller Sire bass.

Community Cranker

Billips and his bandmates split on this Darkglass Electronics Microtubes 500 v2 head, which they share collectively.

Ethan Billips’ Pedalboard

Billips runs an Ernie Ball VP JR Tuner, a prototype bass overdrive from Mr. Black, a Death by Audio Bass War, Walrus Badwater, Danelectro Talk Back, Catalinbread Topanga, and a Radial BigShot ABY.

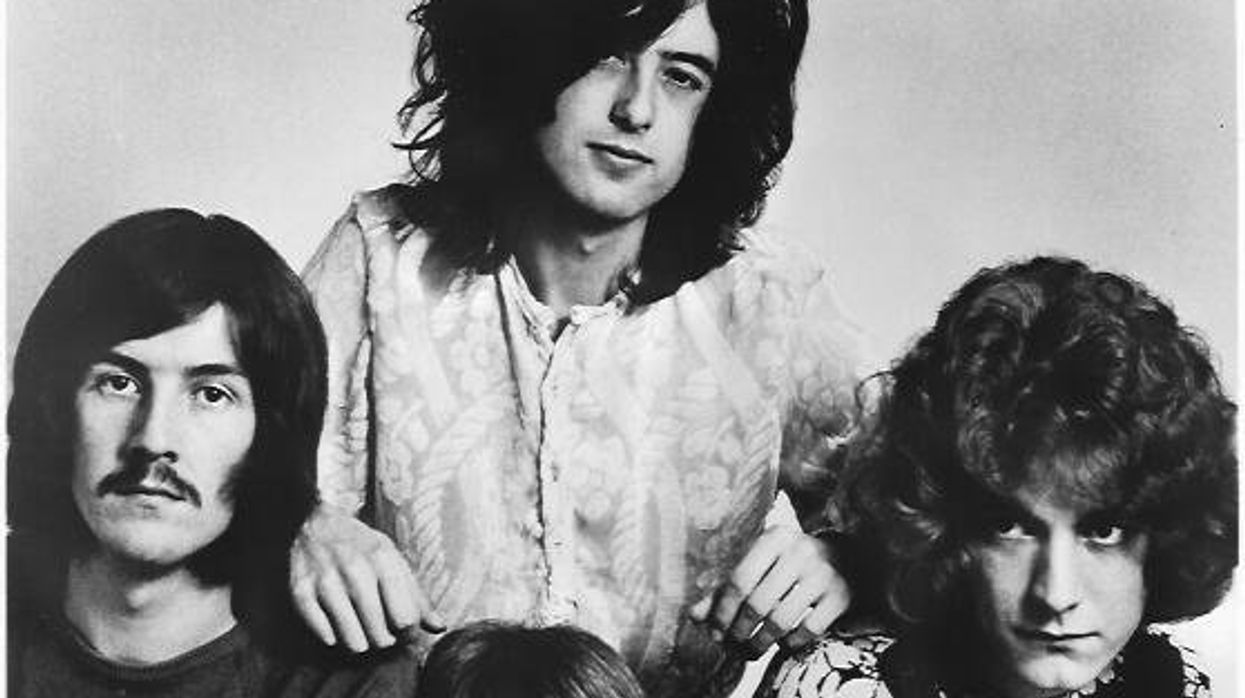

Be More Like Led Zeppelin

Making great music requires pushing the envelope, not pushing buttons.

As a teen, I signed over my soul to the Columbia House mail-order mafia and bought the first few Led Zeppelin albums. I wore those albums out, dropping the needle in front of the “Heartbreaker” solo, “Black Dog,” and “Stairway” daily. Eventually I moved on to other obsessions and forgot how amazing this band was—until last night, when I watched Becoming Led Zeppelin, Bernard MacMahon’s 2025 documentary. The film, which earned a 10-minute ovation at the Venice Film Festival and grossed $13.2-million by May 2025, charts the explosive rise of Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, John Paul Jones, and John Bonham from their 1968 formation to 1970’s global dominance.

Although Page and Jones had worked together as session musicians, the first time the Zep lineup played music together was a jam in a tiny, rented rehearsal room in 1968. They tested their collective sound, starting with blues standards like “Train Kept A-Rollin’” and “Smokestack Lightning.” Forty-four days later, they were recording their first album, which they completed in 36 studio hours. This raw fusion of blues, rock, and psychedelic chaos, using a 4-track recorder and a shoestring budget of £1,800 (about $4,300, then), helped usher along a paradigm shift in music. Tracks like “Dazed and Confused” and “Good Times Bad Times” took wild risks, blending modal riffs, orchestral swells, and improvisational fire. Led Zeppelin was also incredibly diverse, with the heavy blues balanced by the acoustic “Black Mountain Side,” which was inspired by folk and Indian music. Zep II pushed further, from the primal riff of “Whole Lotta Love” to the semi-pastoral “Ramble On.” Page’s violin bow on guitar and Bonham’s heavier-than-heavy drumming defied norms, while Plant’s primal vocals careened between octaves.

Most of today’s modern music is polished to predictability, sterilized, and quantized. I bet that 99 percent of the sessions I’ve played on over the past two decades were all built on a grid with a stagnant click. Zep’s approach to tempos is more like classical music, where the tempo follows the emotion. “Dazed and Confused” starts with a slow, brooding tempo (around 60 to 70 bpm) driven by a descending bassline and Page’s eerie guitar. The middle section accelerates into a frenetic jam (around 120 to 140 bpm), with Bonham’s aggressive drumming and Page’s wild soloing, before slowing back down for the haunting violin-bow section and a final explosive ramp-up to 140 bpm. On “Babe I’m Gonna Leave You,” the transitions are so abrupt it feels like a car ran a red light and hit your passenger door. Zep would have been boring if they were constrained by a click.“If ‘Stairway to Heaven’ debuted today, would anybody hear it?”

Zeppelin’s tones and timbres also kept it unpredictable and endlessly interesting. Although John Paul Jones’ ’62 Jazz bass, Bonham’s Ludwig Super Classic, and Page’s guitars did most of the heavy lifting, Zep gave us vast sonic variety. Between the four members, they played 15 instruments on their first three albums and went to great lengths to make every song its own, unique sound. Yet, regardless of the instrumentation, Zeppelin always sounds like Zeppelin.

Rock ’n’ roll was built on experimentation and rebellion. It’s truly a DIY genre. So how did modern rock become so homogeneous and tame? Today’s unlimited digital tracks and AI tools (used in 60 percent of 2024’s Top 40, according to MusicTech.com) encourage overproduction, smoothing all quirks along the way. Radio and streaming exacerbate this as labels push 3-minute singles with hooks in 30 seconds to fit ad-heavy radio and prevent Spotify skips. Zeppelin’s era had FM stations playing 7-minute epics. Today, labels prioritize safe bets, favoring formulaic hits over risks. Social media and streaming reward conformity—songs must grab instantly, not unfold like a movie. If “Stairway to Heaven” debuted today, would anybody hear it?

By comparison, the 1960s were an incredibly open-minded time. Labels were looking for something to take a chance on because the outliers were paying off. The Beatles, Bob Dylan, and Hendrix successfully took chances, which enabled others like Zep to push the envelope farther, paving the way for yet more experimental artists like Bowie and Van Halen. The last boundary stretcher was probably Nirvana. That was 34 years ago.

There’s tons of amazing music being made today. But there’s also a whole lot of trend following rather than trend setting. Now that AI is writing/producing/creating music, that’s not going to diversify the mainstream. Becoming Led Zeppelin reminds us that music thrives on urgency and daring. Take chances.